Between 1882 and 1930 the American South experienced an epidemic of fatal mob violence that produced more than 3,000 victims, the vast majority of whom were African Americans. More than 450 documented lynchings occurred in Georgia alone. Lynching refers to the illegal killing of a person by a group of others. It does not refer to the method of killing. Lynching victims were murdered by being hanged, shot, burned, drowned, dismembered, or dragged to death.

Frequency

Georgia’s toll of 458 lynch victims was exceeded only by Mississippi’s toll of 538. During the 1880s and 1890s, instances of lethal mob violence increased steadily, peaking in 1899 when twenty-seven Georgians fell victim to lynch mobs. Between 1890 and 1900 Georgia averaged more than one mob killing per month.

The frequency of mob violence declined somewhat in the first decade of the twentieth century, but by 1911 lynch mobs again were active, killing nineteen Georgians. After another peak year in 1919, the trend of violence was distinctly downward, and in three years (1927-29) no victims were reported. Although later years would see lynch violence recurring sporadically, the heyday of the lynch mob in Georgia was over by 1930.

The Victims

Of Georgia’s victims of lynch mob “justice,” the overwhelming majority (95 percent) were Black, and they were murdered primarily, although not exclusively, by white mobs. There is some evidence that 12 of the 435 African American victims were murdered by Black or mixed-race mobs. There is also evidence that less than 5 percent of Georgia’s victims were white, but none of those were victims of Black mobs. Georgia’s lynch violence almost always consisted of white mobs killing Black men.

According to newspaper accounts, the most common justification for mob violence was the alleged murder of a white person. The second most frequent justification was the purported rape or attempted rape of a white woman. While alleged violations of criminal law (murder, rape, arson, burglary, assault) were the most common reasons mob members gave for their actions, in some instances lynch victims were accused of race crimes, that is, of violations of the racial code of conduct that governed social relations between Blacks and whites during the era of Jim Crow segregation.

The case of Eli Cooper is illustrative. One night in late summer 1919, a gang of fifteen or twenty white men abducted Cooper, a Black man, from his home in Cadwell in Laurens County and transported him to Petway’s Gift Church in Dodge County, a few miles away. The gang shot Cooper, set the church on fire, and pitched his body into the flames. According to the Atlanta Constitution, Cooper’s transgression was in speaking out against racial discrimination. The paper reported on August 29, 1919, that he had been “talking considerably of late in a manner offensive to the white people.” The paper further reported, “The white residents were informed that an uprising of negroes was set” for late September and “Cooper’s own remarks, it is alleged, were . . . that the negroes had been 'run over for fifty years, but this will all change in thirty days.'” Apparently, many whites in Cooper’s community were concerned about the possibility of an “uprising,” which could threaten the social order.

Geographical Distribution

Lynch-mob violence occurred statewide, with at least one lynching documented in the vast majority of Georgia’s counties. Mob violence was somewhat concentrated across middle and south Georgia, especially in the southwestern corner of the state, where Decatur County witnessed the most lynching activity—thirteen incidents. As a form of social control, lynchings may have been more common in rural areas that were dependent upon a Black labor force, especially the cotton-producing counties in the central part of the state and the expanding lumber and forest-products areas in the southwest. It has also been suggested that mob violence was more frequent in locales where social change was threatening to alter traditional relations between Blacks and whites.

Lynchings were less common in northeast Georgia and along the coast. The bloodiest episode in the state’s lynching history, however, took place in Watkinsville on June 29, 1905, when a mob invaded the Oconee County jail and forcibly removed eight inmates, seven Black men and one white man. The mob tied the men to fence posts and riddled their bodies with bullets; no one was ever charged in the killings.

