The Andrews Raid of April 12, 1862, brought the first Union soldiers into north Georgia and led to an exciting locomotive chase, the only one of the Civil War (1861-65). The adventure lasted just seven hours, involved about two dozen men, and as a military operation, ended in failure.

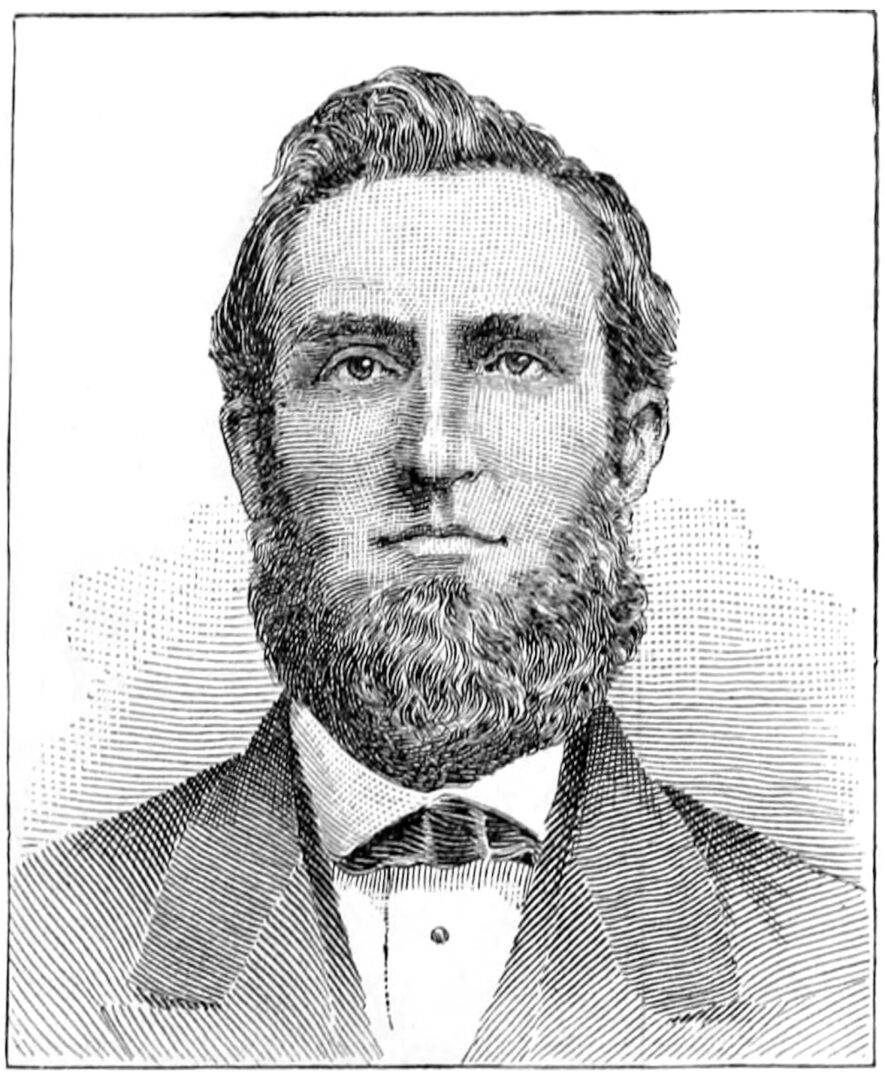

In early spring 1862 Northern forces advanced on Huntsville, Alabama, heading for Chattanooga, Tennessee. Union general Ormsby Mitchel accepted the offer of a civilian spy, James J. Andrews, a contraband merchant and trader between the lines, to lead a raiding party behind Confederate lines to Atlanta, steal a locomotive, and race northward, destroying track, telegraph lines, and maybe bridges toward Chattanooga. The raid thus aimed to knock out the Western and Atlantic Railroad, which supplied Confederate forces at Chattanooga, just as Mitchel’s army advanced.

Image from Internet Archive Book Image

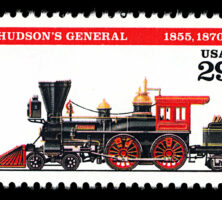

On April 7 Andrews chose twenty-two volunteers from three Ohio infantry regiments, plus one civilian. In plain clothes they slipped through the lines to Chattanooga and entrained to Marietta; two men were caught on the way. Two more overslept on the morning of April 12, when Andrews’s party boarded the northbound train. They traveled eight miles to Big Shanty (present-day Kennesaw), chosen for the train jacking because it had no telegraph. While crew and passengers ate breakfast, the raiders uncoupled most of the cars. At about 6 a.m. they steamed out of Big Shanty aboard the locomotive General, a tender, and three empty boxcars.

Pursuit began immediately, when three railroad men ran after the locomotive, eventually commandeering a platform car. Two of them, Anthony Murphy and William Fuller, persisted in their chase for the next seven hours and more than eighty-seven miles. First suspecting the train thieves to be Confederate deserters, the pursuers acquired a locomotive at Etowah Station. Aware they were being chased, Andrews’s men cut the telegraph lines and pried up rails. Murphy and Fuller switched locomotives—they used three that day—picked up more men, and kept up the chase. The train thieves tried to burn the bridge at the Oostanaula River near Resaca, but the pursuers were too close behind, so close that at Tilton the General could take on only a little water and wood. At about 1 p.m. it ran out of steam two miles north of Ringgold, with the Southerners, aboard the Texas, fast upon them. The Confederates rounded up all the raiders. Only eight of the twenty (Andrews among them) were tried as spies and executed in Atlanta. The rest either escaped or were exchanged.

Though it created a sensation at the time, the Andrews Raid had no military effect. General Mitchel’s forces captured Huntsville on April 11 but did not move on to Chattanooga. The cut telegraph lines and pried rails were quickly repaired. Nevertheless, the train thieves were hailed in the North as heroes. The soldier-raiders received the Medal of Honor; one, Jacob Parrott, was its very first recipient. Neither Andrews nor the other civilian was eligible.

In the postwar years several raiders, notably William Pittenger, published thrilling recollections of their adventures. In Atlanta, William Fuller testily challenged Anthony Murphy over who was in charge of the train pursuit. The escapade made its way into film with Buster Keaton’s silent comedy The General (1927) and Walt Disney’s The Great Locomotive Chase (1956). That a failed historical footnote should kindle such drama fairly attests to the Civil War’s emotional spark.