More than 3,500 Black Georgians served in the Union army and navy between 1862 and 1865. Enlistment occurred in two distinct phases, beginning on the federally occupied Sea Islands of Georgia and South Carolina in 1862-63, and resuming in northwestern Georgia and southern Tennessee in mid-1864, during the latter stages of the Atlanta campaign.

Recruitment on the Sea Islands

The arrival of Union warships prompted Confederate forces to evacuate Georgia’s coastal islands during February and March 1862. With the surrender of Fort Pulaski in the Savannah harbor on April 11, the state’s coast fell under Northern control, and enslaved Georgians began making their way to Union lines. On April 7, 1862, Abraham Murchison, a Savannah preacher who escaped from slavery in Savannah, helped recruit 150 formerly enslaved men for a Black regiment being organized by General David Hunter at Hilton Head, South Carolina. Hunter disbanded the regiment in August of that year, but a company of thirty-eight men was sent to St. Simons Island, Georgia, where they helped other Black escapees defend themselves against Confederate attack.

In 1862 Union authorities began to authorize Black enlistment. The St. Simons detachment, together with a group of thirty to forty additional Georgia recruits, joined the army as Company A of the First South Carolina Volunteers. Formerly enslaved men from St. Simons also composed the bulk of Company E, and Georgia recruits could be found in smaller groups scattered throughout the regiment. In June 1863 a special draft for the Third South Carolina Volunteers was held on Ossabaw Island and at Fort Pulaski, Georgia, as well as at Fernandina Beach, Florida, near Georgia’s southern border. This regiment, which was soon consolidated with the embryonic Fourth and Fifth South Carolina Volunteers to form the Twenty-first U.S. Colored Infantry (USCI), numbered slightly more than 300 men until December 1864, when its ranks were filled by freedmen who had followed Union general William T. Sherman to Savannah.

