Charles Rinaldo Floyd, the third child and second son of General John Floyd, followed his father into battle, plantation society, and the political arena in the early nineteenth century.

During the Second Seminole War (1835-42), Floyd was most famous for his excursion into the Okefenokee Swamp in the winter of 1838-39, although this campaign has often been mistakenly credited to his father. Throughout his life Charles Floyd kept a vivid and engaging diary that portrays an active life of privilege and violence in the Georgia Lowcountry.

Early Life

Charles Rinaldo Floyd was born on October 14, 1797, at “The Thickets” in Darien to Isabella Maria Hazzard and John Floyd. When he was three years old the family (including Floyd’s grandfather, for whom he was named) moved to Camden County and built two plantations—Fairfield and Bellevue—near the Satilla River. Floyd was educated at home by tutors until he was old enough to attend a small school in Beaufort, South Carolina, and then the Sunbury Academy in Sunbury, Georgia. At age sixteen he left the academy and joined his father’s regiment at Fort Mitchell. At the time John Floyd, operating jointly with Andrew Jackson, was leading an expeditionary force of Georgia militia against Creek warriors along the southwestern Georgia frontier. The young Floyd served as his father’s military aide during the major battle at Autossee and other skirmishes.

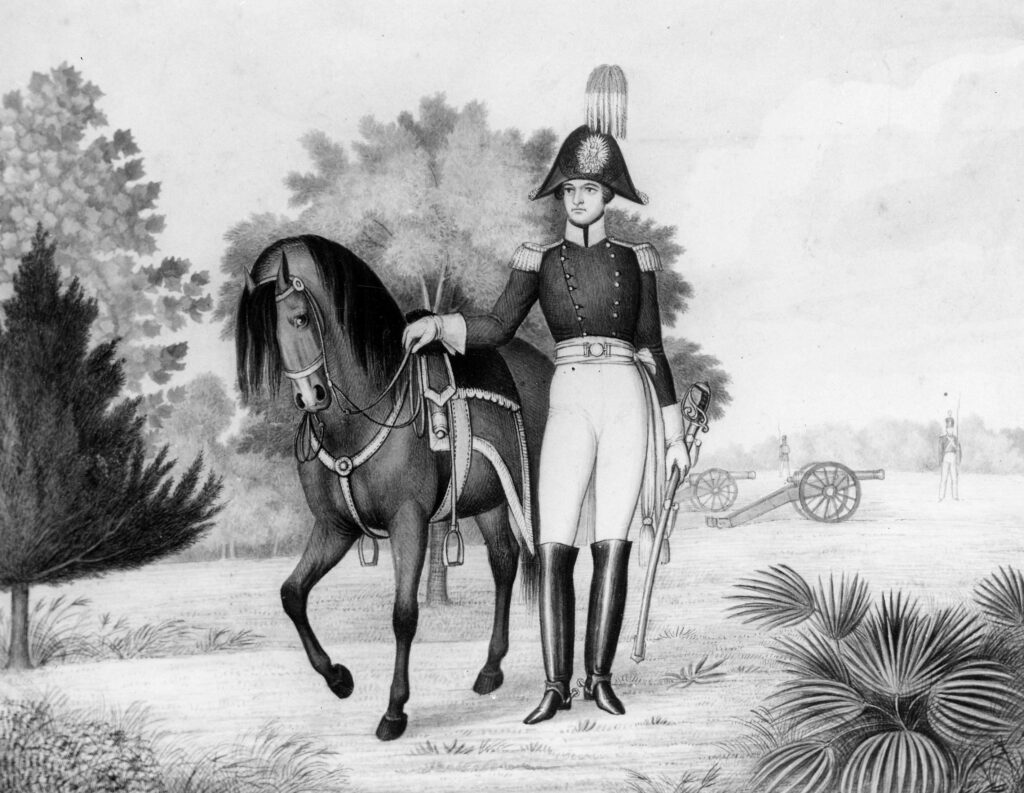

When the battles ended (in Georgia’s favor, but with great loss of life), Floyd attended the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York. He was dismissed in 1817 for insubordination over what he considered “a point of honor.” Floyd’s high regard for honor and his early training as a soldier resulted in a penchant for dueling, a practice he engaged in throughout his lifetime. After his dismissal from West Point, Floyd received a commission as lieutenant in the marines. During an extended leave, he traveled to England and the Napoleonic battlefields of Europe. When he returned in 1823 he married Catherine Sophia Powell and moved to Boston. They had two daughters, the younger of the two named Autossee after the Floyd family’s most famous moment to date. Floyd experienced another famous moment when, as commander of a marine honor guard, he was sent to meet the Marquis de Lafayette upon his arrival in New York City in 1824.

