Few cities in America have a daily newspaper that has published continuously for more than 100 years. Until recently, Atlanta had two—the Atlanta Constitution, first published on June 16, 1868, and the Atlanta Journal, which debuted on February 24, 1883. The longtime rivals, which had been under common ownership since March 1950, merged on November 5, 2001, and are currently published daily under a joint masthead. The Journal-Constitution is the largest daily newspaper in the Southeast, with an average daily circulation of 640,000.

The Journal and Constitution have won numerous Pulitzer Prizes and have nurtured the careers of many famous journalists, including: Henry W. Grady, whose lobbying efforts set the stage for the South’s agricultural and industrial growth following a difficult Reconstruction period; Joel Chandler Harris, whose colorful Uncle Remus tales —African American folk tales written in dialect—first appeared in the Constitution; Margaret Mitchell, the author of the international best-seller Gone With the Wind; Ralph McGill, a passionate voice of reason in the early days of the civil rights movement, whose personal essays—a new journalistic form—ran on the front page of the Constitution.

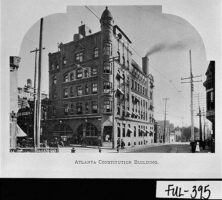

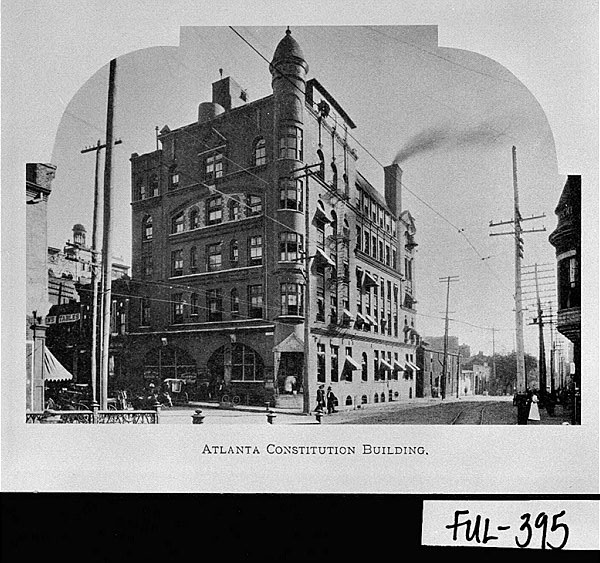

Early History of the Constitution

The Constitution was founded in 1868 by Carey Wentworth Styles, an Atlanta lawyer and entrepreneur. He bought the Atlanta Daily Opinion, one of several newspapers serving the city’s 20,288 residents, and renamed it the Atlanta Constitution. Legend says the new name was suggested by U.S. president Andrew Johnson, who thought it apt for a Democratic newspaper advocating the restoration of constitutional government (Georgia remained under federal military rule at the time).

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

Six months later Styles moved to Texas and sold his interest to his partner, James Anderson, who subsequently passed it to William Arnold Hemphill, his son-in-law and the paper’s business manager. Hemphill served as principal owner and publisher until 1901. In 1876 Evan P. Howell bought an interest in the Constitution and became its president and editor-in-chief, positions he held until 1897. Both Hemphill and Howell served as mayor of Atlanta, Hemphill during his years as a Constitution executive and Howell after he retired from the paper.

Immediately after joining the paper, Howell hired twenty-six-year-old Henry W. Grady from the Atlanta Daily Herald as a political writer and later managing editor. Grady, in turn, talked Howell into hiring another young newspaperman, Joel Chandler Harris, as an associate editor. Harris, who was extremely shy and often stammered, grew up in Eatonton, but had come to Atlanta from Savannah to escape a yellow fever epidemic. His first “Uncle Remus” column appeared in the newspaper in 1878. Later Grady and Harris were joined by another literary light of the period, Georgia poet laureate Frank L. Stanton, whose poem “Might Lak’ a Rose!” was recited by schoolchildren and set to music.

Courtesy of Special Collections & Archives, Georgia State University Library.

