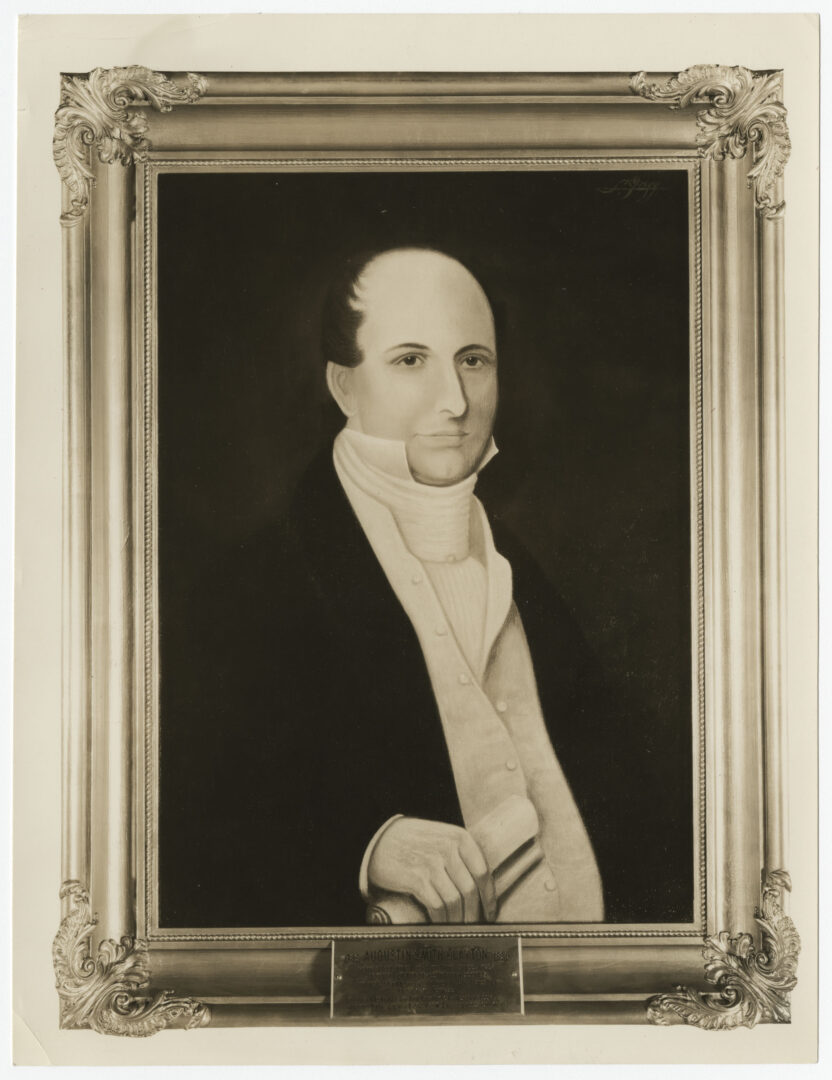

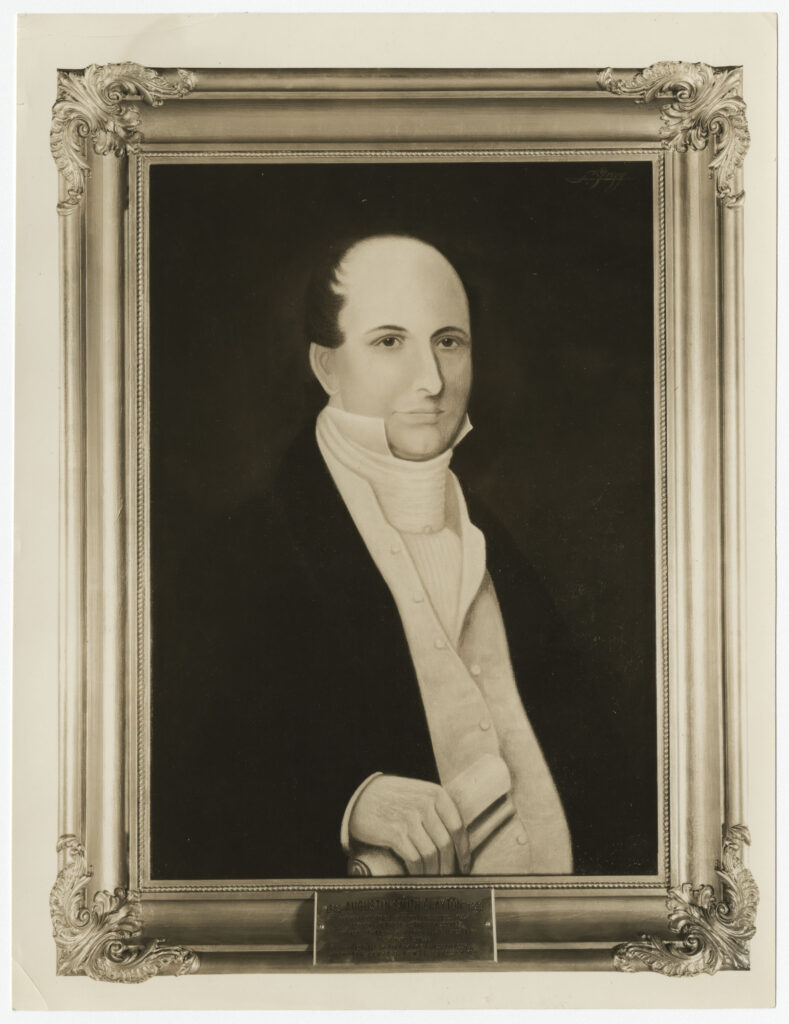

Augustin Smith Clayton was a politician and jurist of national significance in the early nineteenth century. Both Clayton County and the town of Clayton, the seat of Rabun County, are named in his honor, as are major streets in Athens and Lawrenceville.

Clayton first gained national prominence in the late 1820s while serving as the judge of original jurisdiction over the cases leading to the removal of the Cherokee Indians from Georgia. Shortly thereafter he served as Georgia’s leading advocate of nullification. As a U.S. congressman in the early 1830s he led the attack on the Second Bank of the United States, during U.S. president Andrew Jackson’s so-called Bank War.

Early Life and Education

Clayton was born in Frederick County, Virginia, on November 27, 1783, to Mildred Dixon and Philip Clayton. Soon after his birth, the Clayton family moved to Augusta, Georgia. Although a tradesman, Philip Clayton provided a dowry for his daughter and an education for his sons. The young Clayton attended the Richmond Academy in Augusta, where in May 1791, at the age of seven, he so impressed visiting U.S. president George Washington with his orations that Washington awarded him an inscribed book. William Harris Crawford, who later became a prominent politician in the state, reputedly tutored Clayton at Richmond Academy.

In 1801 Clayton enrolled at the University of Georgia in Athens, where he helped found the Demosthenian Society and served as the class poet for Franklin College’s first graduating class, in 1804. Clayton considered the University of Georgia to be an integral part of his life, and he remained committed to it and to the Demosthenian Society for the rest of his life. He became treasurer to the Senatus Academicus, the body charged with overseeing the affairs of the university, in 1808 and was elected secretary of that body in 1812.

Early Legal Career

Following graduation, Clayton read law under Judge Thomas P. Carnes. He gained admittance to the bar in 1806 and then practiced law briefly in Carnesville. Clayton married his mentor’s niece, Julia Carnes, in 1807, and moved his family back to Athens, which served as his home for the rest of his life. Two of his sons, Philip Clayton and George R. Clayton, later became important politicians in their own right. A granddaughter, Julia C. King, married the prominent journalist Henry W. Grady. Whenever not actively engaged in public service, Clayton practiced law and managed his agricultural and business pursuits. His family claimed that he gained wealth through his diligence in practicing law, and he paid taxes on sufficient property in land and enslaved people to be counted a planter by 1820.

