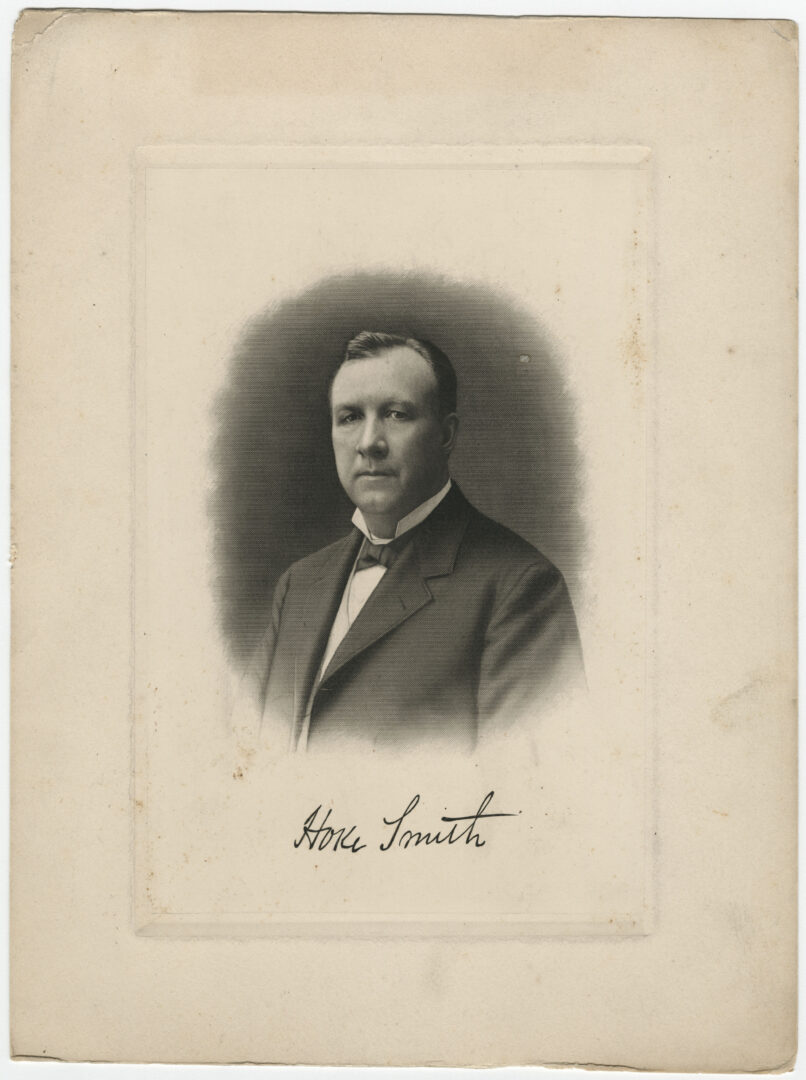

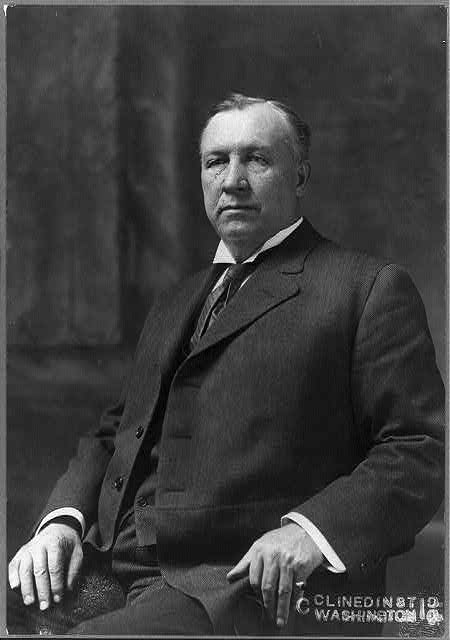

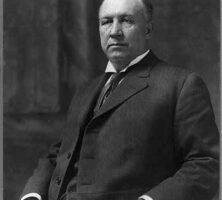

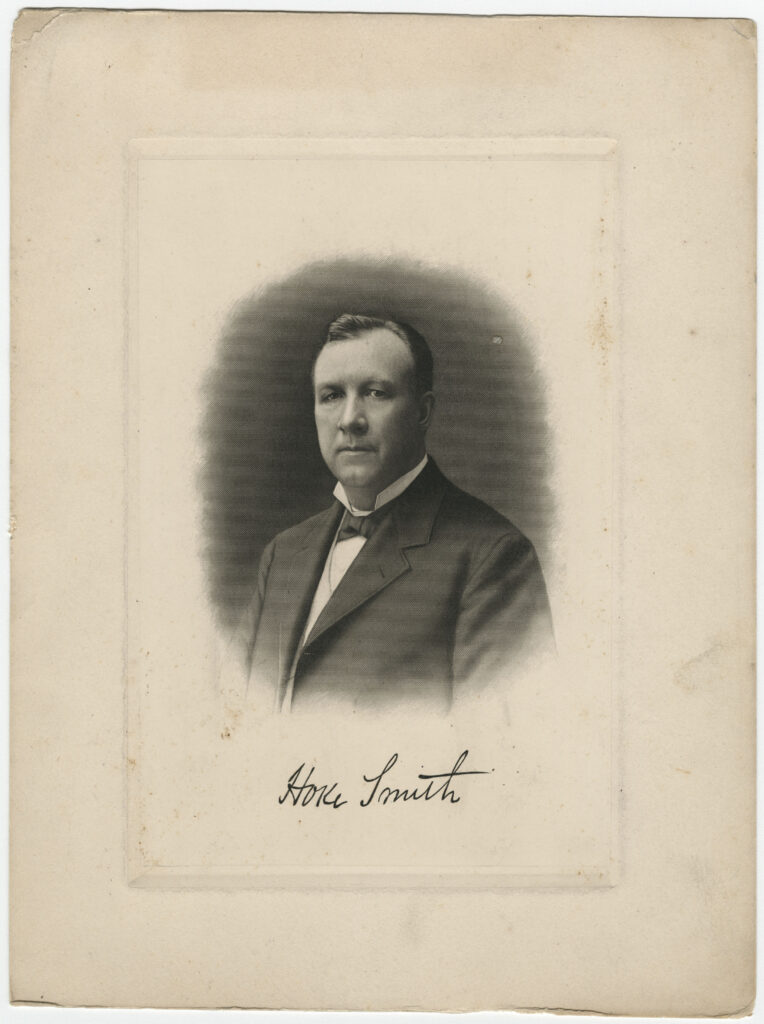

Hoke Smith, a trial attorney and publisher of the Atlanta Journal, was most influential as the leader of Georgia’s Progressive movement during his years as governor (1907-9, 1911) and as a U.S. senator (1911-21). His racial views, as expressed during the 1906 gubernatorial campaign, directly contributed to the Atlanta Race Massacre of 1906.

Early Life

Michael Hoke Smith was born on September 2, 1855, in Newton, North Carolina, to Hildreth H. Smith, a New England educator then serving as president of Catawba College, and Mary Brent Hoke, a member of a prominent North Carolina family. The Smiths moved to Chapel Hill in 1857, when Smith’s father joined the faculty at the University of North Carolina. Hoke was too young for military service during the Civil War (1861-65) and instead remained at home in the university community under the tutelage of his father, whose keen instruction enabled the boy to rise to legal and political heights without formal education.

In 1868 Smith’s father lost his position at the university and moved his family to Atlanta, after accepting a post in the city’s public school system. Smith immediately set out to establish his own place in the city. He read for the law at an Atlanta firm, proving the quality of his father’s instruction by passing the bar examination at the age of seventeen in 1873. Although he began his legal practice with few connections and fewer assets (he saved money by sleeping in his office), he rose to become one of the most prominent injury attorneys