Among the more consequential U.S. Supreme Court cases of the late twentieth century, Bowers v. Hardwick (1986) upheld the constitutionality of a Georgia sodomy law that criminalized consensual gay sex within one’s private residence. The Georgia Supreme Court invalidated the same law in 1998, and in 2003, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned its earlier ruling in Lawrence v. Texas.

Background

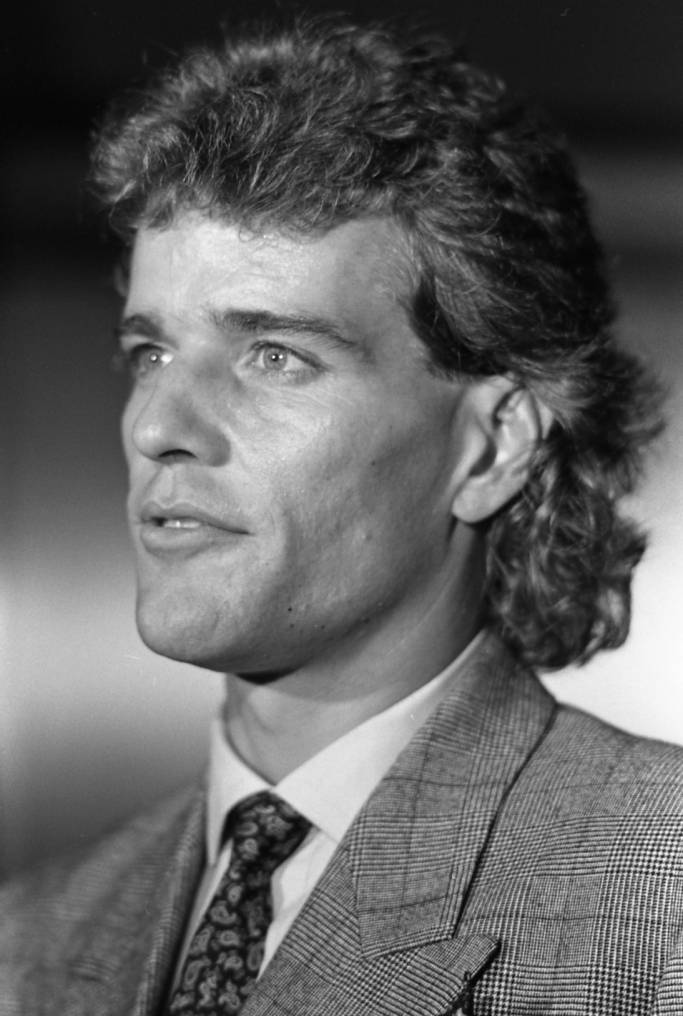

Michael Hardwick was born in Miami, Florida in 1954. Raised in a middle-class family, he graduated high school, studied botany at a local college, and found work in a nursery. While visiting Atlanta, he became romantically involved with another man. “I was totally straight up to that point,” he later recalled, “but there was an attraction.” After embracing his identity, Hardwick moved to Atlanta in 1979 and found work as a bartender in a gay bar.

In July 1982 Hardwick tossed a beer into the garbage outside the gay discotheque where he worked in Atlanta. A police officer, Keith Torick, witnessed the act and, after a brief verbal exchange, issued a ticket for public drinking. Hardwick then missed his court date, and the police issued a warrant for his arrest. Realizing his error, Hardwick later reported to the county clerk and was fined fifty dollars.

Officer Torick was unaware that Hardwick’s account was settled, however, and in the early morning hours of August 3, 1982, he entered Hardwick’s home to serve the warrant. He walked unannounced into the bedroom and discovered Hardwick engaging in consensual oral sex with a male schoolteacher. Torick then confiscated a small amount of marijuana and arrested Hardwick on sodomy charges.

At the time, Georgia was one of more than a dozen states that maintained anti-sodomy statues. Though most often applied to gay men, Georgia’s law was broadly written and could also pertain to straight couples or married partners who performed certain sexual acts. The law, which was punishable by as many as twenty years in prison, was applied infrequently by the 1980s, but effectively criminalized gay life.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) had been waiting for years to find an ideal case to challenge the law, and Hardwick’s arrest fit their criteria. Clint Sumrall of the Lesbian/Gay Rights ACLU chapter approached Hardwick three days after the incident, and he agreed to try the case. “I realized…that I would feel pretty bad about myself if I just walked away from it,” Hardwick later reflected. “I was fortunate enough to have a supportive family who knew I was gay. I’m a bartender, so I can always work in a gay bar. And I was arrested in my own house. So I was a perfect test case.”

Legal Case

Hardwick pled guilty for possession of marijuana, but district attorney Lewis Slaton dismissed the sodomy change, arguing that such laws should not be applied to consenting adults acting in private—regardless of their sexual orientation. Yet the very existence of such statutes posed a threat to the gay community, and the ACLU sought to challenge the constitutionality of sodomy laws in court.

On Valentine’s Day 1983, lawyers John Sweet and Kathy Wilde of the ACLU filed a complaint in the district court against Georgia attorney general Michael Bowers, district attorney Lewis Slaton, and Atlanta Public Safety Commissioner George Napper. Hardwick was one of the plaintiffs. A heterosexual married couple (John and Mary Doe) were also named as plaintiffs, but were later dropped from the case.

The United States District Court for the Northern District of Georgia dismissed the case and ruled in favor of Bowers. This decision was then overturned by the United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit, which found the statute unconstitutional. Bowers then appealed to the United States Supreme Court, which agreed to review the case.

