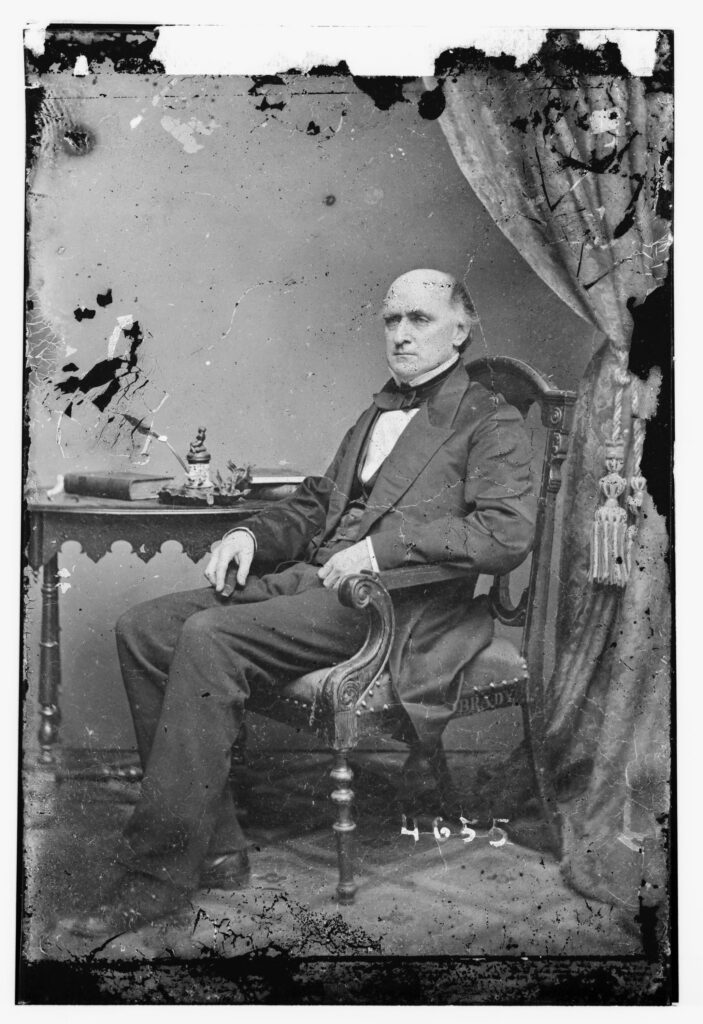

John Archibald Campbell, one of the most respected attorneys in the United States during the mid-nineteenth century, was appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1853. Caught up in the regional divisions that led to the Civil War (1861-65), however, Campbell never achieved the influence on the Court that his admirers and supporters expected.

Early Life and Education

Campbell was born on June 24, 1811, in Washington, the seat of Wilkes County, to Mary Williamson and Duncan Green Campbell. He was named for a Scots-Irish paternal grandfather who served on the personal staff of Nathanael Greene, a general during the Revolutionary War (1775-83).

The future justice grew up in high-powered academic circles and proved to be intellectually gifted. He graduated in 1825 with honors from Franklin College (later the University of Georgia) in Athens and then received an appointment to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York, from his father’s friend John C. Calhoun, a prominent South Carolina politician. Only fourteen when he enrolled, Campbell found West Point to be challenging. Languishing in the bottom third of his class, he resigned and returned home upon the sudden death of his father in 1828. Financial problems stemming from the senior Campbell’s political activities left the family in deep debt and forced the sale of the family homestead.

Legal Career

Recognizing that he could not return to West Point, Campbell decided instead to pursue a legal career. Accepting an offer to study with his uncle John Clark, Campbell moved to Florida in 1829 to read law, while also tutoring his cousin in order to earn additional income. He completed his studies in one year and was admitted to the Florida bar. Offered a clerkship in the U.S. District Court in Key West, Campbell considered practicing there but instead returned to Georgia, where he was admitted to the bar as well. Because he was only eighteen, his admission required a special act of the state legislature.

