On June 27, 1864, Kennesaw Mountain, located about twenty miles northwest of Atlanta in Cobb County, became the scene for one of the Atlanta campaign’s major actions in the Civil War (1861-65).

Beginning of the Atlanta Campaign

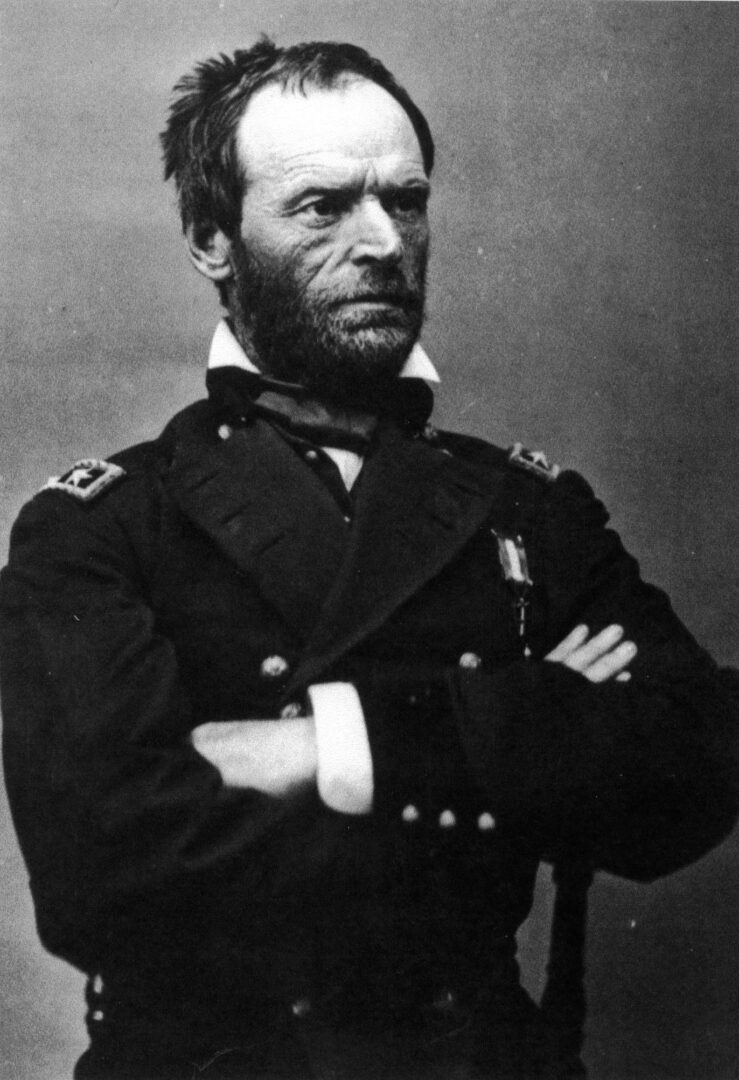

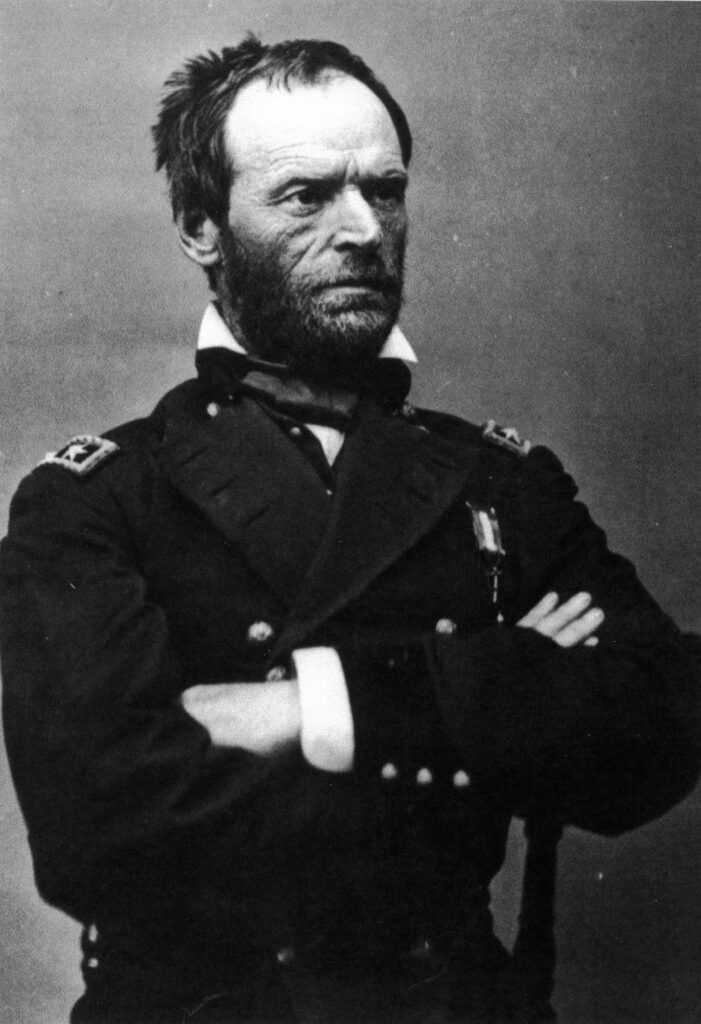

One month earlier, Union major general William T. Sherman led a force of three armies from Chattanooga, Tennessee, into Georgia. His objective was the destruction of Confederate general Joseph E. Johnston’s Army of Tennessee. Johnston hoped to prevent his army’s annihilation while protecting his supply and communications center at Atlanta. He frustrated Sherman by conducting a masterful defensive strategy, entrenching his army across Sherman’s path and forcing the Union armies into either a frontal assault or a flanking maneuver against well-prepared field troops. Johnston was ever alert for an opportunity to strike at isolated units of the Union army but was primarily concerned with keeping his own army together as a cohesive fighting force and blocking Sherman’s push into Atlanta.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Even though Sherman continued to force the Confederates backward by skirting their positions, he worried that his inability to destroy Johnston’s army would allow the Confederate government to transfer troops, bolstering Confederate general Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia against the Union’s spring offensive in Virginia. These fears were allayed at Kennesaw Mountain in late June, where Sherman believed that his opponent had finally made a mistake and that a well-executed attack could crush the Army of Tennessee and open the way to Atlanta.

