Like other Southern states not readmitted to the Union prior to the end of the Civil War (1861-65), Georgia had to adopt a new constitution under the rules of Reconstruction. In fact, the state went through this process twice, as attempts to reunite the Union during and after the Civil War became a prolonged two-part process that divided the executive and legislative branches of the federal government. U.S. president Andrew Johnson’s policies, known as Presidential Reconstruction, prevailed until the beginning of Congressional Reconstruction in 1867. During Congressional Reconstruction, Radical Republicans in both the House and Senate seized control of the program from the executive branch and implemented much more rigid terms for bringing the former Confederate states back into the Union, as well as for the military occupation of the South.

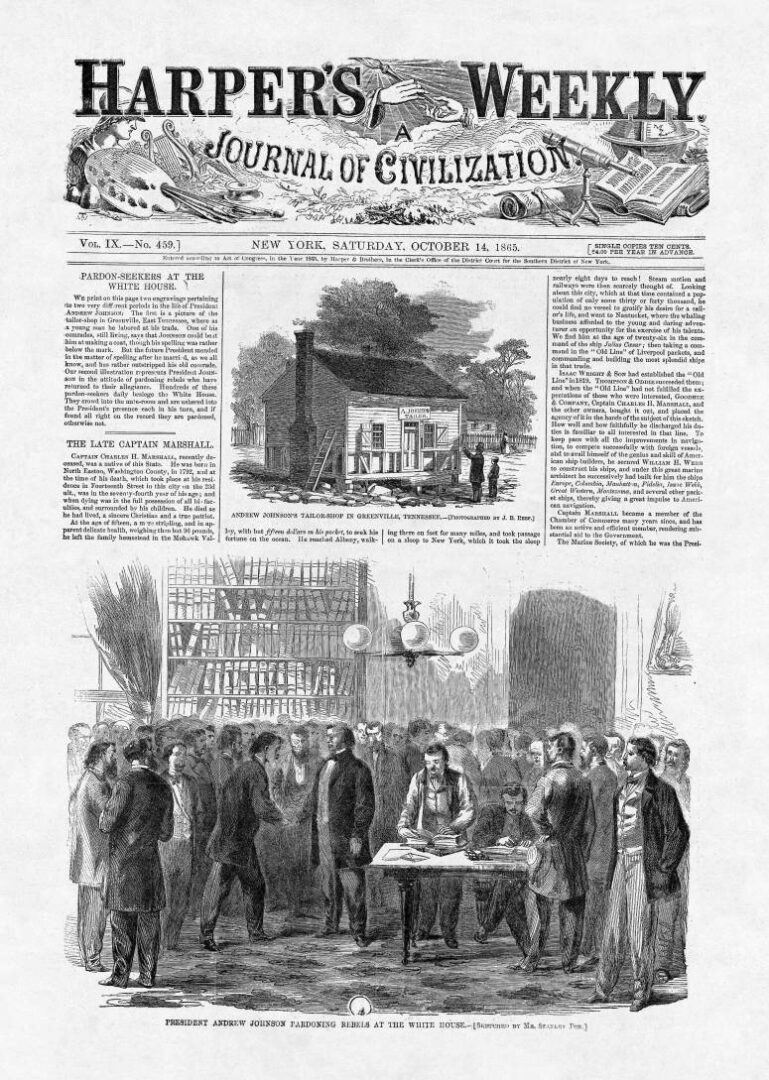

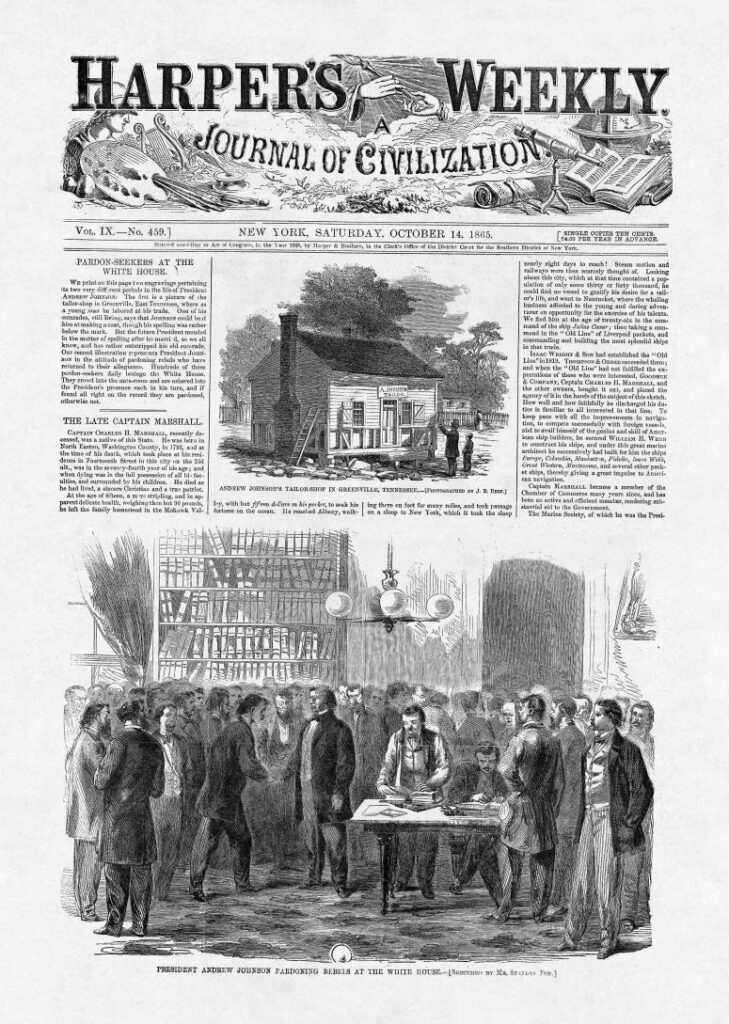

From Harper's Weekly

A constitutional convention in Georgia was held during both phases of the Reconstruction process as state leaders attempted to satisfy differing requirements by the federal government for returning to the Union. Both conventions assembled only under the guise of local authority since the Union government compelled their actions. Nevertheless, these meetings followed the protocols established by Georgians in previous years and allowed a degree of popular participation, though somewhat restricted by federal guidelines.

U.S. president Abraham Lincoln had proposed a plan of reconstruction as early as December 1863. Despite being objectionable to many Radical Republicans in Congress, his plan was relatively lenient on the seceded states that surrendered during his term. Lincoln’s untimely death made restoration to the Union more difficult for those states determined to fight to the end. Georgia surrendered too late to qualify for Lincoln’s terms for reunion and so was subject to Johnson’s policies.