Enlistment in the Interior

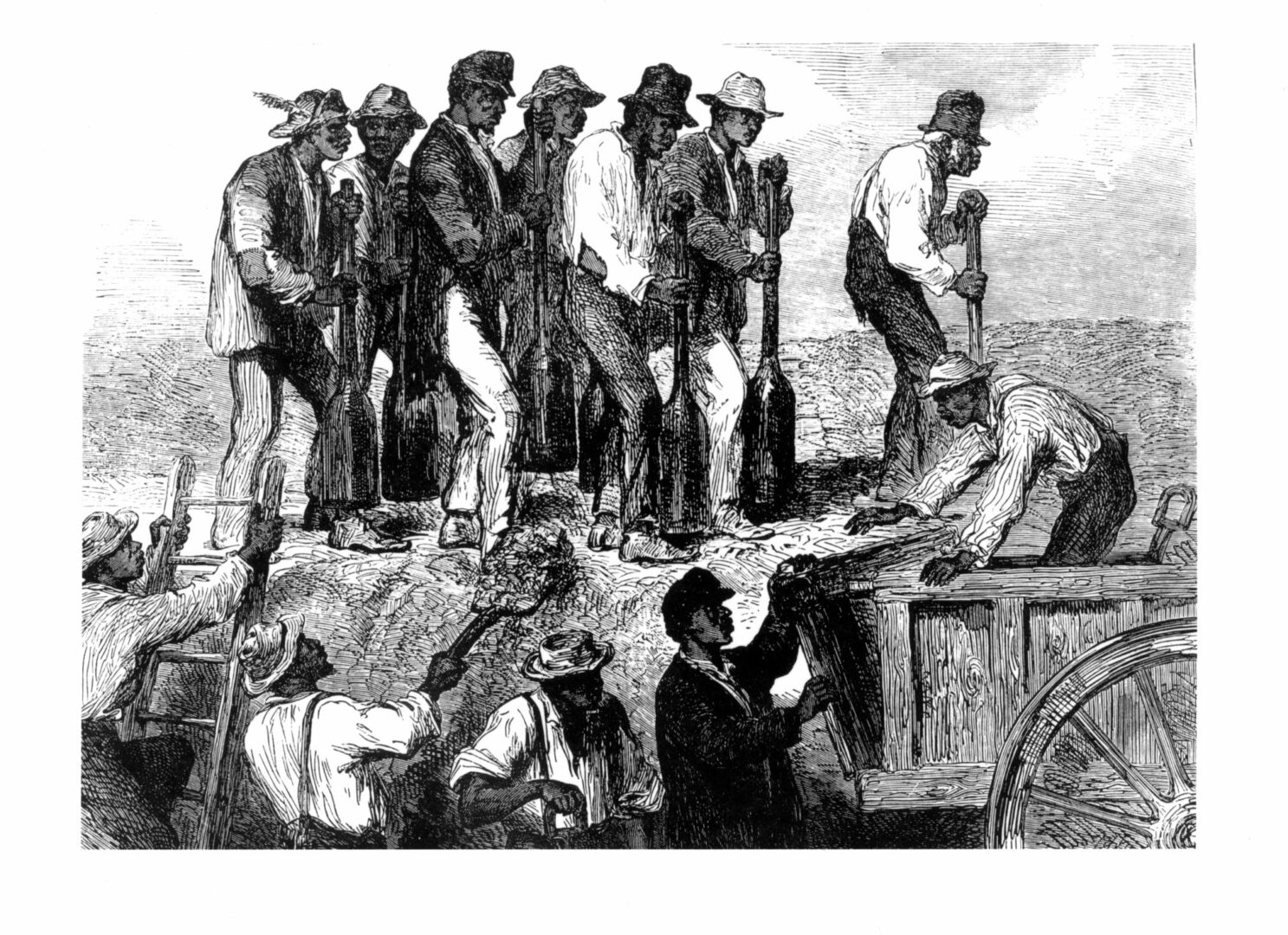

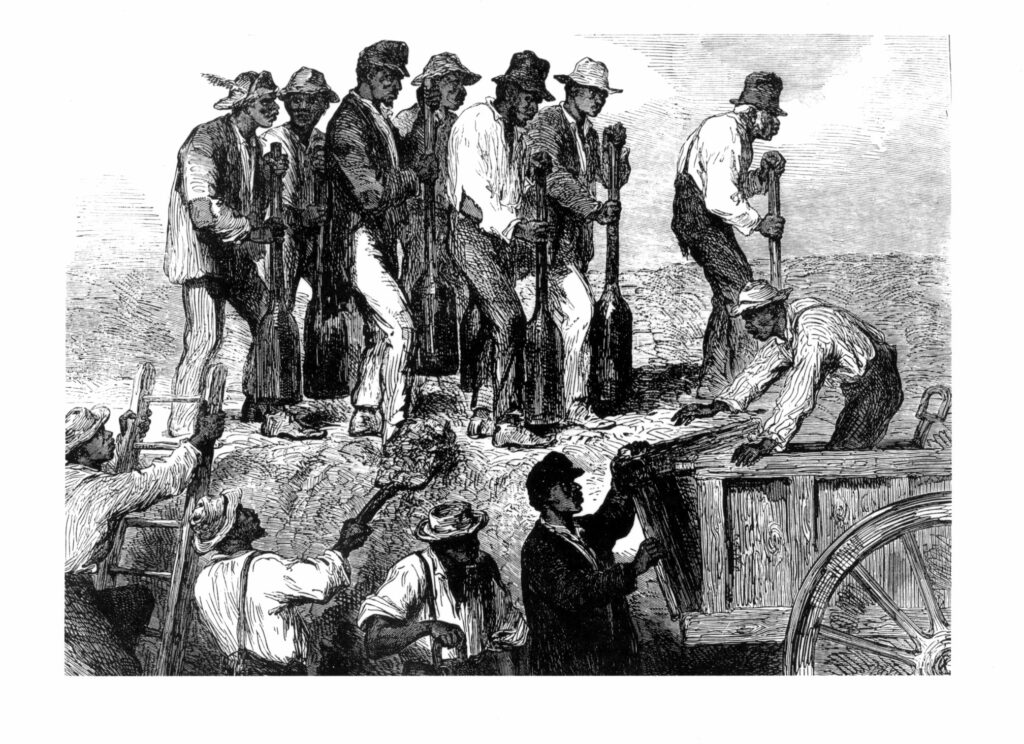

During the Atlanta campaign of May-September 1864, General Sherman opposed Black enlistment with word and deed. An avowed white supremacist and a reluctant liberator at best, Sherman made no effort to conceal his contempt for African Americans or to disguise the racist dogma behind his opposition to Black soldiers. Such phrases as “niggers and vagabonds,” “niggers and bought recruits,” and “niggers and the refuse of the South” filled his personal letters. Anxious to employ Black workers as laborers, Sherman was determined that the forces under his command would remain exclusively white. On June 3, 1864, he issued Special Field Order No. 16 forbidding recruiting officers to enlist Black soldiers who were employed by the army in any capacity.

Despite Sherman’s opposition, the enrollment of Black soldiers began in occupied areas of northwestern Georgia under authority granted to Colonel Ruben D. Mussey, the Nashville, Tennessee-based commissioner for the Organization of U.S. Colored Troops in the Department of the Cumberland. Most activity took place between July and September 1864, when the Forty-fourth U.S. Colored Infantry was stationed in Rome, Georgia, for recruiting purposes. By late summer the Forty-fourth USCI contained some 800 Black enlisted men and was commanded by Colonel Lewis Johnson, who was white. Approximately three-fourths of these Black soldiers were doing garrison duty in Dalton on the morning of October 13 when advance units of the 40,000-man Army of Tennessee, commanded by Confederate general John Bell Hood, converged unexpectedly upon the little village, cutting off all avenues of retreat. Initial skirmishing between Black troops and Rebels left several Confederates dead and their comrades “over anxious to move upon the 'niggers,'” as reported to Johnson. Hood vowed to take no prisoners if the Union defenses were carried by assault and later added that he “could not restrain his men and would not if he could.”

Although Johnson claimed that his Black troops displayed the “greatest anxiety to fight,” he surrendered to Hood and quickly secured paroles for himself and the 150 or so other white troops attached to the garrison. The regiment’s 600 African American enlisted men suffered a harsher fate. Some were reenslaved, while others were sent to work on fortification projects in Alabama and Mississippi. Many ended the war as prisoners in Columbus and Griffin, Georgia, where they were released during May 1865 in what one of them described as a “sick, broken down, naked, and starved” condition. Fearful of reprisals from embittered Confederates, the Black veterans concealed their connection with the Union cause.

Additional Black enlistment took place along the Georgia coast in 1865 after the fall of Savannah and Sherman’s departure into South Carolina. Many Black Georgians from coastal counties also saw service as pilots and seamen on Union vessels throughout the war.