The Crypt of Civilization, a multimillennial time capsule, is a chamber that was sealed behind a stainless steel door in 1940 at Oglethorpe University in Atlanta. The crypt is the “first successful attempt to bury a record of this culture for any future inhabitants or visitors to the planet Earth,” according to the Guinness Book of World Records (1990).

Origins of the Crypt

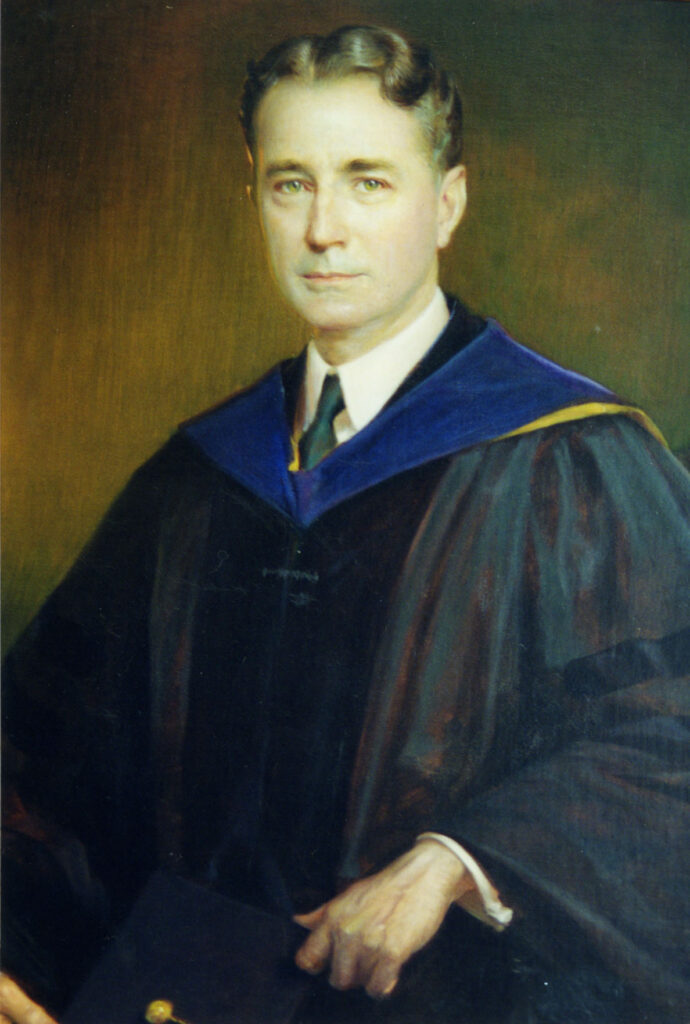

Oglethorpe University president Thornwell Jacobs (1877-1956), in an article in the November 1936 Scientific American magazine, claimed to be the first to conceive the idea of consciously preserving artifacts for posterity by placing them in a sealed repository. While engaged in research and inspired by the openings of the Egyptian pyramids in the 1920s, Jacobs was struck by the relative lack of information on ancient civilizations. He later wrote of a unique plan to preserve a “running story” of life and customs, to show the ways of life in 1936 as well as the accumulated knowledge of humankind up until that time.

Courtesy of Oglethorpe University Archives

Jacobs proposed the distant date of A.D. 8113 for the opening of the crypt. He calculated this date from the first fixed date in history, 4241 B.C., when the Egyptian calendar was established. Exactly 6,177 years had passed between 4241 B.C. and A.D. 1936. Jacobs projected the same period of time forward, arriving at 8113 for the crypt’s opening, so that historians and archaeologists of the distant future could obtain a clear picture of the midpoint of history.

The Crypt of Civilization idea fascinated the American public and soon was imitated. The Westinghouse Company, which was planning a promotional event for the 1939 New York World’s Fair, began a project to bury a sealed seven-foot-long torpedo-shaped vessel made of alloyed metal, which was not to be opened for 5,000 years. George Pendray of Westinghouse called the project a time capsule, and the English language gained a new term almost overnight.

Construction and Preparation of the Crypt

The Oglethorpe crypt is half underground, on the lower level of a Gothic granite building, Phoebe Hearst Hall, in a room that had held a swimming pool with a waterproof foundation. Remodeling of the chamber took place from 1937 to 1940. Construction included raising the floor with concrete and lining the walls with enamel plates embedded in pitch. The crypt is twenty feet long, ten feet wide, and ten feet high. It lies over a two-foot stone floor and under a stone roof seven feet thick.

Image from Oglethorpe University

The National Bureau of Standards in Washington, D.C., provided technical advice for construction of the crypt and the storage of items in it. The bureau recommended that many items be stored in stainless steel receptacles lined with glass and filled with nitrogen to prevent aging. It also approved Jacobs’s plan to seal the chamber with a door panel of stainless steel.

