The Atlanta Negro Voters League (ANVL) was a bipartisan political organization started by Black leaders in 1949 to form a united front to maximize the strength of the Black vote. Such an organization was needed because of the surge in Black voter registration after a 1946 federal court ruling invalidated Georgia’s all-white primary. By 1949 African Americans represented at least 25 percent of Atlanta’s registered voters. Founded on July 7, 1949, at the Butler Street YMCA, the league served as a clearinghouse for Black problems and as broker for the African American vote until the early 1960s.

Structure

The ANVL was set up on a nonpartisan basis to make sure that Black Republicans and Democrats worked together in selecting desirable candidates for city and county elections. Although Blacks did not constitute a large enough part of the population to elect African Americans to office, they could and did join forces with moderate whites to keep racist whites out of city hall. The league made no endorsements in state and national elections.

Organized in a spirit of bipartisanship, the ANVL created dual chairs to ensure equality between the two political parties. John Wesley Dobbs, retired postal employee and leader of the Prince Hall Masons of Georgia and the Fulton County Republican Club, and attorney A. T. Walden, president of the Atlanta branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and leader of the Fulton County Citizens Democratic Club, served as the first cochairs of the executive committee. The chairs appointed all committees as well as the twenty-five members of the executive committee, which served as the policymaking board of the organization. The general committee was composed of prominent Black civic, religious, and business leaders.

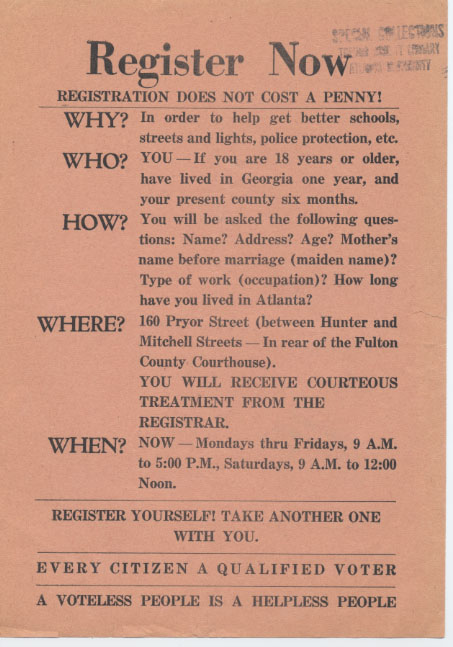

The two most important committees of the ANVL were the registration committee, which registered and organized campaign workers to assist Blacks in their efforts to register to vote, and the screening committee, which acted as the brokerage house for the Black vote with individual white candidates. Through the screening committee Black leaders put forward their concerns and demands to white politicians in the hope of finding a candidate who was sympathetic to their needs.

The ANVL helped register African Americans to vote, educated those voters on election procedures, and got them to the polls on election day to vote for candidates selected by the screening committee. The league was a grassroots movement that held public meetings in various sections of the city and invited candidates to meet the Black community. The league’s endorsement of candidates was done in secret so as not to prejudice the white population against any candidate.

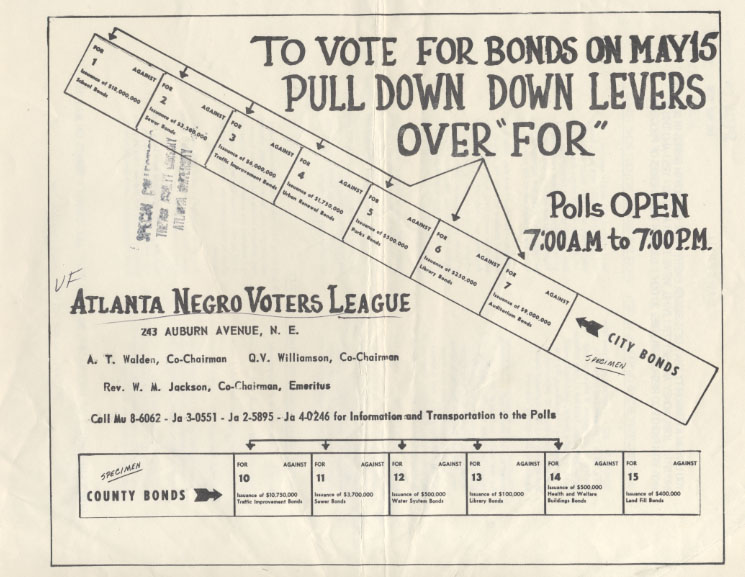

Before each election the ANVL mailed postcards to all the city’s Black registered voters to inform them about the program and their respective ward leaders. Two nights before election day, the ANVL released a ticket with its slate of candidates and instructions on how to operate a mechanical voting machine. The ticket was also published in the Atlanta Daily World, a Black newspaper, and announced over WERD, the city’s first Black radio station. Black ministers assisted in the effort, using their pulpits to rally African Americans to support candidates endorsed by the league. To make sure that Blacks participated in the electoral process, carpools were organized and taxis provided to carry voters to the polls.

The Biracial Coalition

The 1949 primary marked the emergence of a biracial coalition of African Americans and moderate whites that successfully supported progressive mayoral candidates throughout two decades. The ANVL endorsed William B. Hartsfield in his reelection bid for mayor. The Black vote provided the margin of victory for Hartsfield in 1949, 1953, and 1957. In 1961 Blacks also helped Ivan Allen Jr. win his first contest for mayor.

From 1949 to 1953 the ANVL acted primarily to endorse white candidates. The league delivered Black votes in exchange for modest benefits from the white moderates the ANVL had helped to elect. The African American community received such political rewards as new and improved lights, streets, garbage collections, sidewalks, and school buildings. Blacks were hired as policemen, although they were stationed in a segregated unit and could not arrest whites. Treatment of Black citizens by city officials was improved, and discriminatory courtroom treatment was minimized.

In 1953 the ANVL transformed itself from an endorsing organization to one that recruited Black candidates for elections. That year Rufus Clement, president of Atlanta University (later Clark Atlanta University) and a league candidate, with the help of white moderates defeated a white incumbent on the Atlanta Board of Education. A. T. Walden and Miles G. Amos, a Black pharmacist, won seats on the city Democratic executive committee, thus giving Blacks a voice in municipal politics.

Although Walden worked hard to develop a united Black voting block, his efforts suffered a severe blow in the 1953 mayoral primary. Dobbs, upset that no Black firemen had been hired, split with the ANVL and withdrew his Republican supporters from the league. The following year he was replaced by the Reverend William Jackson of Bethlehem Baptist Church. Jackson remained cochair until 1961, when he was succeeded by Q. V. Williamson.

The activities of the civil rights movement in Atlanta in the early 1960s caused a disruption in Black leadership and the emergence of a new group of leaders who had no allegiance to the ANVL. Weakened by lack of leadership and by Walden’s death in 1965, the league ceased to be a significant political force in Atlanta.