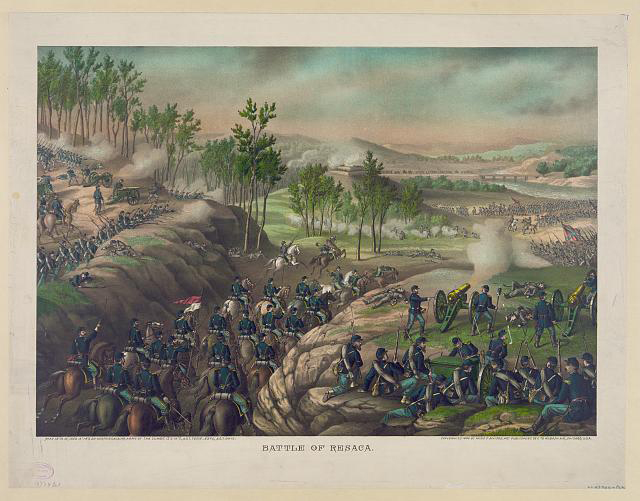

Fought on May 14-15, 1864, the Battle of Resaca was the first major engagement of the Atlanta campaign in the Civil War (1861-1865). Situated on the north bank of the Oostanaula River approximately seventy-five miles northwest of Atlanta, Resaca was located on the strategically important Western and Atlantic Railroad. The fighting at Resaca demonstrated that the outnumbered Confederate army could only slow but not stop the advance of Union forces into Georgia.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Prelude to Resaca

