Founded in 1950, Thomas University is a private, nonprofit institution in Thomasville that offers associate’s, bachelor’s, and master’s degrees. Most of its students are from south Georgia and north Florida. The university welcomes a student body that is diverse in age, ethnicity, religious belief, socioeconomic status, and academic preparation.

Founding

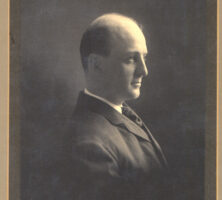

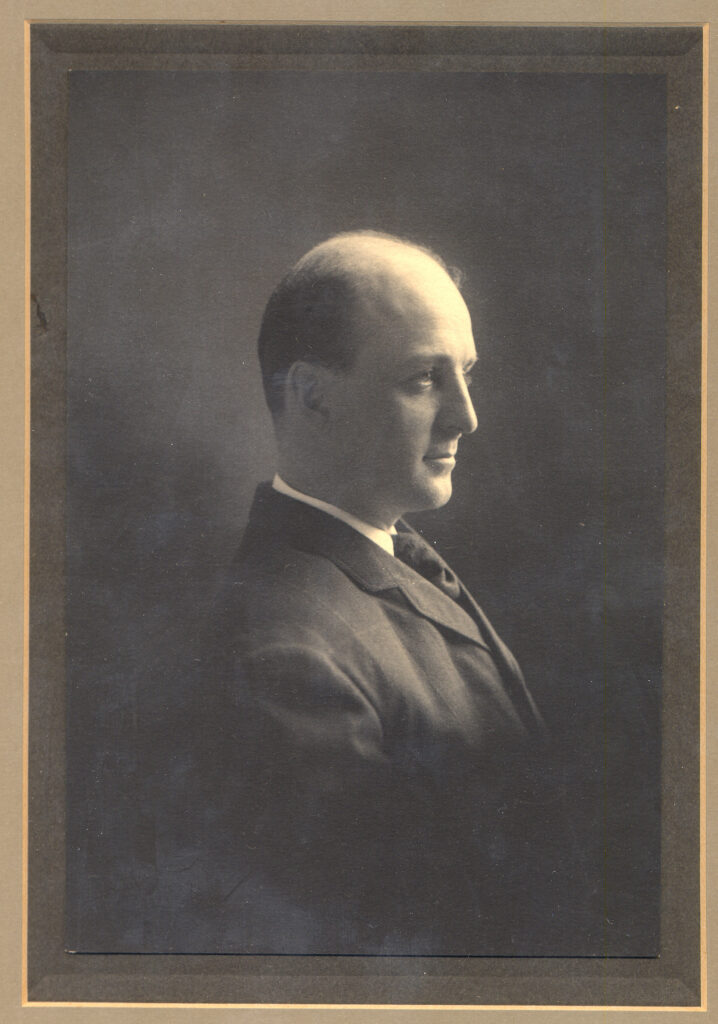

The school was founded by Primitive Baptists dedicated to providing higher education opportunities for young men and women in Georgia, Florida, and Alabama. Its founder, Elder J. Harley Chapman of Valdosta, envisioned an “undertaking without precedent in the Primitive Baptist denomination” that would ultimately provide both associate’s degrees in liberal arts and bachelor’s degrees to students “of good moral character irrespective of their religious belief.” The college was originally designed to serve 100 students, who would receive an education in the liberal arts within a conservative Christian context.

Courtesy of Thomas University

A donation of $10,000 from Mrs. Vicey Harris of Jacksonville, Florida, provided the seed money necessary to search for a suitable location for the new school. After approaching officials in Macon, Waycross, Columbus, and Thomasville, committee members ultimately decided to purchase Birdwood Plantation, just outside Thomasville, in Thomas County.

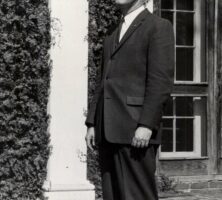

Built as a winter resort in 1932 by W. Cameron Forbes, U.S. ambassador to Japan and one-time governor of the Philippines, Birdwood Plantation contained a main house (which still serves as the university’s main administration building) and a few outbuildings on forty-eight and a half acres of land adjacent to Glen Arven Country Club.

Courtesy of Thomas University

In 1950, with the school’s name—Birdwood College—chosen and a location secured, the executive committee attempted to recruit the college’s first entering class, with little success. The original fall 1951 opening date was postponed. After a new board of trustees was installed in 1953, a dedicated campaign ensued to “Open the Door in ’54.”