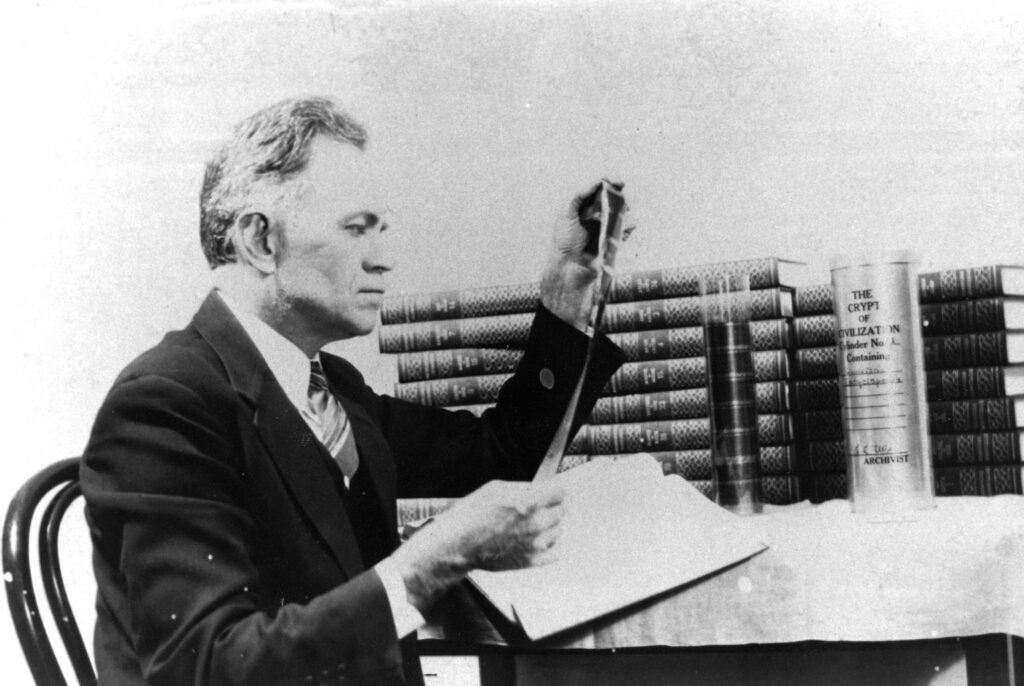

Jacobs appointed Thomas Kimmwood Peters to supervise construction of the crypt and to serve as its archivist. Peters, an inventor and photographer, invented the first microfilm camera using 35 mm film to photograph documents. From 1937 to 1940 Peters and a staff of student assistants conducted an ambitious microfilming project to place cellulose acetate film in airtight receptacles. As backup in case the acetate did not survive, Peters prepared duplicate metal film, thin as paper, to place in the crypt. Peters secured for time storage numerous items, all of which were donated. The hundreds of contributors were as diverse as King Gustav V of Sweden and the Eastman Kodak Company.