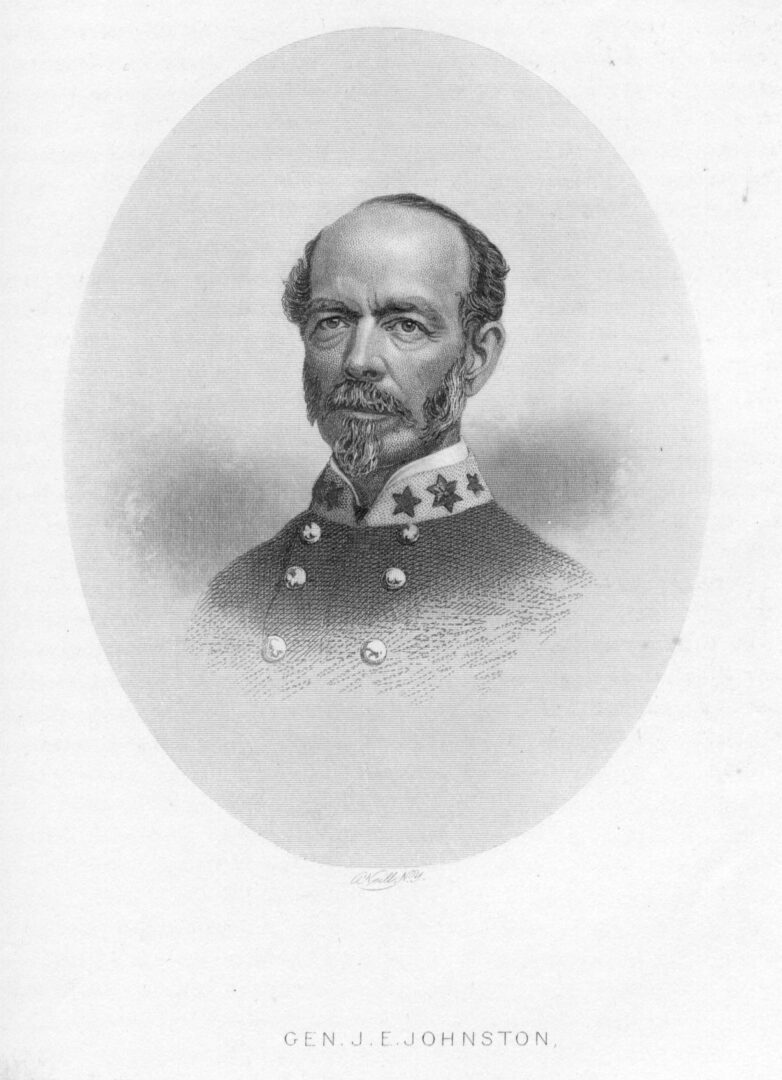

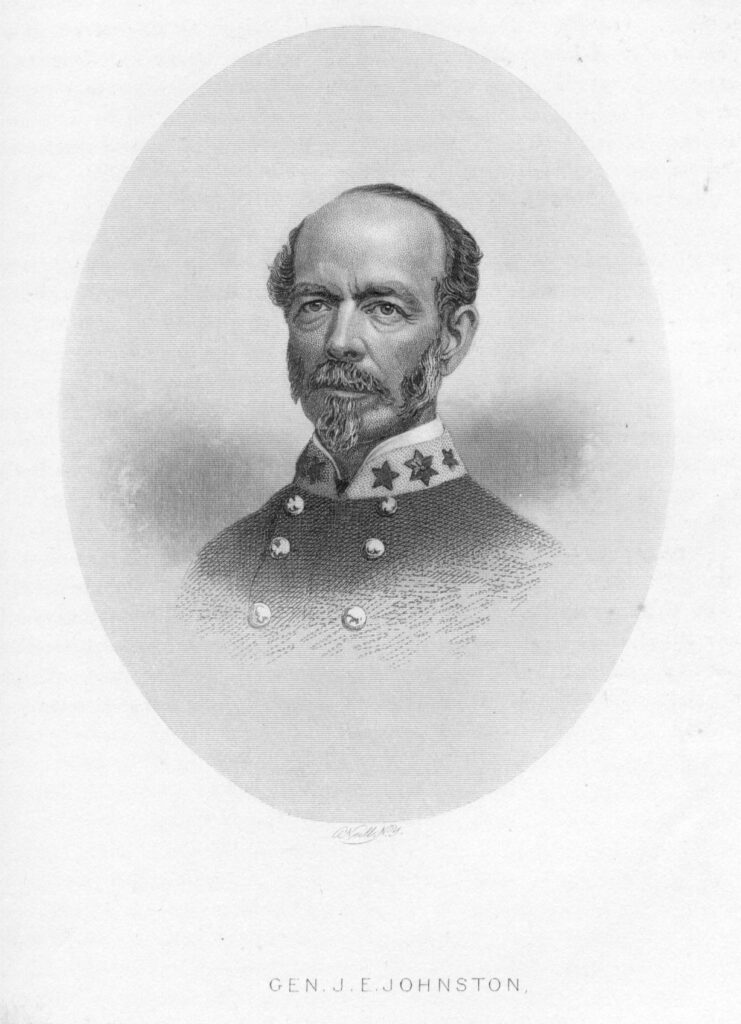

Following its November 1863 defeat at Chattanooga, Tennessee, the Confederate Army of Tennessee retreated thirty miles to the southeast and encamped in Dalton, Georgia, for the winter. General Joseph E. Johnston assumed command of the demoralized Confederate troops and began preparations for a defensive struggle in the spring. Johnston entrenched his men in Dalton and along Rocky Face Ridge, a steep and rugged ridgeline on the outskirts of the town.

In early May 1864 Union major general William T. Sherman opened the Atlanta campaign by moving south from Chattanooga with 110,000 troops. Sherman’s forces consisted of three separate army groups: the Army of the Cumberland, under the command of George H. Thomas; the Army of the Tennessee, led by James B. McPherson; and the Army of the Ohio, commanded by John M. Schofield. Confederate forces were outnumbered approximately two to one, but the last-minute arrival of reinforcements led by Major General Leonidas Polk increased Johnston’s army to almost 70,000 men.

From The History of the State of Georgia, by I. W. Avery

The first skirmish of the campaign occurred on May 7, when Union forces swept Confederate cavalry from Tunnel Hill, a small promontory in front of Rocky Face Ridge. Sherman then lined up his armies facing the ridgeline, and over the next two days he launched a number of small-scale attacks against the heavily fortified Confederate position. In the bloodiest of these encounters, Union soldiers fought their way up Rocky Face Ridge while Confederate defenders rolled large rocks down upon the attackers. The Confederate position proved impregnable.

However, the Union demonstrations against Rocky Face Ridge were merely a diversion, for Sherman had no intention of launching a full frontal assault against the well-entrenched Confederates. With General Johnston’s attention focused on the Union forces to his front, Sherman sent McPherson’s 25,000-man Army of the Tennessee on a covert march south to Snake Creek Gap. The unguarded road through Snake Creek Gap led to the village of Resaca, some dozen miles south of Dalton. If McPherson could capture Resaca, then the Confederate supply line would be severed, and Johnston’s army would be trapped. On the night of May 8-9, McPherson’s army passed through the gap and emerged behind the Confederate front lines. Upon learning the news, a jubilant Sherman exclaimed, “I’ve got Joe Johnston dead!”