One of the distinctions between the Lincoln and Johnson plans was the requirement for a state convention. In October 1865, 294 delegates met in Milledgeville in pursuance of the Johnson plan. Qualifications for delegates were more restrictive than they had been in previous conventions due to federal requirements. Although all delegates had to meet the same criteria required for the Georgia Secession Convention of 1861, they were additionally required to take an oath of loyalty accepting the U.S. Constitution, all federal laws, and the Emancipation Proclamation. Excluded from the outset were any citizens who had held high office or position within the Confederacy. Thus most of Georgia’s prominent political leaders at the time could not participate. A major exception was Herschel Johnson, who initially opposed secession in 1861 but succumbed to majority pressure. Johnson, in fact, became the president of the 1865 convention.

The delegates assembled and, as charged by Johnson’s plan, took up the business of rejoining the Union. They abolished slavery by ratifying the Thirteenth Amendment, repealed (rather than nullified, as technically required under Johnson’s plan) the state’s Ordinance of Secession, repudiated Georgia’s war debt, and wrote a new constitution. (The choice to “repeal” rather than “nullify” indicates a defiant statement of the state’s right to secede, even though many participating in the 1865 convention opposed secession in 1861.) After the convention, Johnson considered Georgia to be reconstructed. By engaging in all of the required activities beyond constitution making, the convention did not conform to the strict definition of a constitutional convention. In this way it was not unlike previous Georgia conventions, such as the convention of 1850 and the Secession Convention, in which other measures were discussed or adopted.