Notorious Lynchings

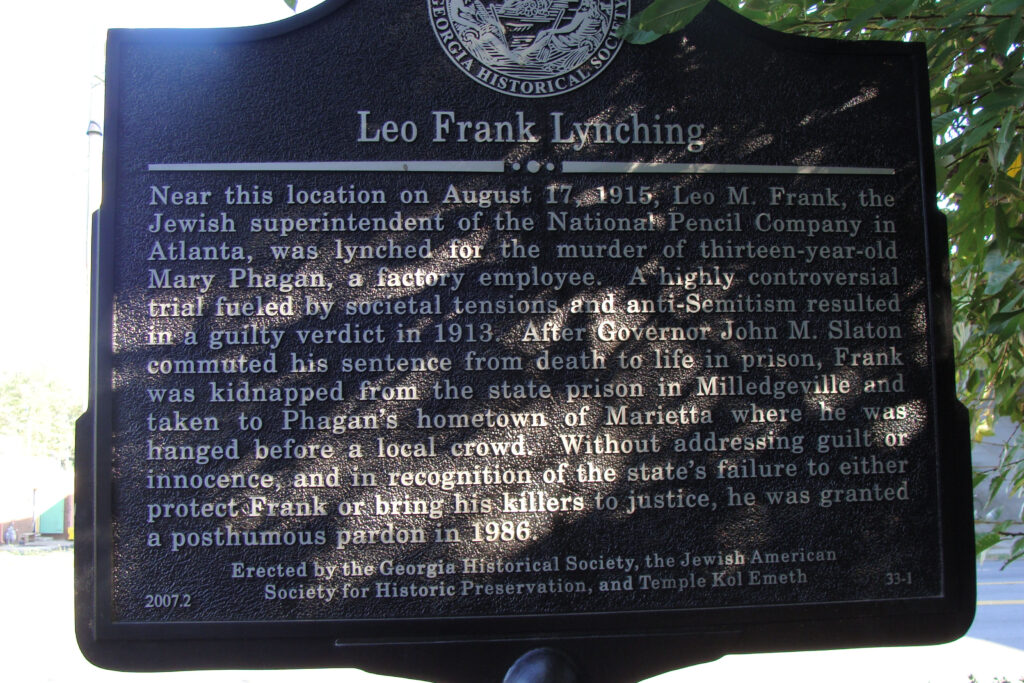

All lynchings had a devastating impact on the families, friends, and communities of the victims. Several particular incidents, however, received significant media attention as a result of their brutality. Leo Frank, for example, a Jewish factory superintendent accused of killing a young girl in Atlanta, was one of the relatively few white victims of lynch-mob “justice” in the state. His lynching in 1915 brought unwelcome national and international scrutiny to Georgia. Three other particularly violent incidents—the lynching of Sam Hose, the lynchings of Mary Turner and her unborn baby, and the multiple lynchings at Moore’s Ford—also gained widespread notoriety.

Courtesy of Georgia Historical Society.

Sam Hose

Although most lynchings were simple executions in which the victim was hanged or shot to death, some were accompanied by spectacle and grotesque torture. Arguably one of the best known of the latter was the torture murder of Sam Hose (a.k.a. Sam Holt) near Newnan in Coweta County on Sunday afternoon, April 23, 1899. Hose was in jail, charged with murdering a white man. An unmasked mob advanced on the jail and took Hose to a site about a mile away. They tied him to a small pine tree, cut off his ears, and mutilated his body with knife cuts. The mob then doused him with oil and set him on fire; his body convulsed, and his veins burst. The Atlanta Constitution estimated that 2,000 people witnessed this torture killing, many of whom traveled from Atlanta on two special trains after hearing of Hose’s capture and eminent lynching. From the cooling ashes, spectators took pieces of bone and bits of flesh, along with remnants of the pine sapling, as souvenirs. For those who could not attend, the Constitution devoted the first two pages of Monday’s newspaper to describing the grisly details.

Mary Turner

On May 16, 1918, Sidney Johnson, a Black man, shot and killed his employer Hampton Smith, a white Brooks County farmer known for cruelty to his workers. After Johnson fled the crime scene, a mob-led manhunt scoured the county for him and others suspected to be involved in the murder. On May 18 the mob found and lynched one of these suspects, Hayes Turner.

Turner’s wife, Mary Turner, publicly objected to her husband’s murder and threatened to seek warrants for the arrest of those responsible. Her remarks enraged locals. Eight months pregnant at the time, she was caught on May 19 by the white mob. They hung Turner by her ankles from a tree, used gasoline to burn off her clothes, and cut open her stomach. The unborn baby fell to the ground, where it was reportedly killed by members of the mob. The mob hastily buried Turner later that night.

At least eleven people total were killed by the Brooks County mob over about two weeks. Johnson was killed in a shootout with police three days after Mary Turner’s murder. While Turner’s lynching engendered silence locally—nobody was ever charged in connection with the week’s violence—it led to a national outcry. Her story was the centerpiece of the Anti-Lynching Crusaders’ campaign for the Dyer Bill, which classified lynching as a felony and was defeated by filibuster in the U.S. Senate in 1924. In 2010 a historical marker was erected near the site of Turner’s lynching.

Moore’s Ford

The last mass lynching in Georgia—and for that matter, in the country—took place on July 25, 1946. Two young Black couples who worked as sharecroppers, Roger and Dorothy Malcom and George and Mae Murray Dorsey, were taken by an unmasked mob to the Moore’s Ford Bridge, on the Apalachee River at the border of Walton and Oconee counties. The couples were beaten and shot multiple times. This lynching was significant not only because of the number of victims but also because the crime was reported in national newspapers and led to mass rallies in New York City and Washington, D.C. Georgia governor Ellis Arnall requested assistance from the Georgia Bureau of Investigation in finding the members of the lynch mob, and a few days after the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People asked U.S. president Harry S. Truman to investigate, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) entered the case. Despite these investigations, no indictments were ever returned.

The Moore’s Ford lynching added fuel to the fire of civil rights activism, inspired a renewed call for federal anti-lynching legislation in Congress, and helped stir Truman to create the President’s Committee on Civil Rights. Despite the reduced tolerance for lynching in the South after 1930 and increasing opposition to mob violence outside the South, anti-lynching legislation never materialized. In 1999 the Moore’s Ford Memorial Committee and the Georgia Historical Society erected a historical marker commemorating the 1946 lynching. It is believed to be the first official marker for a lynching in Georgia.

In April 2006 the FBI announced that it would review its 1946 investigation of the crime.

Lynching in Literature

Much of the literature on southern lynching—in both fictional and nonfictional form—has come from Georgians. Novels by four prominent writers are built around the community dynamics of racial tension and lynch mobs, all set in fictional small-town or rural Georgia. These include Walter White’s Fire in the Flint (1924), loosely based on his own investigations of mob violence in south Georgia; Trouble in July (1940), by Erskine Caldwell, who also wrote several short stories in the 1930s dealing with lynching incidents; Lillian Smith’s first and most controversial novel, Strange Fruit (1944); and The Hawk and the Sun (1955), one of two novels written by poet Byron Herbert Reece. The Leo Frank case has inspired several fictional interpretations, including a novel by David Mamet, The Old Religion (1997), and a Broadway musical, Parade (1999), by playwright Alfred Uhry.

Two of the more influential nonfictional analyses of the causes, patterns, and rates of southern lynchings were Walter White’s Rope and Faggot (1929) and Arthur F. Raper’s The Tragedy of Lynching (1933). Both were based on the authors’ firsthand investigations of incidents in Georgia and beyond.