Brigadier General Count Casimir (or Kazimierz) Pulaski came from Poland to fight in the American Revolution (1775-83). Frequently hailed as the founder of the American cavalry, he served in the Continental Army from late 1777 and died during the Siege of Savannah in October 1779.

Casimir Pulaski was born in Warsaw, Poland, on March 6, 1745, to Marjanna and Jozef Pulaski, members of an old and influential branch of the Polish aristocracy. Baptized as a boy, the young Pulaski received a general education geared for male children of the nobility. His family became heavily involved in the 1768 conspiracy, known as the Confederation of Bar, to free Poland from Russia’s political influence. Pulaski, who always presented as masculine, joined the effort and quickly exhibited an ability to command a powerful mobile force against Russian troops. In 1771 the Polish government implicated Pulaski in a plot to abduct Stanislaus II, the Russian-controlled king, and accused him of treason. Pulaski sought protection in France and in 1773 briefly commanded an international force during the Russo-Turkish War (1768-1774).

Courtesy of Georgia Historical Society.

By 1777 the Revolutionary War in America had caught Pulaski’s attention. He not only sympathized with the new nation’s struggle against oppression but also saw the conflict as a possible means to regain his military reputation in Europe and remake his fortune. He obtained the help of Benjamin Franklin, one of the American ambassadors in France, and sailed for America in June 1777. Pulaski quickly submitted his name to the Continental Congress for an officer’s commission. To demonstrate his zeal for the war’s success, he supplemented the application with a variety of military proposals, including an expedition to capture the French-held island of Madagascar.

Pulaski’s past military commands and his reputation as a skilled cavalry officer did not cause George Washington or the Continental Congress to accept him immediately. They had grown weary of Europeans who applied for military service and did not live up to their vaunted reputations. So Pulaski unofficially joined Washington’s forces on September 11, 1777, at the Battle of Brandywine in Pennsylvania, where he led a small force of horsemen and helped protect the Continental Army during its retreat. His fervor for the American cause and ability in battle convinced Washington and Congress to accept Pulaski as a brigadier general and appoint him “Commander of the Horse.” He fought at the Battle of Germantown, also in Pennsylvania, later that year and briefly stayed at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, during the winter of 1777-78. Most contemporaries who met Pulaski agreed that he excelled as a daring and energetic horseman; one friend described him as a soldier who fought with the force of ten men.

Yet he faced the difficult task of combining four semi-independent commands of Continental dragoons. Speaking little English, Pulaski discovered to his dismay that Washington and most of his generals failed to grasp the potential effectiveness of a highly trained, cohesive cavalry unit; indeed, sections of his corps were detailed as messengers and guards. Pulaski insisted that his men follow European-style cavalry tactics, act as shock troops in battle, and learn to harass the enemy on the march.

Photograph by Brooke Novak

To make matters worse, Congress rarely appropriated adequate funds for the cavalry, and prices for provisions rose steadily. Pulaski’s desire to supply and train his command properly led him to act impetuously at times and ignore the mundane tasks of administration. Few contemporaries questioned his commitment to the American cause, but his actions angered Congress, civilians, and military personnel. His letters to friends and acquaintances frequently conveyed a strain of melancholic disillusion about life in the American army.

During the spring of 1778, Pulaski briefly resigned his commission with the intent of returning to France. But that year Congress approved his command of an independent legion and gave him permission to train it in the European fashion. Pulaski’s legion quickly gained an international character, with American, Hungarian, German, Polish, Swedish, Italian, and French volunteers. Pulaski hoped to demonstrate the capabilities of his command, but setbacks continued to hinder his efforts. For example, an infantry unit from the legion suffered a surprise night attack by the British at Little Egg Harbor, New Jersey, in October 1778. Washington then assigned the legion to border patrol at Cole’s Fort in New York, located on the northern frontier. It proved a place unfit for cavalry tactics, and once again Pulaski determined to leave America.