Oral arguments were heard in Washington D.C. on March 31, 1986, with respected Harvard legal professor, Laurence Tribe, representing Hardwick. At the time, Hardwick and his supporters had reason to believe the court would rule in his favor. More than twenty years earlier, Griswold v. Connecticut (1965) had recognized the privacy of married couples to buy and use contraception and more recent cases had established “substantive due process” precedents that placed private matters beyond the reach of governmental regulation. Building upon these cases, Hardwick’s attorneys contended that a right to privacy was implicit in the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

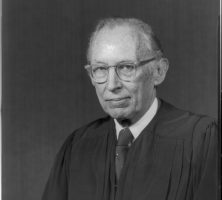

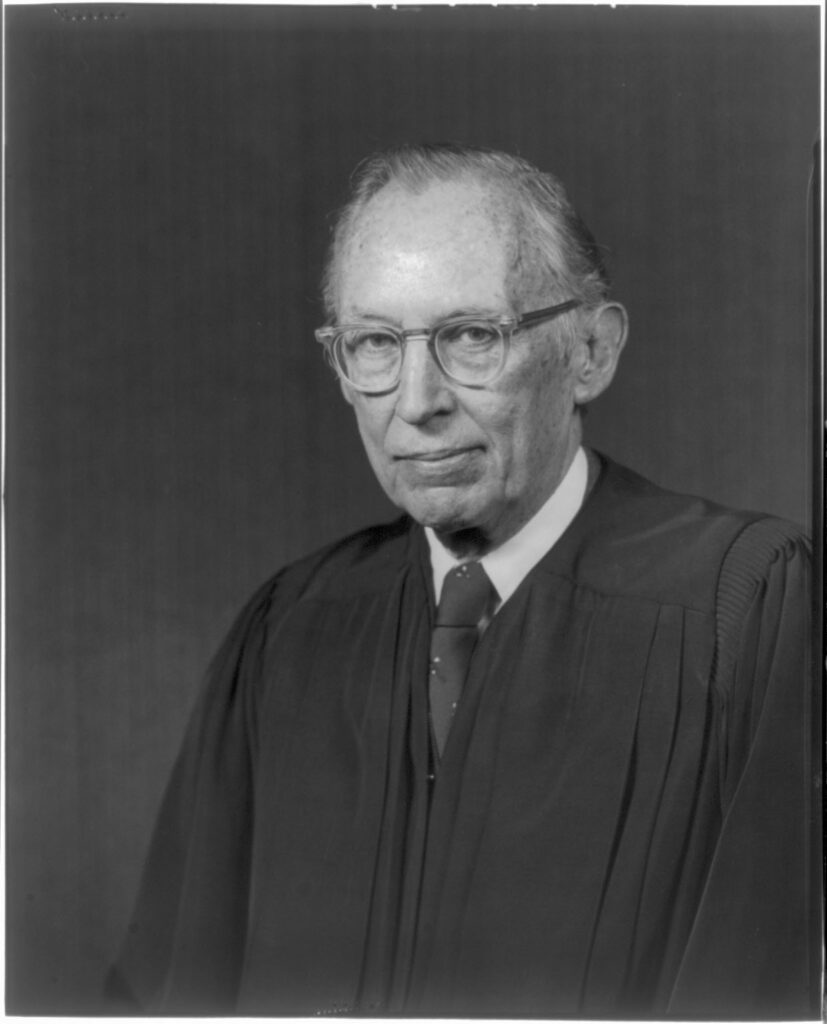

In a 5-4 ruling, the United States Supreme Court upheld the Georgia’s statute as constitutional. The majority opinion, written by supreme court justice Byron White, contended that “the Constitution does not confer a fundamental right upon homosexuals to engage in sodomy.” According to the court, the “right to privacy” protected some aspects of marriage, procreation, contraception, and family relationships, but it did not protect gay sodomy from interference from the state because “no connection between family, marriage, or procreation on the one hand and homosexual activity on the other has been demonstrated.”

After retiring from the bench, Justice Lewis Powell, who had provided the critical fifth vote, reflected on his decision, saying, “I think I probably made a mistake in that one.”

Outcome

Despite losing the case, Hardwick emerged as an icon in the gay community, becoming an effective spokesperson for LGBTQ+ rights. Allies of the movement were also undeterred by the decision, and many in the gay community believed the publicity surrounding Bowers v. Hardwick helped illumine their ongoing struggle for equal rights. Legal advocacy continued as well, and in 1998, the state supreme court declared Georgia’s sodomy law unconstitutional. Writing for the majority in Powell v. The State, Chief Justice Robert Benham concluded, “we cannot think of any other activity that reasonable persons would rank as more private and more deserving of protection from governmental interference than unforced, private, adult sexual activity.”

Though Powell may have settled matters in Georgia, Bowers remained a national precedent until 2003 when it was explicitly overturned in Lawrence v. Texas, which held that sodomy laws violated the Fourteenth Amendment’s due process clause. According to the 6-3 decision delivered by supreme court justice Anthony M. Kennedy, consenting adults had a right to privacy and “the liberty protected by the Constitution allows homosexual persons the right to choose to enter upon relationships in the confines of their homes and their own private lives and still retain their dignity as free persons.” In short, the court concluded, “Bowers was not correct when it was decided, is not correct today, and is hereby overruled.” This landmark case invalidated sodomy laws in thirteen states.

Hardwick never lived to see his case overturned. On June 13, 1991, he died near Gainesville, Florida from complications caused by AIDS. His obituary made no mention of his sexual orientation nor his role in the famous supreme court case.