George Mathews, a veteran of the Continental army during the Revolutionary War (1775-83), migrated to Wilkes County from Virginia between 1783 and 1784. He quickly rose to service as a state legislator, governor, and member of the U.S. Congress.

Early Life and Career

Mathews was born in 1739 to Ann Archer and John Mathews, Ulster immigrants, and spent his formative years in Augusta County, Virginia. His family diligently sought recognition as members of the western Virginia gentry, and Mathews exerted his efforts in economic, civil, and military affairs. He joined his elder brother, Sampson, in a business partnership that included land speculation, property leasing, agricultural, and mercantile operations. The brothers’ enterprise extended from Staunton, Virginia, to the Greenbriar district of western Virginia and grew to include an extensive Atlantic trade network. Mathews used his circles of influence to obtain appointment to the Augusta Parish vestry, as a county magistrate, and as high sheriff.

As Virginia supported the growing rebellion against Great Britain, Mathews eagerly sought a military command. Revolutionary leaders of the colony applauded his persuasive and skillful leadership as a militia captain during the 1774 Battle of Point Pleasant, and by 1777 Mathews obtained appointment as colonel of the Ninth Virginia Regiment. His troops were assigned to Continental service under General George Washington, but during the Battle of Germantown in Pennsylvania, the entire regiment was either killed or captured. Mathews remained a prisoner of war until December 1781.

Settling in Georgia

Shortly after his release Mathews rejoined the Continental army in Georgia and South Carolina. His sojourn there provided an opportunity to view the rich lands of the Georgia upcountry. By January 1783 Mathews worked with several Virginians, including Colonel George Rootes, Francis Willis, and John Marks, to petition the state legislature for a block grant of 200,000 acres in the Georgia backcountry on which to settle 30 to 100 Virginia families. But assembly members rejected the creation of such an extensive tract. Mathews opted to purchase property in the Goose Pond region of Wilkes County, Georgia, near the Broad River, and obtained additional state lands for his revolutionary service. He returned to Virginia and encouraged family, friends, and former compatriots (including Benjamin Taliaferro) to settle in Wilkes County.

Mathews eliminated most of his mercantile connections upon his move to Georgia. He lived in a log cabin with his wife, Anne Polly Paul, and their eight children, John, Charles Lewis, George, William, Ann, Jane, Margaret, and Rebecca. As in Virginia, Mathews sought to create an image of a member of the enslaver, planter-elite . He sought entrance into the public and political life of the Georgia backcountry and employed a strong network of wartime associates, friends, family, and economic contacts to achieve his goals. Mathews quickly obtained appointment as a Wilkes County justice and as a commissioner for the new town of Washington, and he successfully stood as a candidate to the Georgia Assembly in 1787. Legislators took advantage of his reputation as an aggressive military leader and Continental officer and elected Mathews as governor for 1787-88.

The Georgia Governorship and the Yazoo Land Fraud

As the new chief executive Mathews chafed at the restrictions placed upon the independence of the governor by the Georgia Constitution of 1777, which prevented his quick response to border conflicts with the Spanish and Creek Indians. His term in office prompted an advocacy for stronger state and national government, and Mathews served as a member of the 1787 state convention to ratify the new federal constitution. The following year western residents elected Mathews as a member to the House of Representatives. In spite of a lackluster term, defeat in 1791 by a land speculation faction called the Combined Society, and failure to win a federal senatorial seat in 1792, Mathews rebuilt political support and maneuvered legislative election as governor in 1793.

During Mathews’s second administration Georgia faced renewed Creek raids along the frontier. A lack of assembly and federal military funding frustrated his defense plans for a chain of blockhouses along Georgia’s frontier, as did the actions of a fellow Wilkes County resident, Elijah Clarke, who posed as a French agent and established an illegal settlement in Creek lands called the Trans-Oconee Republic. Mathews, conscious of maintaining strong political support, may have turned to the use of land grants as a means of retaining popularity. He continued to practice a policy of his predecessors, known historically as the Pine Barren Speculation, and granted extensive tracts—some as large as 40,000 acres—in Effingham, Franklin, Glynn, Liberty, McIntosh, Montgomery, and Washington counties.