Grady traveled the country as a correspondent, writing impressions of the North and its leaders for his southern readers and sending reports of southern development to northern papers. In 1880, at age thirty, he bought a one-quarter interest in the Constitution with $20,000 borrowed from Cyrus W. Field, promoter of the transatlantic cable. Grady understood that economic development was crucial to rebuilding the South, and he used the Constitution to promote the region at every opportunity. He encouraged the 1881 International Cotton Exposition, helped to found the Georgia Institute of Technology, and organized Atlanta’s first minor league baseball team. In early December 1889, a weakened Grady discounted the advice of his physician and went to Boston to speak on race relations. He became gravely ill and died on December 23 in Atlanta, at age thirty-nine.

Young Clark Howell had come to work at his father’s newspaper in 1884 after apprenticeships at the New York Times and the Philadelphia Press. After Grady’s death he became managing editor, and in 1897 he succeeded his father as editor-in-chief. In the fall of 1901 Howell acquired the Constitution stock owned by Hemphill, becoming the paper’s new owner. Hemphill retired in January 1902, and Howell assumed the presidency of the company at that time. The paper remained in family hands until 1950. Clark Howell was a consummate newsman and public servant. He served as director of the Associated Press news-gathering operation at its inception in 1900, was a Democratic National Committee member from Georgia for thirty-two years, and served two terms in the state legislature. He ran for governor in 1906 but was defeated by the powerful Hoke Smith, a former owner of the rival Atlanta Journal.

Early History of the Journal

The Atlanta Journal, an afternoon paper under the banner of founder E. F. Hoge, entered the city’s newspaper war early in 1883. Hoge had invested in the latest printing presses, which turned out a sparkling product, but it was old-fashioned reporting that propelled his newspaper in its first year. At about 4:30 a.m. on August 12, 1883, Atlanta’s nationally known hotel, the Kimball House, was destroyed by fire. The Constitution had already printed its Sunday edition, but the upstart Journal quickly produced an extra edition that was distributed statewide with the news. Compliments and credibility followed.

In June 1887 Hoke Smith, a successful young lawyer, bought the Journal from the ailing Hoge for $10,000. Smith initiated several innovations that promoted the Journal’s reputation and circulation, including the South’s first daily women’s page. Smith and the Journal were strong supporters of Democrat Grover Cleveland in the 1892 presidential election. When Cleveland was elected, he repaid Smith by appointing him to the cabinet as secretary of the interior, thus bringing national attention to Smith and to the Journal.

By 1900 the Journal employed 200 people and had a daily circulation of 30,000. Smith and several minority stockholders decided to sell the paper to James Gray, Morris Brandon, and H. M. Atkinson for $300,000—a handsome profit from a $10,000 investment only thirteen years earlier.

Innovation continued under the new management, most particularly under Gray, who served as editor and publisher. Specialized sports reporting was added in 1901, a Sunday edition in 1902, and one of the country’s first Sunday magazines in 1912. The Sunday magazine published original syndicated work by many of the leading writers of the time, such as Harold Ross, founder of the New Yorker magazine; novelist Erskine Caldwell; and humorist Will Rogers. The novelist Margaret Mitchell was a young staff writer for the Sunday magazine. Other noteworthy journalists employed by the Journal in the opening decades of the new century included two legendary sportswriters—Grantland Rice, called “the dean of American sportswriters,” and O. B. “Pop” Keeler, mentor and friend to golfer Bobby Jones. Mrs. S. R. Dull, whose Southern Cooking was published in 1928 and remains in print today, edited the Journal’s weekly food page for more than twenty years. Under Gray the Journal also took progressive editorial positions—becoming an early proponent of better roads to accommodate the infant automobile industry.

Courtesy of Atlanta History Center.

Gray died unexpectedly in 1917, at the pinnacle of his career. His daughter, Cordelia Inman Gray, married the brother of Otis Arnoldus Brumby, founder of the Cobb County Times (later the Marietta Daily Journal), and thus continued her family’s involvement in Atlanta-area newspapers. After Gray’s death Major John S. Cohen took over leadership of the Journal, serving as president and editor until his death in 1935.

