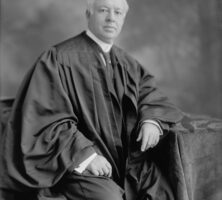

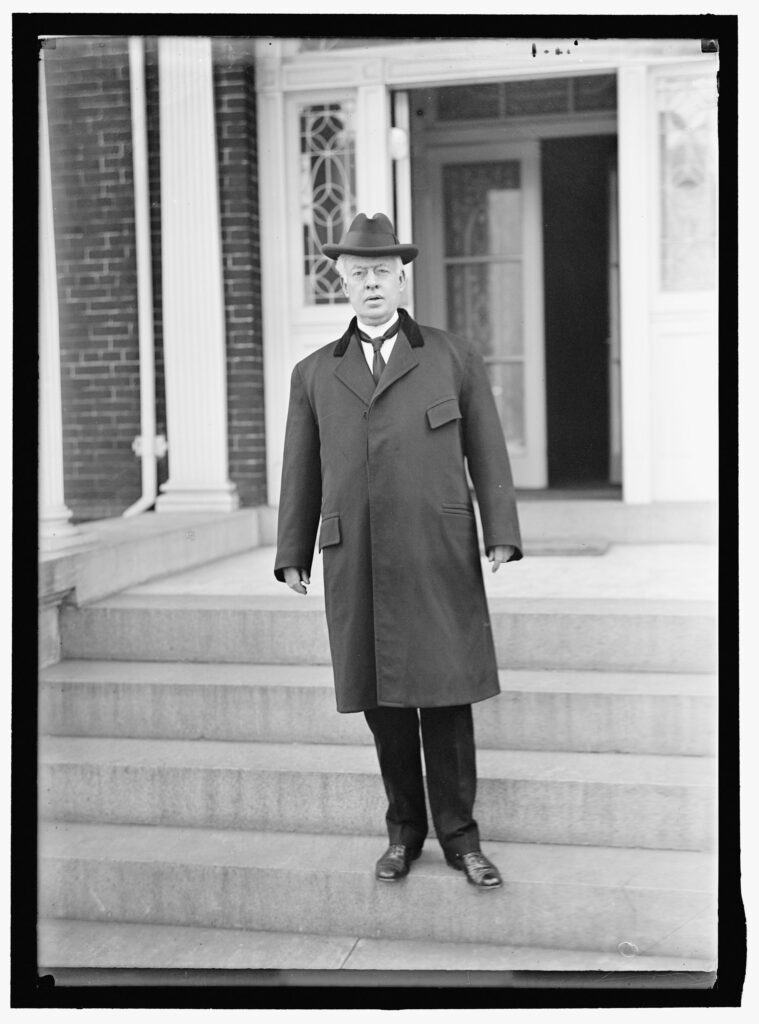

Joseph Rucker Lamar, an influential member of the Georgia legal community at the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth centuries, was the fourth native Georgian appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court. (His predecessors were James Moore Wayne, John Archibald Campbell, and Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar.) His appointment to the Court in 1910 by U.S. president William Howard Taft offered Lamar a chance to distinguish himself on the national stage. Unhappily, a limited docket and an untimely death gave Lamar little opportunity to make a national mark.

Early Life and Education

Lamar, born on the family plantation in Elbert County on October 14, 1857, to Mary Rucker and James Sanford Lamar, was a member of a prominent southern family. His father originally intended to pursue a legal career and was admitted to the Georgia bar in 1850. However, deeply influenced by Alexander Campbell, the president of his alma mater, Bethany College in West Virginia, James Lamar converted to a new Protestant sect, the Disciples of Christ, and became a pastor in Augusta.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Joseph and his brother and sister suffered a devastating blow when their mother died in January 1864. This traumatic event was compounded later that year when Union general William T. Sherman’s march to the sea forced the family to flee the area. In late 1865 his father remarried and returned to Augusta, and the family found itself living next door to the Presbyterian pastor Joseph Wilson, whose son, Woodrow, became Lamar’s close friend and classmate at Richmond Academy, a local private school. Woodrow Wilson would go on to become the country’s twenty-eighth president.

