From 1979 through 1981, a wave of kidnappings and murders terrorized Atlanta’s economically marginalized African American population.

At least twenty-nine Atlantans between the ages of seven and twenty-seven (almost all male) were abducted and slain across a twenty-two-month period. The tragedies—which came to be known as the Atlanta youth murders or, alternatively, the Atlanta child murders—attracted national and international attention, as investigators struggled to solve the cases and placate the city’s increasingly restless poor and working-class Black communities. The racial and class tensions surrounding the murders reflected not only the interracial animosities that had shaped Jim Crow Georgia; they also revealed longstanding intraracial class divides between Black Atlantans.

Courtesy of Special Collections & Archives, Georgia State University Library.

Atlanta grappled with violent crime throughout the 1970s, before the youth slayings even began. The high-profile murder of several white professionals in the city’s central business district had attracted national attention, and local residents were increasingly wary of the city’s troubled downtown. But despite the threats it posed to the city’s profitable convention business, officials struggled to reverse the city’s rates of violent crime. At one point, Atlanta even bore the ignominious distinction of being the nation’s “murder capital.”

It was on the heels of this crime panic that the first victims disappeared. Fourteen-year-old Edward Smith and thirteen-year-old Alfred Evans vanished within days of one another in July 1979, and their bodies were discovered in an isolated area of southwest Atlanta later that month. Following the abduction and murder of several more children in late 1979 and early 1980, family members and acquaintances of the victims founded the Committee to Stop Children’s Murders (STOP). Harnessing organizational and rhetorical strategies honed in the civil rights movement, STOP petitioned the city government to investigate the murders. Nevertheless, authorities hesitated to link the initial cases together, finding “no common denominator” between them. Not until July 17, 1980, did city officials establish a formal investigative task force to solve the killings. By that point—nearly a year after the slayings of Smith and Evans—eleven young Atlantans between the ages of seven and fourteen had already been added to the list of missing and murdered.

Courtesy of Special Collections & Archives, Georgia State University Library.

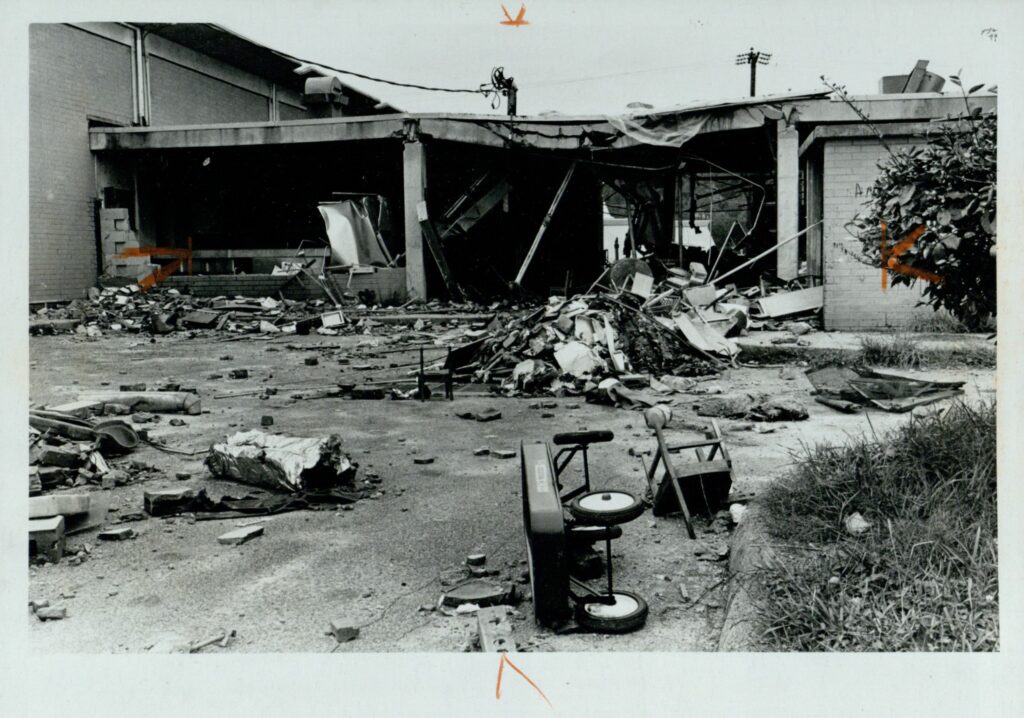

The national media seized upon the Atlanta saga as the death toll continued to climb in the fall of 1980. That October, an explosion at the Gate City Day Nursery in west Atlanta claimed the lives of five people, including four Black children. Though investigators attributed the blast to an overheated boiler, many observers remained unconvinced that it was an accident. Given the broader political climate of intensifying anti-Black racism—marked by a resurgent white power movement—many poor and working-class African Americans in the city worried that a white supremacist individual or organization might be responsible for the killings. Several observers, including the late novelist Toni Cade Bambara, drew parallels between the Gate City tragedy and the 1963 Sixteenth Street Baptist Church bombing—orchestrated by a splinter group of the Ku Klux Klan—which killed four African American girls. Others speculated that the Central Intelligence Agency and Centers for Disease Control (later Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) were executing the murders in the service of a broader eugenicist or exterminationist agenda, a notion that seemed more plausible in the wake of the Tuskegee syphilis experiment.

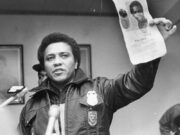

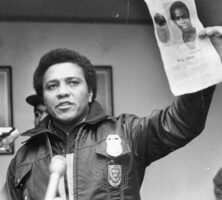

The administration of Maynard Jackson, Atlanta’s first Black mayor, also drew the ire of the city’s poor and working-class Black communities, who accused Jackson of privileging Atlanta’s “business-friendly” reputation over the safety and well-being of its most vulnerable residents. In coordination with white business elites, Atlanta’s Black leaders focused on protecting the city’s image in the wake of the youth murders and on minimizing the potential for civil unrest. Both Jackson and public safety commissioner Lee P. Brown embraced post-racial rhetoric throughout the ordeal, with both men declaring that the tragedy transcended race.

Courtesy of Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

In May 1981 authorities arrested a twenty-three-year-old African American man named Wayne Williams in connection with two of the murders. Williams would eventually be convicted of those murders and implicated in virtually all of the others, effectively ending further investigation of the crimes. The saga’s seemingly hasty resolution—with blame placed entirely at the feet of a single African American culprit—provided a fitting capstone to an investigation governed in large part by the imperatives of the city’s biracial power structure. Some observers, including the family members of several victims, expressed dissatisfaction with the outcome and doubts about William’s guilt. One of STOP’s cofounders, Camille Bell, even sided with Williams during and after his trial, calling him the “thirtieth victim of the Atlanta slayings.”

Questions and conspiracy theories related to the Atlanta youth killings have persisted into the twenty-first century. In the four decades after his conviction, Wayne Williams has continued to maintain his innocence, and the murders have remained a subject of intense public interest, providing the basis for podcasts, academic histories, documentaries, and works of fiction, including Tayari Jones’s acclaimed novel Leaving Atlanta. In light of its enduring hold on the public’s attention, Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms announced in 2019 that local and state authorities would reexamine the case to determine if select pieces of evidence could be subjected to DNA testing.

Courtesy of Special Collections & Archives, Georgia State University Library.