With the family finances still in disarray, Campbell decided to strike out in a new direction. He moved to Montgomery, Alabama, a city that offered much potential for growth, and established a successful law practice there. In 1830 he married Anna Esther Goldthwaite, a New Hampshire native who had settled in Alabama with her two brothers. Their marriage lasted fifty-three years, and the couple had five children—a son and four daughters.

As Campbell’s professional reputation grew, he made a foray into public life, winning election to the Alabama legislature in 1836. Despite long-held political aspirations, exposure to the gritty realities of politics left him disillusioned, and Campbell rededicated himself to his legal career. After moving to Mobile in 1837, his stature as one of the state’s leading attorneys continued to grow, and he had multiple offers to serve on the state supreme court—all of which he turned down. True to his scholarly roots, he assembled one of the finest law libraries in the country while becoming a recognized authority in both civil and common law. In addition, he gained a far-reaching reputation as a skilled courtroom advocate.

In 1851 Campbell made six impressive appearances before the U.S. Supreme Court, and two years later several of its members encouraged U.S. president Franklin Pierce to appoint him to the bench. Campbell was a states’ rights advocate who opposed secession, and his nomination to the Court enjoyed broad support but also reflected the geographic considerations central to the Court appointments of that era.

Supreme Court Justice

During his eight years on the bench, Campbell established a record that placed him in the mainstream of the generally homogeneous Taney Court. He wrote 116 total opinions, including 92 majority decisions, 5 concurrences, 1 statement, and 18 dissents. He also dissented 11 times without opinions. Campbell concurred with the decision in the controversial Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857) case, in which the Court ruled that enslaved people were not U.S. citizens and therefore did not enjoy the rights and protections guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution. He would have preferred, however, to decide the case on a more limited basis without addressing the question of Congress’s power to restrict slavery in the territories.

During the sectional crisis leading to the Civil War, Campbell was torn. Never a large slaveholder himself, he believed that the practice would eventually die out. He also insisted that enslaved people needed formal education and training before emancipation. Consequently, while he defended slavery, he also urged the South to refrain from seceding. Involvement in unsuccessful negotiations to prevent the war frustrated Campbell, and he resigned his position on the Court soon after hostilities began. Northerners criticized him for returning to Alabama, while Southerners, based on reports that mischaracterized his role in the prewar negotiations, were no more supportive. Returning to Mobile amid threats of violence, Campbell decided to move his law practice to New Orleans, Louisiana.

Confederate Service

In October 1862, with the Confederacy struggling to survive, he accepted an appointment as assistant secretary of war, overseeing the Confederacy’s draft laws. In January 1865 Confederate president Jefferson Davis appointed Campbell to a three-member peace commission that met with U.S. president Abraham Lincoln and U.S. secretary of state William H. Seward, but to no avail. When Lincoln visited a fallen Richmond, Virginia, on April 5, Campbell, the highest-ranking official remaining in the capital, met with him, but the discussion accomplished nothing. Confederate general Robert E. Lee surrendered a few days later.

Postwar Career

Although briefly jailed during the war’s aftermath, Campbell was among the first to petition U.S. president Andrew Johnson for amnesty. His home and property destroyed in the war, a bankrupt Campbell sought a quick return to civilian life and a restoration of his legal practice. Returning to New Orleans, he set up a partnership with his son, Duncan, and former Louisiana state supreme court justice Henry Spofford, but their efforts were hampered by numerous Reconstruction-era laws that restricted the practice in federal court of lawyers who had professed loyalty to the Confederacy.

In 1867 the Supreme Court ruled in Ex parte Garland that the law barring ex-Confederates from government service was unconstitutional, and Campbell once again became a frequent advocate before the Court. His most famous effort was undoubtedly the Slaughter-House cases (1873), and while the Court ruled against him, his interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment formed a central tenet of later civil rights cases.

Campbell’s legal practice thrived in the postwar period, but the sudden death in 1882 of his son and law partner, Duncan, followed in 1884 by the death of his wife, took an emotional toll. At seventy-three he moved to Baltimore, Maryland, where two of his daughters lived. He abandoned his general practice but accepted offers to argue before his former brethren, thereby reinforcing his stature within the legal community.

Campbell died in Baltimore on March 12, 1889, after a long illness.