Return to Georgia

In 1828 Floyd lost both his younger daughter and his wife to illness. He moved back to the family plantations and was soon circulating in Georgia plantation society. He met Julia Ross Boog at one such society outing, and they married in 1831. They had seven children (three girls and four boys) together, and Floyd settled into plantation life at Bellevue and Fairfield, overseeing the cultivation of orange and olive trees and more than 200 enslaved people. Floyd continued to see any affront to his honor as a mortal threat and engaged in many high-profile (and some said arbitrary) duels in the late 1830s—in October 1837, Charles shot his neighbor, Edward S. Hopkins, in the left thigh and right calf over a cattle dispute. One year later, while he was serving as brigadier general of the Georgia militia, Floyd received a military assignment that would make him almost as famous as his father in southern Georgia.

Okefenokee Campaign, 1838-1839

The U.S. Army had been embroiled in the Seminole Wars in Georgia and Florida during the 1810s and again in the 1830s. While much of the action in the Second Seminole War took place in north central Florida, groups of Seminoles often confused American troops by taking refuge in the Okefenokee Swamp. In October 1838 Floyd was ordered to meet five companies of troops (300 soldiers) on the southwestern side of the swamp in order to chase the Seminoles out of their stronghold. He immediately set out to meet his troops and made his first foray into the Okefenokee in early November. During the campaign he faced an early mutiny, illicit alcohol use among the men, scattered Seminole bands that struck and ran, and the disorienting ecology of the swamp itself. He and his troops did manage to traverse the Okefenokee a number of times in their search for “the enemy,” marching “through the most infernal places” and emerging from its fastnesses “worn down with fatigue, and many were without shoes, hats, & pantaloons, these articles having been destroyed by the obstacles in the swamp.”

Though local lore has it that Floyd and his men engaged with more than 100 Seminoles, killing many and evicting the rest from their Okefenokee town, in reality Floyd’s soldiers found only one abandoned village (which they burned) on an island. The soldiers named it Floyds Island after their commander, an act that Floyd proudly reported in his diary. Single battalions engaged once or twice with small Seminole bands, but most of Floyd’s time was spent exploring the Okefenokee. For three months he investigated and then wrote about the swamp (which before that point had been something of a terra incognita to Anglo-Americans) for his superiors and for local newspapers. Floyd’s most important contribution to the Second Seminole War was the incursion into the Okefenokee itself and the publication of his findings.

Return to Fairfield

Floyd left the Okefenokee in March 1839 after three months of exploration, riding back to his Fairfield plantation full of stories to relate to his father and his children. John Floyd was not able to savor his son’s achievements for long, however; he died three months later, on June 24, 1839, and appointed Floyd an executor of his will. Charles Floyd continued to manage the lands of both Bellevue and Fairfield, planting a variety of crops and orchards. In April 1843 he sold 2,000 acres of marshland for $400 and used the money to run his plantations and to fund his hobbies: building champion race boats, founding and running the Camden County Hunting Club, and collecting rare weapons. Floyd stayed at Fairfield most of the time, and it was there that he he died on March 22, 1845.

Floyd’s family followed his wishes that he be buried, wrapped in an American flag, under a large “sentinel” pine tree in his backyard at Fairfield. After the funeral, one of his descendants reported, “a new pathway was made in the garden, leading to the pine. It had a wide border of violets and white hyacinths.” His obituary in the Savannah Daily Republican (March 28, 1845) lauded his “many social and manly virtues . . . his exalted genius and varied attainments.” His lasting legacy, however, was not the duels or the gun collection or the groves of Fairfield, but his written account of his life and of the Okefenokee. These documents have given historians a better sense of the life of a typical southern gentleman-planter, the exigencies of battle during the antebellum era, and the nature of Georgia’s “great natural wonder”—the Okefenokee Swamp.