Like many aspiring lawyers, Clayton both rode the legal circuit and entered into politics. He served as a Clarke County representative to the General Assembly from 1810 to 1812, and as clerk of the House of Representatives from 1813 to 1815. Growing from his duties as clerk, Clayton published several legal treatises, the first compiling Georgia’s laws of the previous decade and the second explaining the duties of the justice of the peace in Georgia. In 1815 Athens elected him to the town commission, and he served for two years. In 1819 the state legislature elected him judge of the western circuit. He served in that capacity until 1825, and then again from 1827 to 1831. Between stints as a judge, Clarke County elected him to the state senate, where he chaired the internal improvements committee. During the early 1820s, Eugenius A. Nisbet, who was elected in 1845 as one of the original justices on the Supreme Court of Georgia, studied law in Clayton’s Athens office.

Indian Removal

In the 1820s Clayton became one of the most outspoken proponents of Indian removal in Georgia. Writing under the pen name “Atticus,” Clayton published a series of essays advocating acceptance of the controversial Treaty of Indian Springs, signed by Creek leader William McIntosh in 1825. The treaty eliminated the Creek Nation’s claims to large portions of the state. In short, Clayton claimed that Native Americans possessed no legal title to their lands and that they lost the temporary right of occupation if they were not actively using the land. He further argued that the national government had no right to interfere with the treaty, which was an internal affair of Georgia.

Following the Cherokee Nation’s adoption of a written constitution in 1827, Clayton presided over the cases in which the state of Georgia and the Cherokee Nation argued over the right to make laws for Cherokee land within the state. The earliest cases established that Georgia would extend its laws over the Cherokees and ignore interference from the federal government. In Georgia v. Saunders (1830), Clayton’s court ruled that Cherokee law enforcement lacked the authority to arrest, try, and punish a white man for stealing a horse near Ellijay, deep in the Cherokee Nation. TheGainesville jury for that case convicted thirteen Cherokee officials of false imprisonment and of assault and battery. In Georgia v. Tassels (1830), another jury in Gainesville convicted a Cherokee, Corn Tassels, of murdering another Cherokee near Etowah in the Cherokee Nation. The U.S. Supreme Court issued a stay of execution, but Georgia governor George R. Gilmer and the state legislature refused to deliver the stay to Clayton, and Tassels was hanged on December 24, 1830.

Clayton’s most important Cherokee case, State v. Missionaries, involved Georgia’s requirement that all whites in the Cherokee Nation obtain a passport, which demanded swearing allegianceto Georgia’s laws. State authorities arrested white missionaries in March 1831 for violation of the passport law and brought them to trial at Clayton’s court in Lawrenceville. Clayton sentenced the missionaries to four years imprisonment. The missionaries appealed the case, and in 1832 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against Georgia in Worcester v. Georgia. However, the federal government under President Andrew Jackson refused to enforce the ruling, which ultimately led to the removal of the Cherokees in 1838-39.

In the September 1831 term of the Gwinnett Superior Court, Clayton ruled that Georgia’s law prohibiting the Cherokees from mining gold was unconstitutional. Governor Gilmer disagreed and ordered the state militia to ignore Clayton’s ruling and to stop all Cherokee mining. Two months later, Clayton lost his seat on the bench when his own Troup Party, a faction led by George Troup, perceived him as being too evenhanded with the Cherokees and refused to reelect him as judge. Clayton’s stand on states’ rights, however, led the party to choose him as its candidate for a special election in December 1831. The election was held to fill the U.S. congressional seat vacated by Wilson Lumpkin upon his election as Georgia’s new governor.