Twentieth-Century Expansion

In March 1922 (a mere two years after KDKA-Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania had signed on as the nation’s first commercial radio station), the Journal was awarded the broadcasting license for WSB Radio. The call letters were drawn from the familiar greeting “Welcome South, Brother.” WSB began broadcasting with 100 watts of power, equivalent to the wattage of an ordinary light bulb today. In 1926 WSB joined the fledgling NBC network, and within a decade it had become a 50,000-watt powerhouse that could be heard at points throughout the country.

To keep up with the rival Journal, the Constitution entered the radio business on March 16, a day after WSB went on the air. The station’s call letters were WGM. A year later Constitution owner Clark Howell Sr. offered the station to Georgia Tech as a gift, which accepted it on behalf of the state. The license was allowed to expire in 1924, but the following year a new license was granted with the call letters WGST, standing for Georgia School of Technology. Operating as a commercial station with educational opportunities for students, the radio station was officially owned by the Board of Regents of the University System of Georgia. In 1974 the station was sold to a private corporation and remains on the air today.

Before and after World War I (1917-18), the Constitution editorialized for peace; the paper also supported U.S. president Woodrow Wilson’s proposal for a League of Nations. But that stance didn’t prevent Clark Howell Jr., the son of the Constitution’s publisher, from serving in the army in France. When he returned in 1920, Howell Jr. became the business manager of the Constitution, and in 1930 he was promoted to general manager. After his father died in 1936, he became publisher, and finally in 1938 he added the title of editor.