in the Southeast, representing workers and passengers against the railroads. As he became financially and professionally established, Smith mirrored his father’s devotion to education by serving on the Atlanta Board of Education, first as a member in the 1880s, then as its president (1896-1907). In 1883 he married Marion “Birdie” Cobb, daughter Thomas R. R. Cobb, one of the South’s foremost defenders of slavery; together they had five children.

Political Career

Smith used his growing wealth to purchase the Atlanta Journal in 1887, soon building it into the archrival of the Atlanta Constitution. The investment demonstrated his skills as a businessman and publisher; in only thirteen years the initial $10,000 investment had grown to $300,000. In addition to being profitable, the Journal gave Smith a public platform , which he used to enter Democratic politics and later promote his racist ideology. The paper’s promotion of Grover Cleveland’s successful 1892 presidential campaign led to Smith’s appointment as U.S. secretary of the interior (1893-96). Smith resigned when Cleveland lost the 1896 Democratic nomination to William Jennings Bryan, the noted orator and proponent of free-silver monetary policy.

Supporting Bryan effectively allied Smith with Thomas E. Watson’s Populist Party because the Populists had also nominated Bryan as their presidential candidate, with Watson as his vice-presidential running mate. The election resulted in a solid victory for the Republican candidate, William McKinley, and in a crushing defeat for the Populists both nationally and in Georgia. Smith’s association with them made him a political exile in Georgia for most of the next decade.