In 1870 Lamar and his brother were sent to Jefferson, in Jackson County, to attend the Martin Institute. In 1874 he began college at the University of Georgia in Athens, but illness forced him to withdraw before completing his second year. In the meantime, the family had moved to Louisville, Kentucky, and after spending some time at home recuperating, Lamar headed off to West Virginia with his brother to complete his undergraduate studies at Bethany College. After graduating in 1877, he began his legal education at Washington and Lee University, in Lexington, Virginia, but soon abandoned that formal route and returned to Georgia, where he read law with Henry Clay Foster, a prominent Augusta attorney. In April 1878, at age twenty, Lamar was admitted to the state bar.

Despite his newly achieved professional status, Lamar returned to Bethany College, where he taught Latin for a year. While there, he married Clarinda Huntington Pendleton, the daughter of Bethany president William K. Pendleton, on January 30, 1879. The couple had three children, two sons and a daughter; their daughter died in infancy.

Political Career

Now supporting a family, Lamar returned to the law in 1880, accepting an offer to join Foster, his former mentor, in Augusta. Lamar quickly established himself professionally, and the partnership, which continued until Foster’s death a decade later, thrived. Lamar made his first foray into politics in 1886, winning election to the Georgia state legislature at the age of twenty-eight. He focused his legislative efforts on legal reform, working to pass legislation that improved the efficiency of the state’s judicial system. Although he had promised not to seek reelection, friends and colleagues convinced him to run again.

In 1893 a board that included William J. Northen, the governor of Georgia, and Logan Bleckley, chief justice of the Supreme Court of Georgia, appointed Lamar to a commission charged with reviewing the state’s legal codes. In 1898 the state supreme court appointed him to the board that reviewed applicants for admission to the state bar. He served on that body for more than a decade, the last five years as chair. In addition, Lamar earned praise for a series of scholarly articles that he wrote on Georgia’s legal history.

By the start of the twentieth century, Lamar was recognized as one of Georgia’s leading attorneys, and when a vacancy occurred on the state supreme court in 1902, he was an obvious choice to fill it. While he served on the court for only two years, his work there further burnished his reputation, and his services were much sought after when he resumed private practice in a partnership with former judge E. H. Callaway.

U.S. Supreme Court Justice

For all his legal accomplishments, a vacation encounter was central to Lamar’s eventual appointment to the U.S. Supreme Court. An avid golfer, Lamar first made President Taft’s acquaintance in 1908, when they played golf together in Augusta shortly after Taft’s election. Lamar made a positive impression on Taft, who considered appointing him to the Commerce Court, but U.S. senator Augustus Bacon suggested the Supreme Court as a more fitting post. In December 1910 Lamar was nominated and easily confirmed for the seat vacated by William Henry Moody. He assumed his seat on January 3, 1911.

During Lamar’s five years on the bench, the Supreme Court was presented with few cases of real note, and he offered written dissents on only eight occasions. His opinion on Gompers v. Bucks Stove and Range Company (1911) is probably his best known. While based on a technicality, the Gompers decision affirmed, in a unanimous ruling, the general use of injunctions against labor boycotts. The ruling reveals the shared mind-set of the Court during Lamar’s tenure, which generally reflected the progressive spirit of the time by supporting increased governmental involvement in business and economic activities.

Although a Taft appointee, Lamar reconnected with his childhood friend, Woodrow Wilson, who was elected president in 1912. In 1914 Lamar accepted an appointment by Wilson to serve on a commission that negotiated the settlement of a dispute with Mexico, where military forces were clashing with civilian officials. U.S. intervention efforts, aimed at supporting Mexico’s democratically elected government, were resisted by the Mexican military and left the two nations on the brink of war. Lamar and his fellow commissioner, Frederick W. Lehmann, were able to resolve the situation and ease tensions between the continental neighbors.

While his efforts with Mexico were successful, they left the justice stressed and overworked, a condition that likely contributed to the paralytic stroke he suffered in September 1915. Lamar was unable to assume his seat on the Court at the start of the 1915 term, and his health declined rapidly. On January 2, 1916, he died at the age of fifty-eight, ending a career of unfulfilled promise.

The papers of Lamar and his wife are housed at the Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library at the University of Georgia.