The Bank War and Nullification

In February 1832 Clayton took his seat in Congress and quickly became a chief opponent to the perceived power of the Second Bank of the United States. In March 1832 he called for an investigation of the books of the bank, and in early May a committee, including himself and former U.S. president John Quincy Adams, traveled to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Clayton, as chair, wrote the committee’s report denouncing the bank for violating the provisions of its charter, while Adams issued a minority report arguing that the bank operated completely within the law. That same month, Clayton served as a delegate to, and was elected a vice president of, the convention that nominated Martin Van Buren as Jackson’s vice presidential candidate for the 1832 election. With the passage of a revised tariff in June 1832, however, Clayton broke with Jackson and joined John C. Calhoun in expounding the doctrine of nullification.

Nullification theorized that each state possessed the authority to rule a federal law unconstitutional within its own boundaries, thus requiring the federal government to negotiate with the states over the implementation of federal laws. Clayton had originally advocated nullification in response to the federal government’s failure to remove Native Americans from their ancestral grounds in Georgia, but he had become Georgia’s fieriest nullifier with the passage in 1828 of a tariff that increased taxes on imports to as much as 100 percent of the goods’ values. In response, Clayton constructed the state’s first cotton factory, the Georgia Factory, near Athens in 1829 to demonstrate how unnecessary the protective tariff was. After doubling his investment in two years, Clayton debated tariff reform on the floor of the House with the North’s foremost industrialist, Nathan Appleton.

After the tariff was revised in 1832, Clayton and attorney John Macpherson Berrien called a meeting in Athens to organize a statewide convention that would seek to nullify it. Around this time, Clayton reportedly made statements in South Carolina supporting that state’s opposition to the federal government. He specifically claimed that when southern interests and rights were in danger, “he that dallies is a dastard, and he that doubts is damned.” The profanity of those words would come back to haunt him.

Clayton continued to work for Georgia’s economic independence in the 1830s by helping to organize the Georgia Railroad and by calling for southerners to engage indirect trade with Europe, cutting out middlemen in their business.

Jacksonian Politics

Clayton broke with Jackson over the nullification crisis and over the president’s removal of the national deposits from the Second Bank of the United States. In each case, he came to see the president as someone who ignored the Constitution. Removal of the deposits without authority from Congress seemed to usurp Congress’s constitutional authority. Similarly, Jackson’s executive order in December 1832, which threatened to use force against South Carolina if that state continued to arrest federal employees for carrying out their duties, struck Clayton as a violation of states’ rights. Clayton had come to see Jackson as a tyrant—”King Andrew,” as his opponents called him.

As a result of his opposition to Jackson, Clayton changed his allegiance from Jackson’s Democratic Party to the anti-Jackson Whig Party. In 1833 he organized Georgia’s version of the Whig Party, the States’ Rights Party. This change in Clayton’s national party affiliation led to his switching sides on major political issues. Clayton now supported the Second Bank of the United States against Jackson, and he held his tongue on the issue of the tariff, which was favored by the Whig Party nationally. On a private level, in 1834 Clayton and Cherokee chief John Ross met for the first time, at Clayton’s apartment in Washington, D.C., and Clayton apologized for his actions against the Cherokees. He was also rumored to have ghostwritten the anti-Jackson book Life of Martin Van Buren (1834) by Davy Crockett, who was serving with Clayton in Congress at that time as a representative from Tennessee.

In 1834 Clayton decided to make a run for the Georgia governor’s office, but his constituency had noted the change in his party affiliation. The Democratic press regularly lampooned Clayton, and the “profane” statement he had made as a nullifier in 1832 was brought to the public’s attention again and again. The party he had helped to found ultimately abandoned him, and he withdrew from the gubernatorial race in June 1835. Clayton continued to advocate states’ rights issues, albeit with a decidedly Whig approach.

In 1838 Clayton suffered a debilitating stroke and, having formerly expressed skepticism about organized religion, publicly converted to Methodism, his wife’s faith. In doing so, he apologized for his previous unbelief, hoping to make an example of his own conversion to evangelical Christianity. He died on June 21, 1839, at his home in Athens. Ministers of the city’s three main churches showed their respect by jointly officiating at his funeral and publishing the main funeral oration. The state named Clayton County in his honor in 1858.