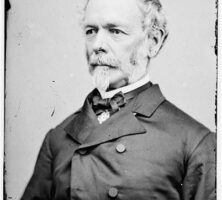

By June 19 Johnston had established a strong defensive line along Kennesaw Mountain. Sherman attempted to bypass the formidable position to the south, but a Confederate counterattack at Kolb’s Farm on June 22 thwarted his move. Although the counterattack did not inflict serious casualties, it forced Sherman into either swinging his army wider to the south in order to bypass the Confederate position or attacking Confederate entrenchments. Surprisingly, Sherman chose to attack. He reasoned that by blocking the Union advance at Kolb’s Farm, the Confederates had overextended their lines. Indeed, the Confederates were arranged in a large semicircle that stretched eight miles from Kolb’s Farm in the south to Kennesaw Mountain in the north. Sherman concluded that a strike at the Confederate center would break its line and give him the advantage needed to destroy Johnston’s entire army.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

For Sherman’s plan to succeed, the Union army would need to do three things: confuse Johnston by feigning attacks on each end of the Confederate line, forcing him to pull men away from the center; launch a diversionary attack at Kennesaw Mountain itself to probe for weaknesses and tie down the Confederates; and attack two key points in the Confederate center to break the army’s overextended line. The first would capture Pigeon Hill just south of Kennesaw Mountain, while a larger assault would overrun a wooded ridge further to the south (known today as Cheatham Hill in honor of Confederate major general Benjamin Franklin Cheatham, whose Tennesseans defended the hill).

Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration.

Battle on Kennesaw Mountain

Sherman’s troops bombarded the Confederate positions at nine o’clock on the morning of June 27 and then advanced along the base of Kennesaw Mountain. The Confederates easily repulsed this diversionary attack. Meanwhile, rough terrain and a stubborn defense stymied the Union assault at Pigeon Hill, which sputtered out after a couple of hours. At Cheatham Hill, the heaviest fighting occurred along a salient stretch in the Confederate line dubbed “Dead Angle” by Confederate defenders. Union troops made a desperate effort to storm the Confederate trenches. However, as elsewhere, the rough terrain and intense Confederate fire combined to defeat the Union army. Within hours, the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain was over. Union casualties numbered some 3,000 men while the Confederates lost 1,000, making it one of the bloodiest single days in the campaign for Atlanta.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

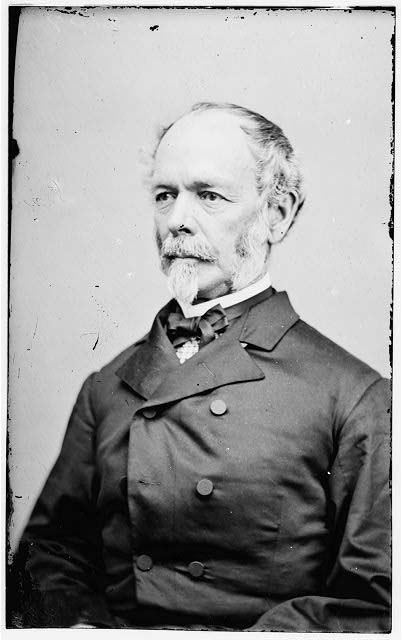

Sherman hated to admit failure, and his pride led him to consider renewing the assault. However, his subordinates, especially General George H. Thomas, convinced him to reconsider such a hopeless endeavor. After several days of scouting and preparation, Sherman again flanked the Confederate lines. The ever-vigilant Johnston, however, abandoned his entrenchments on July 2 and deftly blocked the Union advance again at Smyrna. The war of maneuver continued. Although a tactical defeat for Sherman, the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain did not prevent his continued drive toward Atlanta. Strategically, Sherman still had the initiative, and more importantly, he had the men, the materiel, and the will to continue pressing Johnston’s beleaguered force.

Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield

Today, visitors can explore this battlefield, thanks in part to the foresight of Lansing J. Dawdy, an Illinois veteran of the battle. In 1899 Dawdy purchased sixty acres of land near the Dead Angle. The property was transferred in 1904 to the Kennesaw Mountain Battlefield Association. In 1914, to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the battle, the organization erected a monument dedicated to the Illinois soldiers who fell in the assault on Cheatham Hill. However, unable to restore the battlefield as planned, the association transferred ownership of the property to the federal government in 1916, and the next year Congress authorized the Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield site.

The park itself was not formed until 1935. Since then, it has grown to nearly 3,000 acres. The first park facilities, roads, and trails were built during the 1930s and 1940s. Although new development continued gradually over the next fifty years, today the park focuses most of its resources on maintaining existing facilities rather than planning any new construction. The number of guests who visit the park each year has climbed steadily from around 4,700 in 1939 to 1.4 million in 2004. (The number of visitors reached a peak in 1983, with 2.45 million visitors.) Part of the reason for this tremendous growth is that the park remains the largest wilderness area in the metropolitan Atlanta area.

Unfortunately, this heavy visitation comes with a cost. In 2005 the park was named one of the Civil War Preservation Trust’s “Ten Most Endangered” battlefields, due primarily to the impact of urban sprawl and traffic congestion.