The three Seminole Wars that commanded the attention and manpower of the U.S. Army and Navy during the antebellum period intensified the violence and chaos that had been characteristic of the Georgia-Florida frontier since the early colonial period.

The engagements that took place between American troops and the Seminoles in Georgia, particularly during the First (1817-18) and Second (1835-42) Seminole Wars, were pivotal moments that crystallized some of the major issues underlying the battles.

British, Spanish, and French colonists had been, at best, uneasy allies with Native American nations in the Southeast since initial contact in the sixteenth century. Conflicts over trade agreements and land cessions resulted in small-scale skirmishes that ultimately exploded into declared warfare.

Emergence of the Seminoles in Southern Georgia

The antebellum period Seminoles were a confederacy of multiple clans that had splintered from various southwestern tribes (Lower Creek, Oconee, Yuchi, Alabama, Choctaw, and Shawnee) and drifted into southern Georgia and northern Florida in the early 1700s. These disparate bands, without much in common but geography, began to hunt, fish, farm, and herd livestock in the area. By 1750 clans had built towns along the Suwannee River, linked to other Native American and maroon (fugitives from slavery) villages through infrastructure (roads, shared outbuildings) and intermarriage. After 1767 Upper Creeks began to move into the area, increasing the Native borderland population to more than 2,000 by 1790. It was at this point that Spanish and British American colonists commenced identifying all of these clans as “Seminoles.” (There is some dispute about the origin of the term Seminole. Some scholars have argued that the term originates from cimarrones, a Spanish word meaning “rebel” or “outlaw.” Cimarrones was used among the Spanish to identify both fugitives from slavery—”maroon” emerges linguistically from this root as well—and Native Americans along the border. There is also evidence that antebellum Americans understood Seminole to refer to “wild people,” “pioneers,” “adventurers,” and “wanderers” in Georgia and Florida.) An 1890 census estimated that there were about 5,000 Seminoles living along the Georgia-Florida border at the start of the First Seminole War.

First Seminole War

In November 1817 a detachment of soldiers stationed at Fort Scott in southern Georgia traveled to the Seminole village of Fowl Town, fifteen miles away and just north of the Florida (Spanish) border. The soldiers demanded that the Seminole chief Neamathla surrender warriors whom American military officials believed responsible for the murder of several Georgia families. Neamathla refused. In response the soldiers drove the Seminoles into the surrounding swamplands (killing about twenty men) and then plundered and burned Fowl Town. Both Seminoles and Georgians living along the frontier immediately arose, and the First Seminole War began.