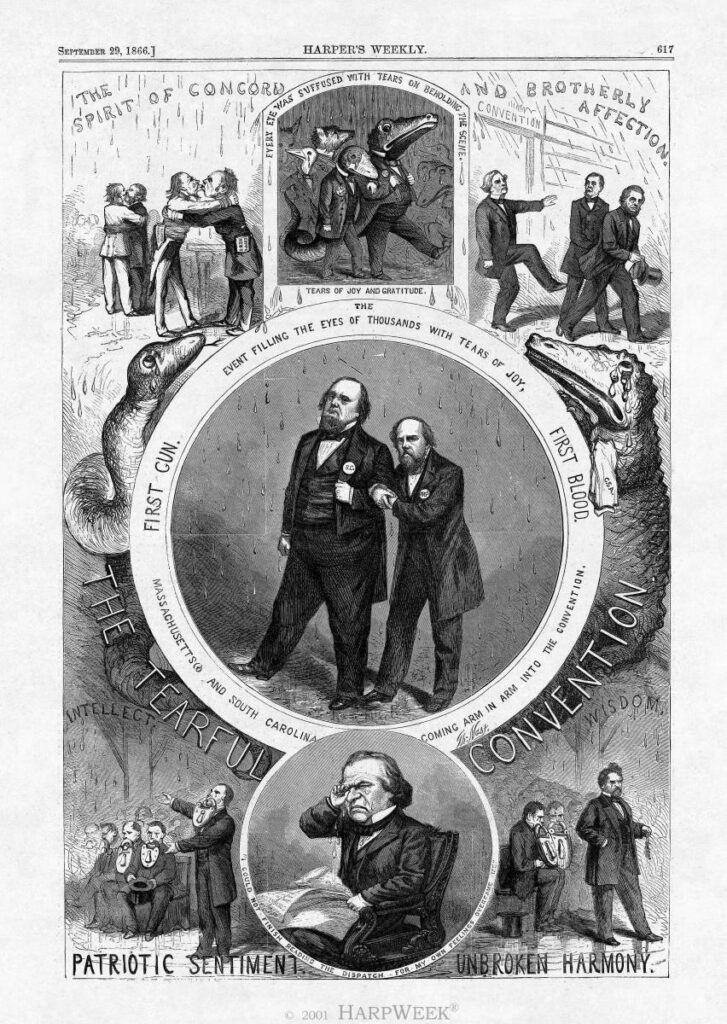

From Harper's Weekly

By 1867 tensions between Johnson and the Republicans in Congress had become a power struggle on the national stage. Congress wrested control of Reconstruction from the president and determined a stricter course for those southern states in which white supremacy still maintained a system akin to slavery. In much of the South, including Georgia, state and local leaders denied freedpeople their civil rights, especially their access to political participation. Congressional reports of blatant southern hostilities to Unionists and northerners in general fueled Republican efforts to design a military plan of reconstructing unrepentant southerners.

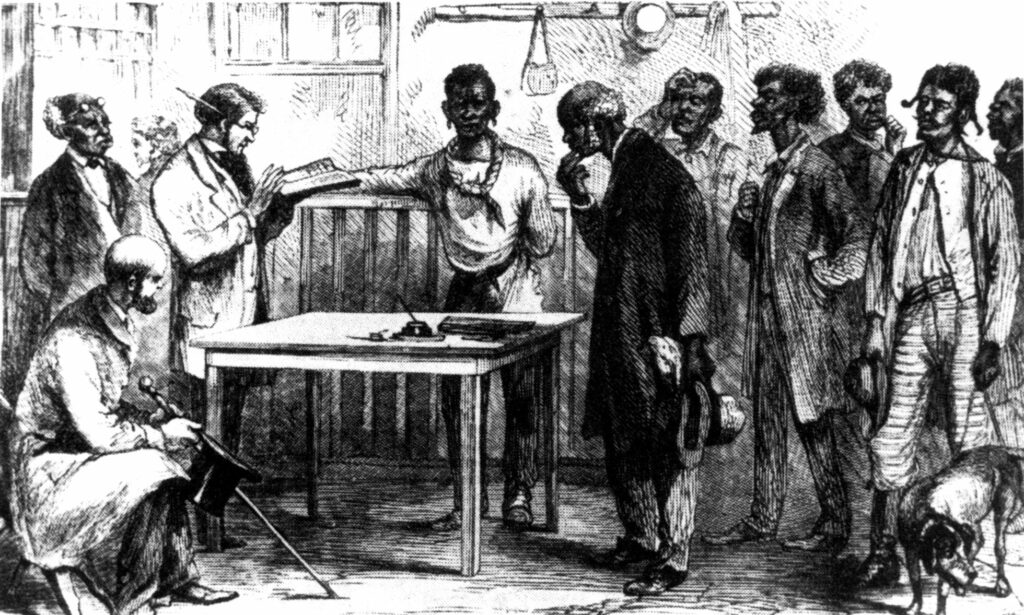

Georgia, now coming under firm military control by the federal government, prepared for another convention in 1867 to comply with the dictates of Congressional Reconstruction. The process of calling this meeting was unusual for the state in a number of respects. First, the military conducted massive voter registrations to include Black males of the same eligibility as white males. Any white males who had ever been disfranchised for disloyalty to the United States could not register. Once this process was complete, eligible voters, Black and white, went to the polls to choose whether or not to hold a convention and, if one was to be held, to select delegates to it. Since many conservative white voters boycotted the polls, first-time Black voters primarily determined the outcome. Blacks voted overwhelmingly in favor of a convention and chose many of the delegates. White conservatives, dissatisfied with the outcome, called their own convention in early December to try and counter Republican momentum. Their efforts failed as the convention, unable to muster enough conservative interest, was thus not representative of the state, with only about half of the counties sending delegates.

From Harper's Weekly

In December 1867 the federally sanctioned convention met in Atlanta and remained assembled until March 1868. Of the 169 delegates, 37 were Black. Republicans, moderate and radical, dominated the convention over the dozen white traditional conservatives. As directed by congressional Reconstruction Acts, the convention proposed a new constitution that included suffrage for Black men. Also in compliance with congressional rules, the document required popular ratification before being implemented as the fundamental law of the state. In April 1868 Georgia voters approved the new constitution and elected a new government.

The Georgia Reconstruction conventions demonstrate the enormous fluidity in the use of conventions to address matters beyond constitution making. The federal mandates imposed upon them also raise questions about the boundaries between national and state sovereignty. Almost a decade later, in the Georgia Constitutional Convention of 1877, the state reasserted its power to conduct and control both the process and the content of its own conventions.