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Sherman’s elation proved premature, however, for McPherson proceeded with extreme caution and failed to seize Resaca. As Sherman sent more troops south to Snake Creek Gap, Johnston realized that he was being outflanked. On the night of May 12-13, he evacuated Rocky Face Ridge and the town of Dalton and marched his men south, where by the following morning they had taken up defensive positions along a four-mile front to the west and north of Resaca. The Confederates had shifted positions just in time to meet the arrival of Sherman’s forces. Throughout the day on May 13, Union and Confederate troops fought a number of skirmishes, but the day ended before the Union armies were fully deployed for battle.

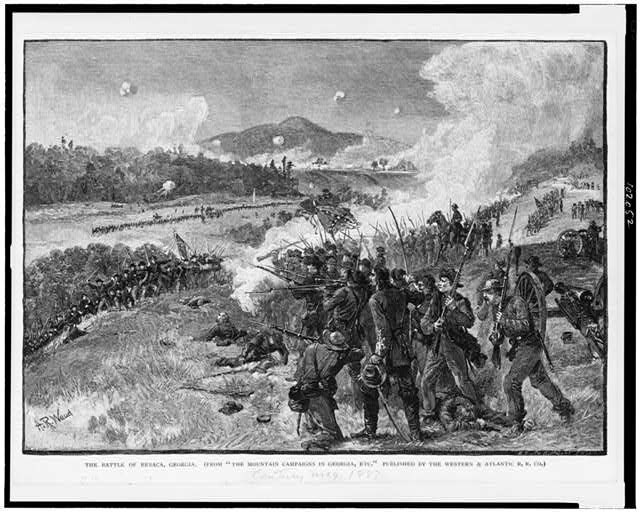

The Battle of Resaca

On Saturday, May 14, the fighting at Resaca escalated into a full-scale battle. Beginning at dawn, Union forces engaged the Confederates along the entire four-mile front. In the early afternoon Schofield’s Army of the Ohio attacked the sharply angled center of the Confederate line. The assault was badly managed and disorganized, in part because one of Schofield’s division commanders was drunk. As the Union attack unraveled and became a fiasco, Johnston launched a counterattack on Sherman’s left flank. The counterattack collapsed, however, in the face of a determined stand by a Union artillery battery. In the evening Union forces pushed forward and seized the high ground west of Resaca, which placed the bridges leading south from the town within artillery range and threatened Johnston’s line of retreat.

Courtesy of Historic Preservation Division, Georgia Department of Community Affairs.

The following day Sherman renewed his assault on the Confederate center. In order to fire on the advancing Union troops, Captain Max Van Den Corput’s artillery battery assumed an advanced position some eighty yards in front of the main Confederate line. The four-gun Confederate battery, protected behind an earthen parapet, became the center of a furious struggle. Union troops massed in a ravine directly in front of the battery, and the 70th Indiana Regiment, led by Colonel Benjamin Harrison (the future U.S. president), swarmed over the parapet and overwhelmed the Confederate gunners. However, Harrison’s men were exposed to withering fire from the main Confederate line and had to take cover. For the rest of the day the abandoned guns sat in a deadly no man’s land. After the sun set, Union soldiers dug through the parapet, slipped ropes around the four cannons, and dragged them back to the Union lines.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

As the fighting raged on May 15, Johnston learned that a division of Union troops had crossed the Oostanaula River southwest of Resaca. Sherman had once again taken advantage of his numeric superiority to outflank the entrenched Confederates. Johnston’s position had thus become untenable, and during the night his troops abandoned their defenses and retreated farther south. The Battle of Resaca demonstrated that the Atlanta Campaign would be hard fought and bloody. Johnston’s army had suffered some 2,800 casualties, and Union losses were at least as high. But Sherman, with his superior forces, could continue pressing and outflanking the Confederate army, driving it farther south and ever closer to Atlanta.

State Historic Site

Resaca’s Confederate Cemetery, which contains the graves of more than 450 Confederates killed in the fighting at Resaca, was dedicated in 1866. For nearly a century the battlefield—an area of privately owned farms, pastures, and wooded hills—remained relatively undisturbed. In 1960 the construction of Interstate 75 significantly altered the local landscape, destroying approximately one-half mile of Confederate earthworks.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

Beginning in 1994 the Friends of Resaca Battlefield—a nonprofit organization dedicated to battlefield preservation—began lobbying the state of Georgia to purchase and protect the remaining portions of the battlefield. In 2000 the Georgia Civil War Commission helped facilitate the state’s purchase of a tract of farmland containing more than 500 acres, which included remnants of original entrenchments, in Gordon and Whitfield counties. In 2008 the Georgia Department of Natural Resources broke ground on the Resaca Battlefield State Historic Site, which is scheduled to include a museum, a welcome center, a theater showing an interpretive film, and marked trails.