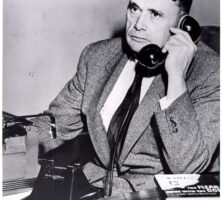

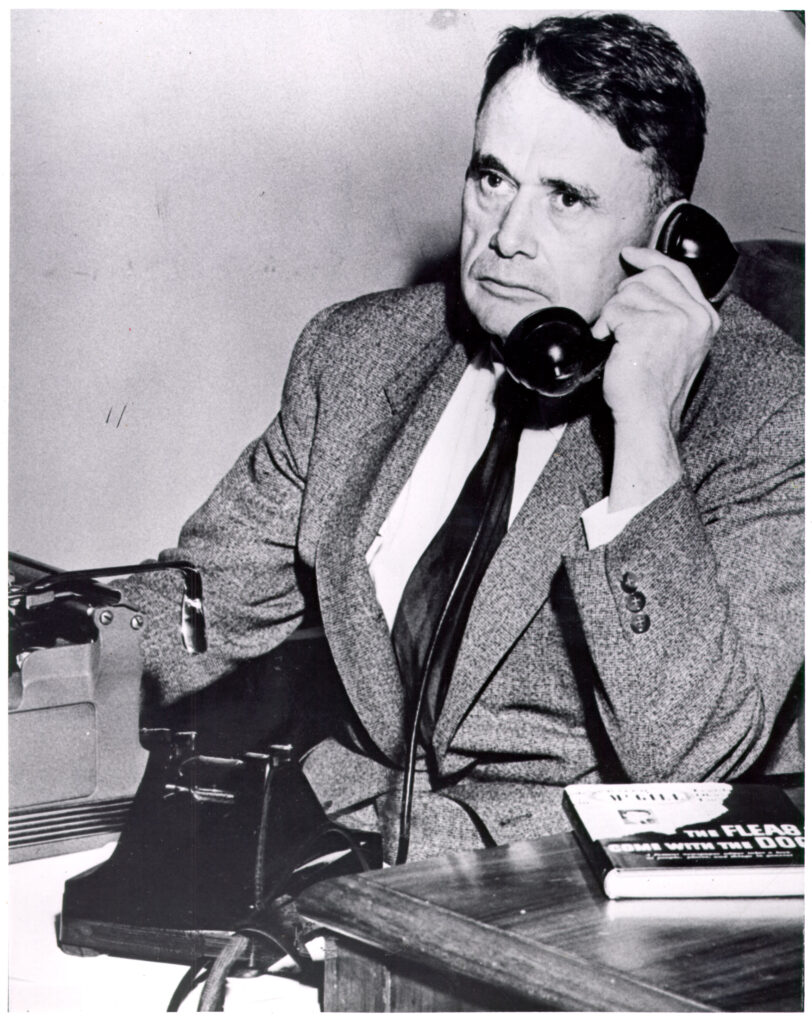

On April 2, 1929, the Constitution hired a young Tennessean named Ralph McGill as an assistant sports editor, thus launching the career of the most famous Atlanta journalist since Henry Grady. Two years later McGill became sports editor; he soon switched to general news reporting and in 1938 became executive editor. When McGill became the eighth editor of the Constitution in 1942, he began writing personal essay columns, which allowed him the latitude to address injustices and inequities wherever he found them. He urged the reform of farming practices, the elimination of the county unit system, and an end to prejudices that sullied the reputation of Georgia and the region. His powerful column about the bombing of Atlanta’s Jewish temple in 1959 won him the Pulitzer Prize for editorial writing. McGill’s moderate voice throughout the early years of the civil rights movement, which made him unpopular with many conservatives, is generally credited with helping Atlanta avoid the violence that attended the movement in many southern cities.

Courtesy of Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

McGill was named publisher of the Constitution in 1960 and served in that role until his death in 1969. The Constitution won two more Pulitzer Prizes under his watch: in 1960 for Jack Nelson’s exposé of deplorable conditions at the state mental hospital (later Central State Hospital) in Milledgeville, and in 1967 for Gene Patterson’s editorials.

After John Cohen’s death in 1935, the Journal was led by Inman Gray, the oldest son of former Journal president James Gray. But in December 1939 the Journal and radio station WSB were sold to James Middleton Cox, a nationally known statesman and journalist. With the purchase of the Dayton (Ohio) Daily News in 1898, Cox started what would grow to become a media empire. He soon went into politics, ultimately serving three terms as governor of Ohio. As the Democratic nominee for president in 1920, with Franklin D. Roosevelt as his running mate, he lost to Republican Warren G. Harding.

“I wouldn’t know of another property in America I would want outside of this one,” Cox wrote to a friend about his acquisition of the Journal. “Georgia is a great empire with an inescapable progress of agricultural development. That appeals strongly to me. The town is progressing more than any city in the South.” Cox was correct about Atlanta’s future, and the Journal flourished before and after his death in July 1957.

Merger

In June 1950, with the Journal pulling away from the rival Constitution in circulation (more than 300,000 copies on Sundays) and, more important, in advertising revenue, Cox acquired the Constitution and formed Atlanta Newspapers, Incorporated. Sales, administrative, and production operations were combined, but the newsrooms remained separate and competed fiercely for stories. The Constitution continued as a morning paper with a liberal editorial bent, while the afternoon Journal had a more conservative leaning. On Sundays the papers combined efforts to produce the Sunday Journal-Constitution.

George C. Biggers served as president of the combined newspapers until 1957, at which time Jack Tarver was named his successor. As an editorial columnist for the Constitution, Tarver was known for his satiric wit, but as publisher he also built a reputation as a no-nonsense businessman. He is often credited with “steadying Ralph McGill’s soap box” as McGill campaigned against social injustice during the civil rights movement; the coverage of sit-ins and demonstrations was very unpopular with some advertisers, who threatened to pull their ads, but Tarver kept their influence from reaching the newsrooms.

With a reputation for good writing and particularly strong sports coverage, the Journal led the rival Constitution in circulation until the late 1970s, when afternoon newspapers nationwide began losing circulation to morning editions. The combination of expanded evening television newscasts and traffic-related delivery problems in urban areas worked against afternoon newspapers.

In 1982 the Journal and Constitution finally combined their newsroom staffs into a twenty-four-hour operation, although they continued to produce two newspapers under distinct mastheads. As the Journal’s circulation continued to erode, especially in rural areas, the newspaper dropped its long-time slogan “Covers Dixie like the Dew.” In November 2001, with the Journal’s circulation under 100,000 copies (a level not seen since the early 1900s), the Journal and Constitution were merged into a single newspaper published daily under a joint masthead. The century-old battle between the two newspapers was over.

The Journal and Constitution fought off two serious challenges to their dominance in the last half of the twentieth century—from the Atlanta Times during the 1960s and from the Gwinnett Daily News (owned by the New York Times) in the 1990s. Today the Journal-Constitution is among the top twenty newspapers in circulation nationwide and is the most influential newspaper voice in Georgia.