Despite the rejection of broadside attacks on capital sentencing in cases like Gregg v. Georgia (1976) and McCleskey v. Kemp (1987), litigants have successfully challenged particular features of state death-penalty laws in a number of U.S. Supreme Court cases. An especially significant ruling came in Coker v. Georgia (1977), which invalidated Georgia’s effort to extend eligibility for the death penalty to persons convicted of the crime of rape.

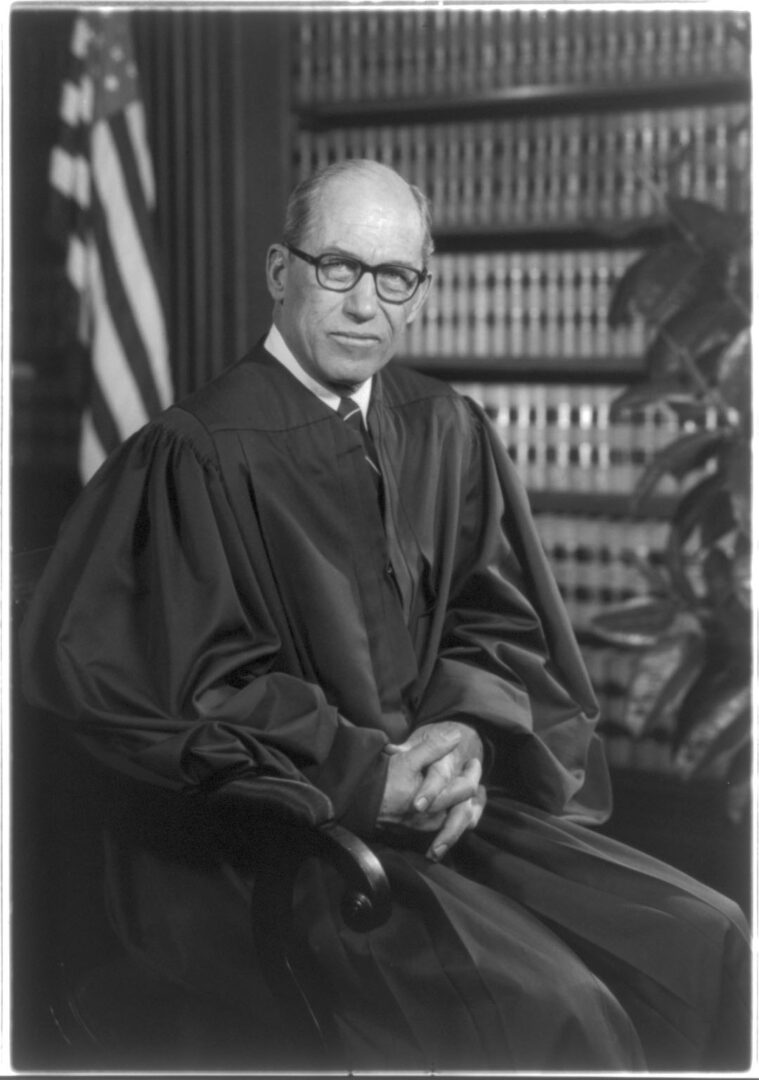

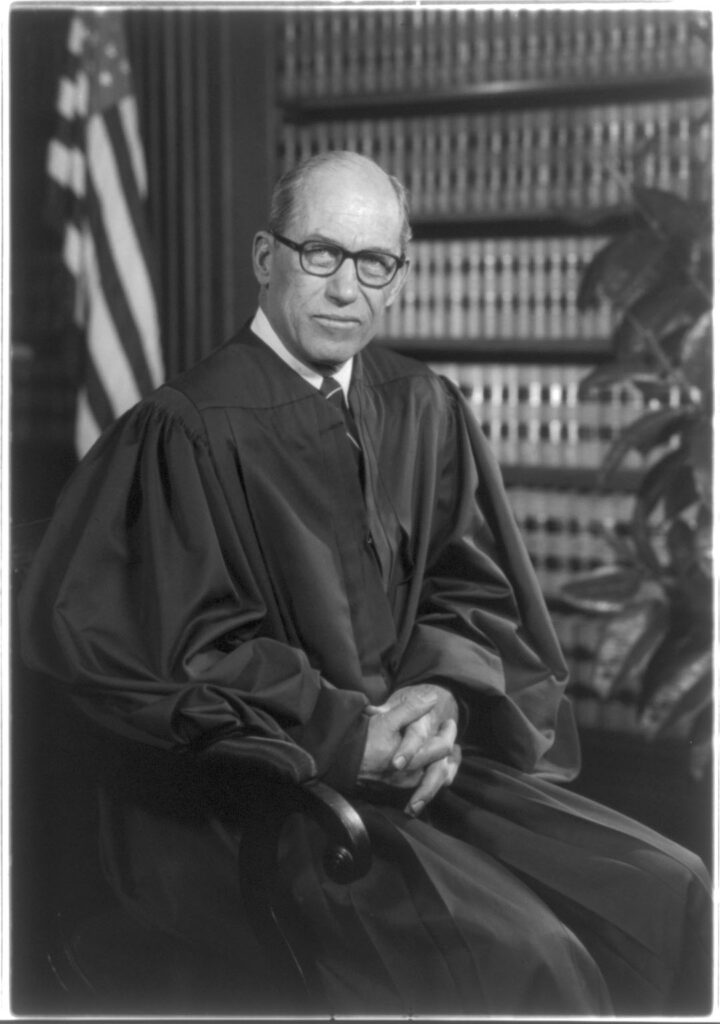

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

In 1974 Ehrlich Anthony Coker was serving multiple life sentences in a Georgia prison for rape, murder, assault, and kidnapping. But on September 2 of that year, Coker escaped from jail. Following his escape, he entered the home of Elnita and Allen Carver, a married couple who lived near Waycross, and raped Elnita. He then stole the couple’s car and forced Elnita to ride away with him, warning her that he would kill her if the police intervened. But shortly afterward, the police apprehended Coker, and a jury sentenced him to death for the rape of Elnita Carver. The Supreme Court of Georgia sustained Coker’s death sentence. On June 29, 1977, however, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the verdict and announced that the U.S. Constitution prohibited Georgia from executing a person as punishment for rape.

In finding this feature of the Georgia death-penalty law unconstitutional, the Supreme Court reasoned that punishments violate the Eighth Amendment if they are “excessive in relation to the crime committed,” that determinations about excessiveness are properly informed by the “country’s present judgment,” and that the Georgia law could not survive this type of inquiry because no other state subjected persons convicted of the rape of an adult woman to execution.

Coker has been read to establish that governments may not extend the death penalty to most, and perhaps to all, nonmurder offenses. In addition, the Court has drawn on the underlying excessiveness rationale of Coker in later cases to invalidate death sentences even in some categories of murder cases—such as cases involving murders committed by persons with intellectual disabilities or persons who are younger than sixteen years of age.

Justice Byron White wrote the majority opinion in Coker, and seven justices agreed that the death sentence imposed in the case should be overturned. Chief Justice Warren Burger, joined in dissent by Justice William Rehnquist, criticized this result, stating that “rape is not a minor crime” and “the Cruel and Unusual Punishments Clause does not give the Members of this Court license to engraft their conceptions of proper public policy onto the considered legislative judgments of the States.”