On January 24, 1987, over 15,000 civil rights activists participated in the Brotherhood March, which focused national attention on Forsyth County’s reputation for racial intolerance and violence. A week prior to this march, on January 17, white supremacists had violently obstructed another civil rights demonstration.

First March

As a recent transplant to the region, Charles Blackburn may not have fully understood the depth of local racial animosity when he announced plans for a “brotherhood walk” to demonstrate racial progress in early 1987. Forsyth had been an all-white county since 1912, when local whites forcibly expelled more than one thousand Black residents following the rape and murder of a young white woman. The county remained unsafe even for Black travelers in the decades that followed, and the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) maintained an active presence in local affairs. So it came as little surprise then when Blackburn abandoned his plans due to threats and intimidation.

In Blackburn’s place, two new leaders stepped forward to organize the march: Dean Carter, a white resident of nearby Gainesville, and Hosea Williams, a veteran civil rights activist and Atlanta city councilman. Williams and Carter confirmed that the march would take place as planned on January 17—the Saturday before the Martin Luther King Jr. holiday. In response, local white supremacists announced the creation of the Forsyth County Defense League and tapped J.B. Stoner, a convicted church bomber, to address a “White Power Rally” scheduled for the same afternoon.

When a chartered bus carrying some seventy-five marchers arrived at the designated starting point at the corner of State Highway 9 and Bethelview Road, hundreds of white supremacists were waiting. Less than a mile into the march, the white mob broke through the undermanned police lines and surrounded the interracial activists, creating a potentially deadly situation. At the behest of Forsyth County sheriff Wesley Walraven Jr., the organizers called off the remainder of the march amid a hail of rocks, bottles, and bricks.

Second March

The march received extensive media coverage, featuring prominently in the pages of national dailies. The Los Angeles Times announced: “Klan Group Stones Marchers in All-White County of Georgia.” A photo on the front page of the Boston Globe depicted outnumbered riot police dragging a white supremacist from the road. Determined to march again the following Saturday, Williams quickly mobilized a network of civil rights activists from his previous position with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC).

On the morning of January 24, thousands of marchers were waiting to take part in the protest, forcing Williams and other organizers to locate additional buses. Though many were left behind for lack of transportation, an estimated 15,000 to 20,000 protestors walked the same route as the previous weekend’s march.

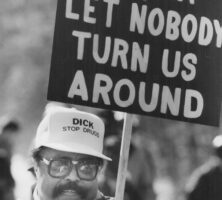

After reaching the courthouse, leaders called for an end to racial exclusion in Forsyth County. Speakers included Hosea Williams, Coretta Scott King, Atlanta mayor Andrew Young, and comedian Dick Gregory. Other notable marchers included U.S. congressman John Lewis; Senators Sam Nunn and Wyche Fowler; Reverends Jesse Jackson and Ralph David Abernathy; and NAACP executive director Benjamin Hooks.

Chastened by the previous week’s violence, Governor Joe Frank Harris activated nearly 2,500 law enforcement officers and members of the Georgia National Guard. Infamous white supremacists such as David Duke and J.B. Stoner unsuccessfully attempted to disrupt the march, and Duke was arrested for attempting to block a road.

Aftermath

The march resulted in litigation that hastened the financial ruin of the KKK in Georgia. In McKinney v. Southern White Knights (1988), the January 17 marchers won a $1,000,000 verdict. The court forced the Invisible Empire, a group affiliated with the Klan, to forfeit their assets and dissolve; their office equipment was later distributed to NAACP community offices.

The international media spotlight, including a special edition of the fledgling Oprah Winfrey Show, resulted in the Mead Corporation cancelling plans to open a factory in the county and spurred the establishment of a committee to foster integration in Forsyth County. Although little change came from the committee’s recommendations, Forsyth County diversified in the years ahead, becoming one of the wealthiest and fastest-growing suburbs in the nation.