Located on former industrial sites, brownfields are abandoned properties that are contaminated, or potentially contaminated, with hazardous pollutants.

An estimated 450,000 brownfields exist in the United States. Land developers often view such properties as being too difficult to clean up, causing them to sit as unproductive and polluted plots of land. However, qualified entities can apply to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for funding to assess and clean up brownfields in preparation for new development projects on the land. The Georgia Environmental Protection Division maintains a “Georgia Brownfield Properties” list, which tracks the fate of brownfields within the state and shows the dates of their planned cleanup.

The EPA defines a brownfield as “real property, the expansion, redevelopment, or reuse of which may be complicated by the presence or potential presence of a hazardous substance, pollutant, or contaminant and includes land contaminated by petroleum or petroleum products… or mine-scarred land.” Thus, a brownfield is not necessarily a contaminated property. It has, however, been targeted for revitalization. Individual states often have slightly differing definitions of what constitutes a brownfield. Georgia’s definition is not as explicit as the EPA’s definition, but under the state’s Hazardous Site Reuse and Redevelopment Act a property can only be considered for brownfield status once a hazardous substance has been identified through sampling of the soil or water at the site.

Some properties cannot be considered for brownfield status under either state or federal definitions. These properties include sites on the National Priorities List (also known as federal Superfund sites), sites that are involved in lawsuits or debt battles, sites that are currently undergoing cleanup, and sites that have hazardous-waste-disposal permits. Properties listed on Georgia’s state Superfund list, however, may qualify for the status of brownfield.

Goals of the EPA Brownfields Program

Because brownfields are unsightly and frequently contaminated with hazardous pollutants, they are generally dangerous to human health and often negatively affect the surrounding communities by contributing to neighborhood decay. The EPA enacted its Brownfields Program in 1995 to counter these negative effects.

The EPA Brownfields Program provides funds for the initial evaluation, cleanup, and job training necessary to safely and effectively deal with contaminated properties. In doing so, the EPA aims to encourage states and communities to safely reuse brownfields. The major goals of the program include protecting human and environmental health, revitalizing the neighborhoods surrounding a brownfield, reducing urban sprawl by utilizing all available property instead of developing new land, and boosting the surrounding area’s economy by returning land to productive use.

In the United States eight types of groups are qualified to apply for brownfield funding: state governments; local governments; quasi-governmental groups or organizations, such as land clearance authorities, that are controlled or supervised by the local government; governmental groups created by the state; any council or group working under the local government; a state-chartered agency; Indian tribes other than those located in Alaska; and Alaskan tribes that meet certain requirements. To receive funding for cleaning up a brownfield site, groups meeting the eligibility requirements must submit grant proposals to the EPA.

Rehabilitated Brownfields in Georgia

As of 2009 more than 250 properties were named on the Georgia Brownfield Properties list. Many former brownfields, including Atlantic Station, a mixed-use development project in Atlanta, and the Georgia Sea Turtle Center on Jekyll Island, have been successfully rehabilitated. The revitalization of such brownfields shows that contaminated lands can be cleaned and reused in productive ways.

Atlantic Station

Covering 138 acres on Atlanta’s west side, Atlantic Station represents one of the most successful brownfield-reclamation projects in Georgia. As of 2009 Atlantic Station was the largest urban brownfield project in the country, and it includes the Southeast’s first office building to be certified by Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED), a status granted to buildings that meet strict energy-efficiency requirements. LEED-certified buildings use, on average, 25 to 30 percent less energy than a standard building.

Courtesy of Atlantic Station

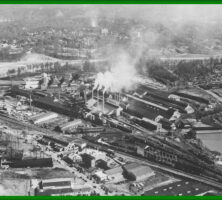

The Atlantic Steel Mill previously occupied the Atlantic Station site. The mill was in operation for more than 100 years before closing in December 1998. The manufacturing of steel over the course of so many years left the soil and groundwater on the property highly contaminated. Jacoby Development purchased the property with the intent of developing commercial, residential, and recreational buildings with “green” (environmentally friendly) principles in mind. Developers spent approximately $10 million in cleaning the site, and more than 12,000 truckloads of materials were removed. The cleaned site reopened as Atlantic Station in December 2001.

Today Atlantic Station, a New Urbanist development, is one of the most environmentally sound development complexes in the Southeast. It provides housing for 10,000 people who work nearby, and its proximity to a MARTA station encourages the use of public transportation.

Jekyll Island

Jekyll Island is a barrier island along the Georgia coast managed by the Jekyll Island Authority, an organization that oversees preservation of the island’s natural resources, including its live oak trees, Spanish moss, and abundance of wildlife. The island is home to the Georgia Sea Turtle Center, which provides medical treatment for injured sea turtles and conducts research and educational programs on sea turtle conservation.

Courtesy of Georgia Sea Turtle Center

Established in 2007, the Sea Turtle Center stands on property that was previously home to a coal-fired power plant. Though the power plant has long been shut down, the property was suspected of being contaminated with the industrial toxins lead, mercury, chromium, and battery-acid drainage. The EPA awarded $80,000 to the Jekyll Island Authority for investigations into property contamination and for the subsequent cleanup that turned this hazardous site into an educational facility.