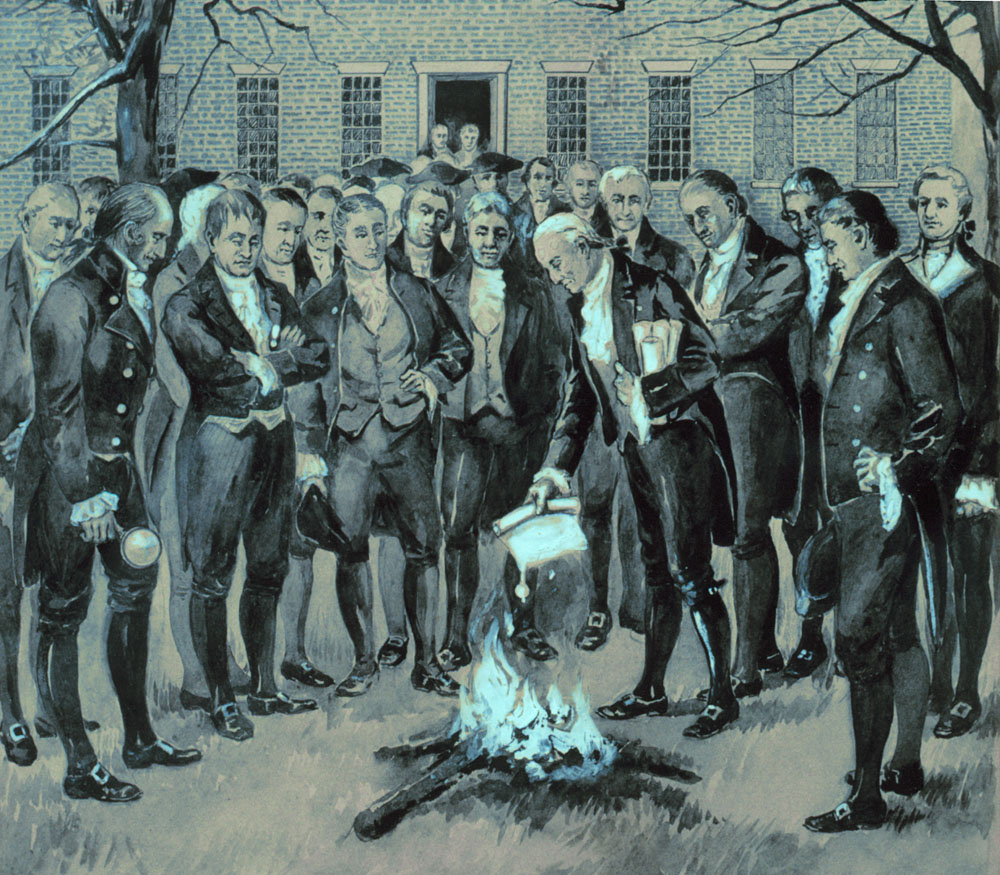

In 1795 private land companies revived a failed 1789 effort to purchase the state’s western land claims extending to the Mississippi River. At first Mathews stood firm against signing the Yazoo land bill, but earlier activities as a land speculator and his desire to maintain public approval may have prompted Mathews’s acceptance. His approval of the Yazoo sale catapulted him into political disgrace. Opponents, led by a former U.S. senator, James Jackson, accused Mathews of identification with the self-interest of speculation and of failing to exhibit Republican independence. Since most of the anti-Yazooists followed the principles of the rising Jeffersonian-Republican faction, Mathews’s identification with the Federalists intensified those accusations.

Later Life and Career

Mathews sought a new life in Mississippi Territory, where he married a propertied widow, Mary Carpenter. His efforts to revive his political career included an 1812 commission by U.S. President James Madison to encourage an East Florida rebellion against the Spanish government and annexation of that territory to the United States. The revolt took place, and Mathews began to organize an attack on St. Augustine, Florida. But he worked too successfully. Members of the federal government felt it politically inexpedient to acquire Florida at that time, and the president issued a recall to Mathews. Mathews took the rejection of his Florida efforts personally. He started to travel to Washington, D.C., to confront the president but fell ill while passing through Augusta. There he died and was buried in the cemetery of the St. Paul Episcopal Church.