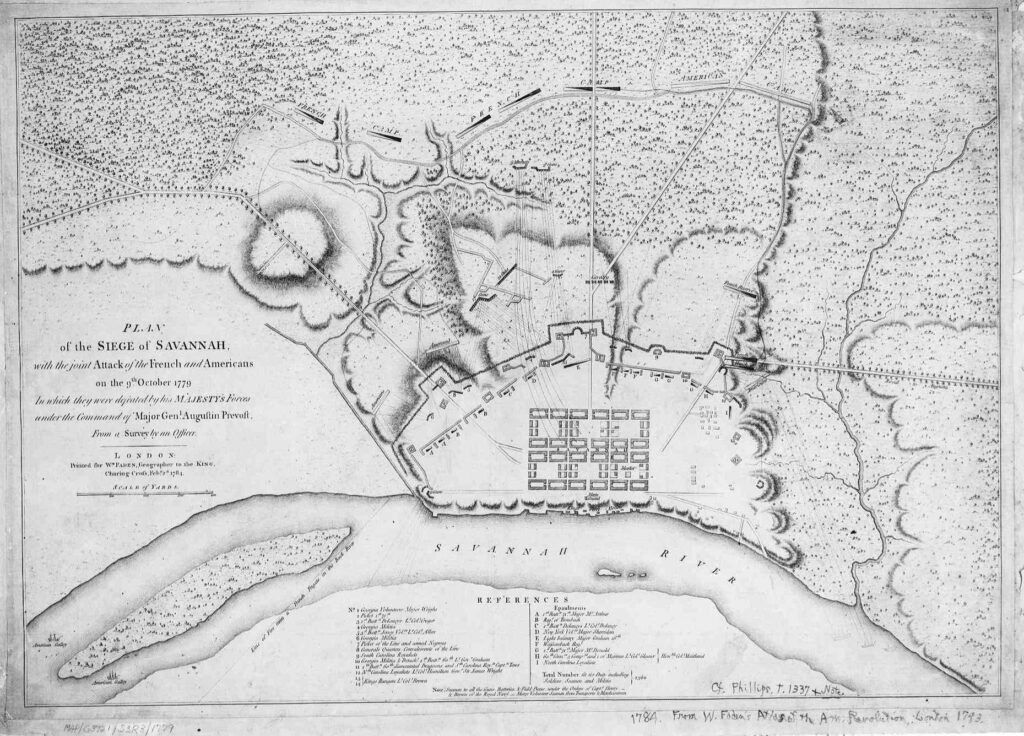

But events in Georgia kept Pulaski in the army and brought him to the South. Earlier, in December 1778, British forces took Savannah by surprise. In response Washington ordered Pulaski’s legion and several Continental units to join the forces of General Benjamin Lincoln, commander of the Southern Army. Once in South Carolina, the legion helped defend Charleston from a surprise British attack and fought at the Battle of Stono Ferry. By mid-September 1779 the legion marched with Lincoln to join French troops under Count Charles Henri d’Estaing in a campaign to retake Savannah.

In October the French-American force began a devastating bombardment of the town that lasted five days. But d’Estaing’s fears for the supporting French fleet of remaining too long in Georgia during the hurricane season forced the Allies to make a frontal attack against the British defenses on the ninth. The approved plan called for a diversionary assault on the British left followed by the main attack of French and American troops upon the British right at the Spring Hill redoubt. The American infantry served as a follow-up force, while Pulaski’s men were to launch a cavalry charge whenever a breach occurred in the defenses to create havoc among the enemy troops.

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

The attack failed to unfold as planned. Allied troops started late, as fog and a lack of clear directions delayed the French columns. Once the assault began, the Allies quickly realized that the British knew of their plans. Eyewitness accounts of Pulaski’s charge vary. Captain Paul Bentalou, a member of the legion, wrote that the general rode into battle when he heard news that d’Estaing was wounded. Another legionnaire, Maciej Rogowski, claimed that Pulaski and his men found themselves caught in a crossfire between two batteries. D’Estaing recalled that Pulaski charged too quickly and cut himself off from support. All accounts conveyed the grim news that grapeshot from a British cannon cut into the general when he attempted to crash though the enemy lines.

Pulaski died within two days of his wounding. Rumors and controversies about the exact cause of death and place of burial emerged within a few decades of Pulaski’s demise and continue to exist. James Lynah, the physician who removed the fatal grapeshot, claimed that he could have saved Pulaski if the general had remained in the American camp, but he insisted upon boarding a ship. The standard account of Pulaski’s death comes from Captain Paul Bentalou in an 1824 essay entitled “Pulaski Vindicated from an Unsupported Charge….” in which he claims that his commander died of gangrene aboard the Continental brigantine Wasp. Rapid deterioration of the body forced a burial at sea near Tybee Island, of which Bentalou claimed to be an eyewitness. A different account has Pulaski buried in South Carolina, while another report tells of a secret burial at Greenwich Plantation near Thunderbolt, in Chatham County, Georgia.

When the city of Savannah erected a fifty-five-foot obelisk in Monterey Square to honor Pulaski during the 1850s, examiners exhumed the Greenwich Plantation grave believed to contain his remains. They pronounced the bones similar to a male the same age and height of the general. City officials reburied the remains underneath the monument in 1854. A more recent interpretation by Edward Pinkowski supports the Greenwich burial location and relies upon a letter written by the captain of the Wasp, Samuel Bullfinch, dated October 15, 1779. Captain Bullfinch notes that his ship lay off Thunderbolt and reported the burial detail of an American officer who had recently died aboard the ship and was given a funeral on land.

Courtesy of the Smithsonian National Postal Museum

When plans were made to disassemble and renovate the Monterey Square monument in the fall of 1996, the Pulaski DNA Investigation Committee exhumed the grave and had DNA taken from the remains compared with that from members of the Pulaski family buried in eastern Europe. Supporters of the theory that Pulaski’s body lay in Monterey Square stressed that the skeletal remains revealed broken bones in the right hand as well as injuries to the head and tailbone similar to wounds suffered by the general. Yet, the unearthed remains had characteristically female pelvic bones and a delicate facial structure. At the time DNA testing did not prove conclusive, but some bone samples were retained in hopes that DNA technology improved in the future. On October 9, 2005, the 226th anniversary of the Siege of Savannah, the city organized special funeral services and a final reinterment ceremony at Monterey Square to honor the fallen soldier.

In 2015, Virginia Hutton Estabrook, an anthropology professor at Georgia Southern University and Lisa Powell, then a graduate student, began to reexamine the data. With support from the Smithsonian Channel, the team ran additional DNA tests and, this time, the results proved conclusive: the mitochondrial DNA matched a known Pulaski relative. Given the skeletal remains’ characteristically female pelvic bones and facial structure, the team concluded that Pulaski was intersex. According to the Intersex Society of North America, “intersex is a general term used for a variety of conditions in which a person is born with a reproductive or sexual anatomy that doesn’t seem to fit the typical definitions of female or male.” Pulaski presented as male throughout his life, and he may have been unaware of his condition. In 2019, this recent discovery, as well as Pulaski’s distinguished military career, was featured in a Smithsonian Channel documentary. Pulaski is now publicly recognized as an important historical figure from an often obscured and marginalized community.

Fort Pulaski, built at the mouth of the Savannah River to protect Savannah from Union attack during the Civil War (1861-65), and Pulaski County were named for the Revolutionary War officer.