Early Years

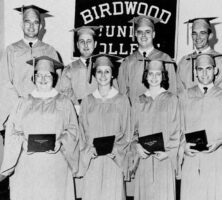

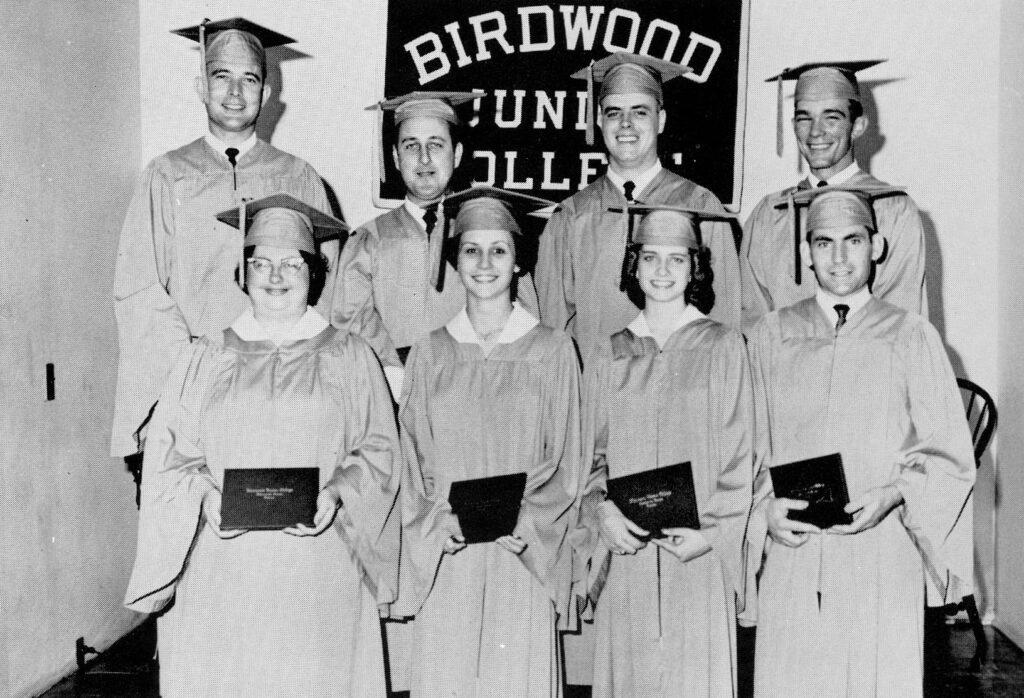

Classes began in the fall of 1954 with nine students enrolled. The financial struggles of Birdwood College increased as anticipated support from Primitive Baptist congregations failed to materialize. Lack of adequate physical facilities impeded the college’s ability to apply for accreditation, and lack of accreditation limited the number of students willing to enroll. In the fall of 1966 the board decided to stop admitting residential students, citing the additional costs of repair and remodeling of the dormitory facilities.

Courtesy of Thomas University

During its first twenty years, Birdwood College graduated an average of 14 students a year with diplomas in liberal arts. The hoped-for 100 students never materialized, and in 1973 the college had only 56 students. Serious disagreements between factions of the Primitive Baptist Church over the role of the college contributed to the denomination’s declining support in the 1960s. Although Chapman had insisted in 1950 that the college was not intended to be a seminary to train preachers, that “God alone calls and educates men for his ministry by the Holy Spirit,” many Primitive Baptists expressed concern that Birdwood had been established to produce “intellectual preachers” who lacked the necessary divine calling the denomination demanded of its ministers. “Progressive” and “Old Line” Primitive Baptists were deeply divided over the need for youth camps, formal Sunday school curricula, and a college in their denomination.

During these years, Birdwood lacked sufficient financial resources to expand its focus. It was criticized for a lack of sufficient administrative personnel and for infrequent communication between the college and the denominational congregations. In the 1960s the board was expanded to include interested members of the Thomasville community from outside the denomination. In January 1966 the college applied for federal funds, an act that was unpopular among most Primitive Baptist churches in the region. In addition to federal funding, the resolution of the board to admit students “based on character and ability to do college work, regardless of color, race or creed” hastened the break between the college and the denomination. In 1966 the board forced Chapman to resign as president and dean.

Courtesy of Thomas University

Transition to Nonsectarian Status

Community attitudes toward the college were mixed. A local bond issue proposed in 1973 for a state junior college in Thomasville was narrowly defeated, and the intense campaign over the bond issue generated strong public debate about Birdwood Collegeand its role in the Thomasville community. An editorial published in the Thomasville Times-Enterprise that year noted several reasons that many in the community did not support Birdwood, including its sponsorship by the Primitive Baptist Church, its lack of accreditation, and the limited number of teachers and courses available.

Courtesy of Thomas University

Dwindling support from the Primitive Baptist churches in the region ultimately led to a resolution by the Birdwood College board to become a nonsectarian institution. In 1977 the name of the college was changed to Thomas County Community College. In 1979 the college officially severed relations with the Primitive Baptist denomination and became completely nonsectarian, private, and independent.

Accreditation and Growth

Once the college severed its ties to the Primitive Baptists, efforts began in earnest to secure accreditation by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (SACS). In 1984 the institution received initial accreditation by SACS as an associate-degree-granting institution, followed in 1990 by recognition as a baccalaureate-degree-granting institution. The name of the institution was changed once again, in 1986, to Thomas College.

Courtesy of Thomas University

Accreditation by SACS and the attainment of baccalaureate status contributed to a period of rapid growth. The student body grew from 369 in 1990 to more than 800 students in 1996. During the 1990s several new buildings were constructed or relocated to the Thomas College campus.

The conversion from the quarter system to the semester system, coupled with the state legislature’s more stringent requirements regarding HOPE scholarships, led to enrollment declines in the late 1990s. During this period two master’s degree programs, a master of business administration and a master of science in rehabilitation counseling, were developed. In 1998 the institution was recognized by SACS as a master’s-degree-granting institution and in 2000 changed its name to Thomas University.

In 2001 Thomas University purchased a small residence hall two miles from the main campus. Around the time of the name change it began an intercollegiate athletics program, playing as part of the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA). In 2004 the Thomas University women’s softball team won the NAIA national championship.

Since 2000 Thomas University has expanded its graduate offerings to include master’s programs in education, community counseling, and nursing. Still primarily a commuter campus, approximately half of its students are older than the traditional college student. Thomas University continues to provide postsecondary opportunities focused on preparing local citizens to serve the region.