1906 Gubernatorial Race

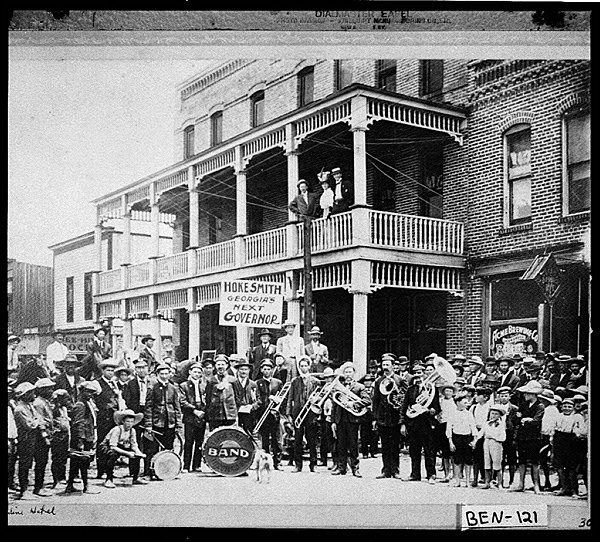

Smith resurfaced in Georgia Democratic politics when he entered the 1906 gubernatorial race against Clark Howell, publisher of the rival Atlanta Constitution. While Smith led by a slim margin, the race for the Democratic nomination was close and contentious. Both candidates, given their respective newspaper affiliations, used the power of the press to influence public opinion.

In order to gain public favor, Smith once again sought the support of populist Thomas E. Watson, an ardent segregationist and white supremacist. Indeed, Watson had not been a disinterested supporter in this election; he lent his political support on the condition that Smith would disenfranchise Black voters. In turn, the campaign advocated for the total disenfranchisement of Black voters and embraced race-baiting tactics that played upon white fears of Black manhood and miscegenation. Smith’s racist message was clear: allowing Black men access to the ballot box was akin to granting them sexual domination of white women.

Lurid and false accounts of the rape and assault of white women subsequently appeared in newspapers across the state, inflaming racial tensions and pandering to white fears of a Black upper class, particularly in Atlanta. This rhetoric directly contributed to the Atlanta Race Massacre of 1906, in which a white mob killed dozens of Black Georgians, wounded countless others, and destroyed Black-owned property.

Governorship

Smith was elected to the governorship, and devoted his first term (1907-9) to a flurry of Progressive legislation: he greatly strengthened the Railroad Commission’s power to regulate railroads, increased public school funding, established the juvenile court system, and abolished the notorious convict lease system. As was true throughout the South, Jim Crow racism was central to the Progressive movement in Georgia. Smith kept his promise to Watson by leading the adoption of a constitutional amendment to impose a grandfather clause that effectively disenfranchised Black Georgians.

The volatile Watson nonetheless transferred his support in the 1908 governor’s race from Smith to Joseph M. Brown in retaliation for Smith’s refusal to commute the death sentence of a Watson supporter. The race was a grudge match not only with Watson but also with Brown, who sought political revenge after Smith had fired him from the Railroad Commission for being too favorable to the railroads. Although Smith lost the 1908 election, he won a rematch against Brown in 1910.

Soon after Smith began his second term in 1911, the General Assembly elected him to fill Georgia’s U.S. Senate seat held by Joseph M. Terrell, who had suffered a major stroke. The legislature expected Smith to resign the governorship immediately for the new office, but he refused to comply. Instead, he frustrated his opponents by remaining as governor until the end of the 1911 legislative session in order to extend his Progressive agenda. He created the Department of Commerce and Labor, established the state Board of Education, reduced the maximum work week for textile workers to sixty hours, and passed an anti-lobbying bill.

Later Career

At the end of the session, Smith entered the U.S. Senate, where he led the passage of the Smith-Lever Act (1914) to create a national agricultural extension system and the Smith-Hughes Act (1917) for vocational education in secondary schools. Smith continued to face opposition from Joseph M. Brown and Tom Watson in his Senate reelection campaigns. He defeated Brown in 1914 but lost to Watson in 1920. The defeat marked the end of Smith’s political career.

He stayed in Washington, D.C., to practice federal claims law until 1924; that same year he married Mazie Crawford, his first wife having died in 1919. Smith returned to Atlanta in 1925 and remained active in legal and civic affairs there until his death in 1931. Given Smith’s legislative initiatives in business, government, and education, he is often considered one of Georgia’s leading Progressive reformers.