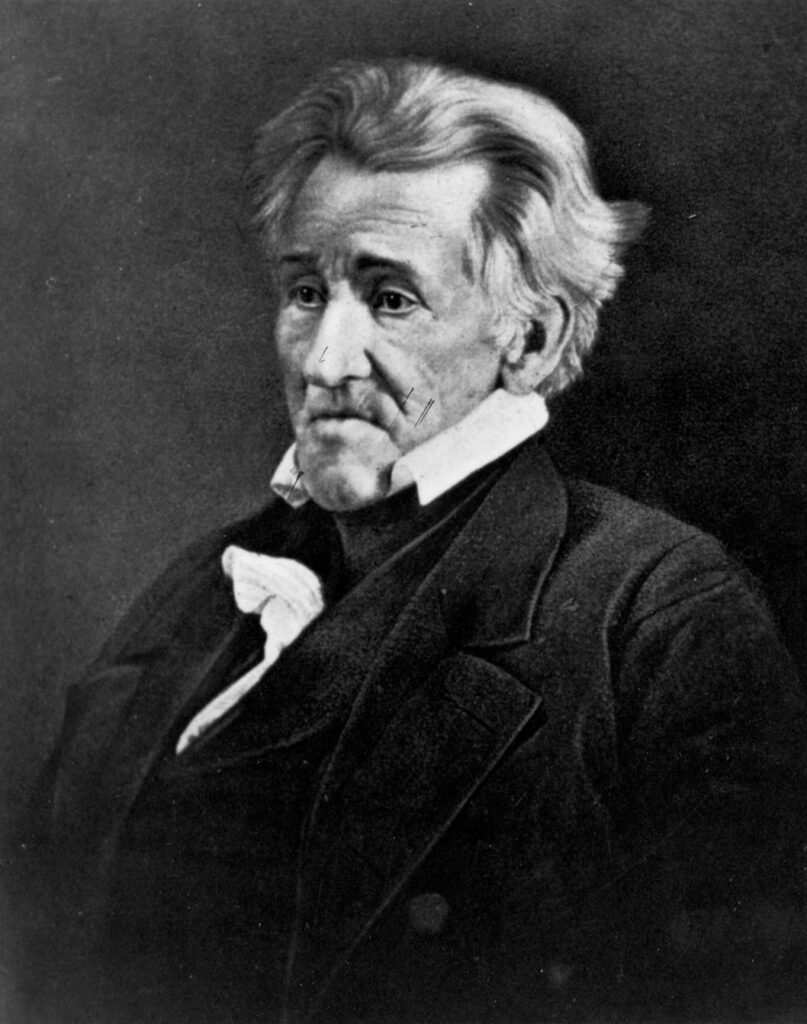

These battles, which lasted for a little less than a year, were characterized by hit-and-run attacks by the Seminoles on frontier plantations and towns and American retaliations. After General Andrew Jackson took control of American troops in January 1818, his efforts weakened Seminole offenses by dividing their numbers between Georgia and Florida. In April of that year, Jackson and his troops marched against the Seminole villages along the Suwannee River, ultimately chasing the Seminoles into the Okefenokee Swamp. Jackson then left Georgia and marched—mostly unopposed—through East Florida, destroying Seminole towns, Spanish forts, and British plantations. The First Seminole War was the result of conflicts over land and trade between Seminoles and Georgia colonists. The most important outcome of the war was the acquisition of Florida from Spain in 1819.

Second Seminole War

The years between the cessation of the First Seminole War and the commencement of the Second Seminole War were not peaceful along the Georgia-Florida frontier. American attempts to relocate Seminole men and women were met with resistance, and warriors began buying ammunition in large quantities in October 1834. In December 1835 small-scale skirmishes again exploded into war when a group of Seminoles and maroons initiated a two-pronged attack against U.S. troops in north central Florida, killing more than 100 soldiers.

Throughout the course of the war, Seminoles confused their enemies by backtracking from Florida battle sites up into southern Georgia. They traveled back and forth across the border and established refuge sites in the Okefenokee Swamp, prompting Ware County militia commander Thomas Hilliard to complain to his superiors in August 1836 that the Seminoles “go concealed as much as possible, and are committing depredations continually, robbing our corn fields and killing our stock.” By November 1838 the situation demanded American military action, and Georgia governor George R. Gilmer announced that he had raised a regiment to operate under the command of General Charles Rinaldo Floyd. Floyd’s regiment, he asserted, would destroy or drive from the state “the savage enemy.”

Okefenokee Campaign, Winter of 1838-1839

Floyd was the son of Congressman John Floyd, a military general, and he had accompanied his father during several engagements in the course of his military training. His Okefenokee incursion of 1838-39 ultimately was deemed a success, not because he had defeated the Seminoles within its borders but because, by virtue of entering the swamp, Floyd claimed its expanse for the state of Georgia.

When Floyd arrived at the southwestern edge of the Okefenokee in early November 1838, he found five companies waiting for him, a total of 300 noncommissioned officers and privates. One week later the troops entered the swamp, and over the next several days Floyd’s companies found an island that had previously housed 150 Seminoles. The soldiers called it Floyds Island. During the Okefenokee Campaign, which lasted three months, Floyd and his men encountered very few Seminoles and managed to cross the Okefenokee several times and record their impressions. In his own estimation Floyd’s adventures in the swamp would be “of great utility—they will enable us hereafter to exclude the Indians from the Okefenokee, [and] open to the citizens of Georgia new sources of wealth in the rich lands of the swamp.”

After Floyd’s Okefenokee Campaign, the action of the Second Seminole War moved southward into peninsular Florida. But the swamp area remained unstable until a frustrated U.S. president John Tyler declared a cease-fire on May 10, 1842. Eight years later a survey team, funded by the state of Georgia and led by surveyor Mansfield Torrance, entered the Okefenokee and completed Floyd’s mission by mapping and marking the morass.

The Georgia battles during the Second Seminole War revealed that the southern parts of the state were critical spaces in the antebellum period. They were places in which the battles over land and trade were waged, and where ideas about “civilization” and “nationhood” were contested.