Courtesy of Oglethorpe University Archives

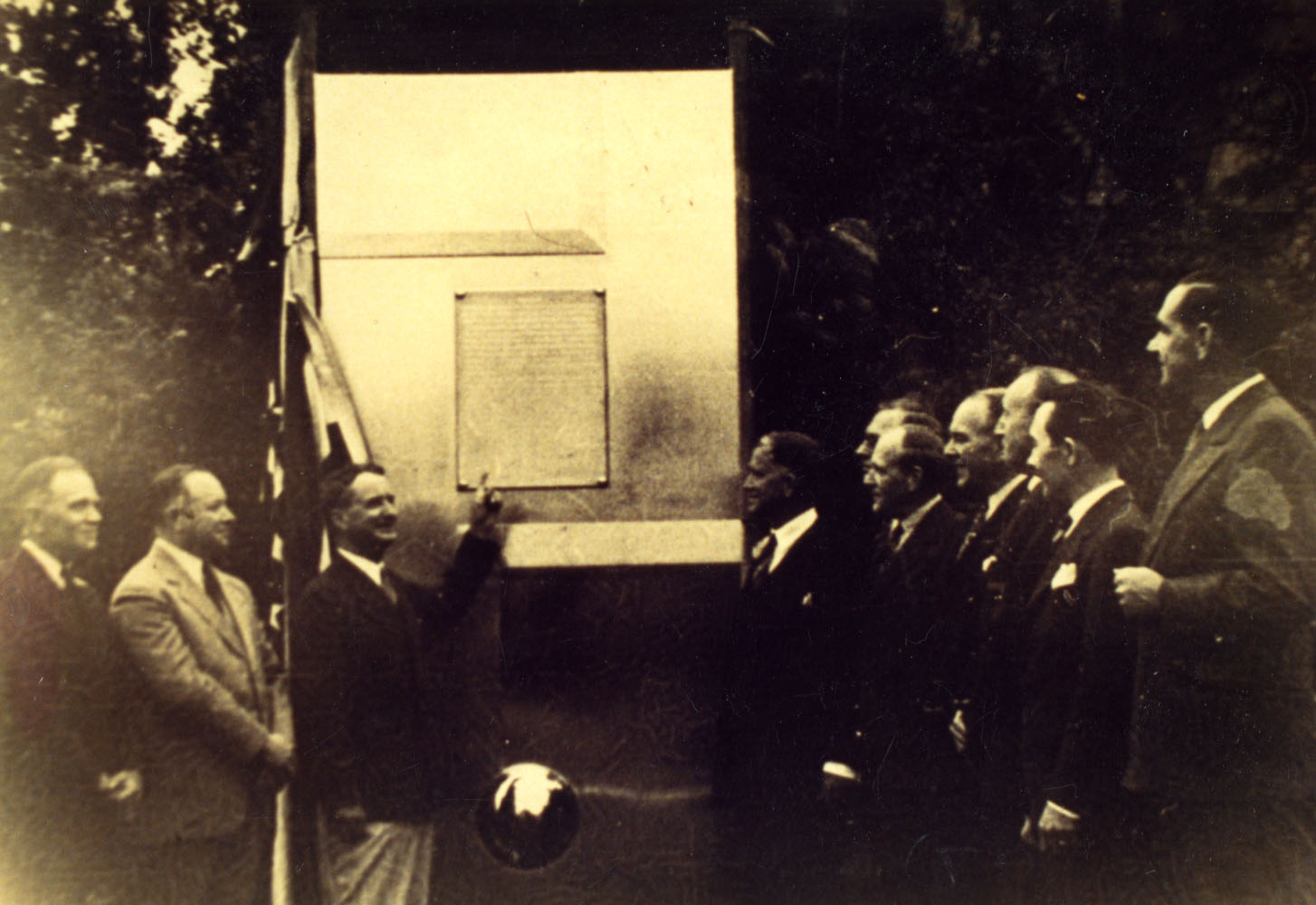

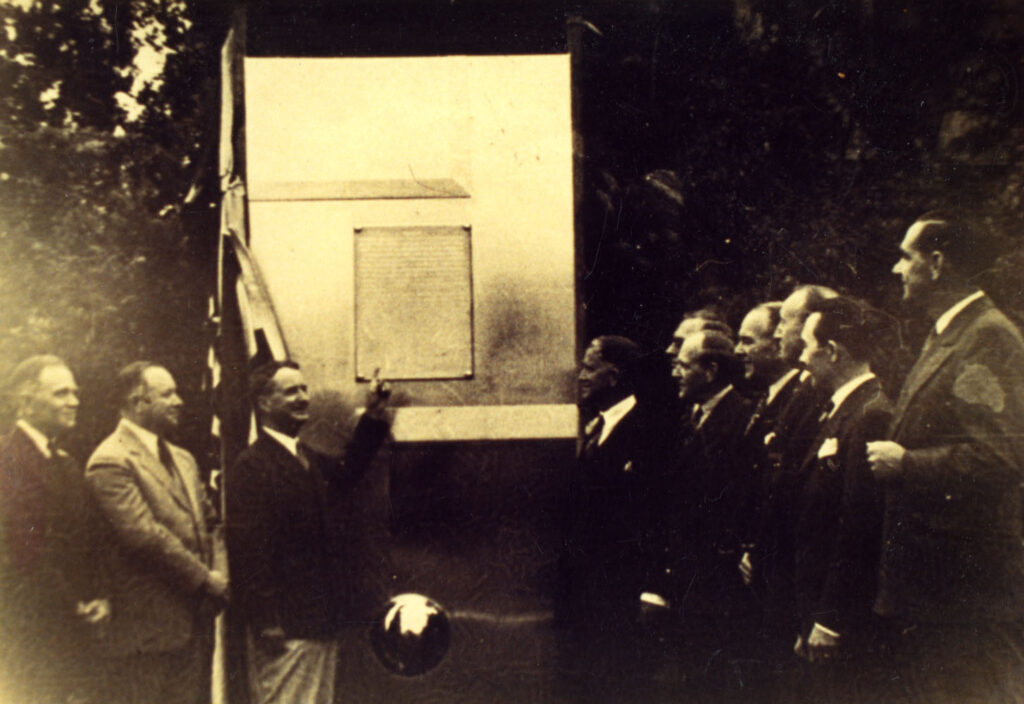

In April 1937 Jacobs gave a nationwide radiocast on NBC in New York City, in which he explained the crypt as an “archaeological duty” of his generation. He also recorded his “Message to the Generations of 8113 A.D.” In May 1938, in an outdoor ceremony on the Oglethorpe University campus, David Sarnoff of the Radio Corporation of America dedicated the crypt’s stainless steel door, which was to be sealed two years later. Paramount newsreels filmed the occasion. Peters included these segments in The Stream of Knowledge (1938), a film about the crypt.

Courtesy of Oglethorpe University Archives

Filling and Sealing the Crypt

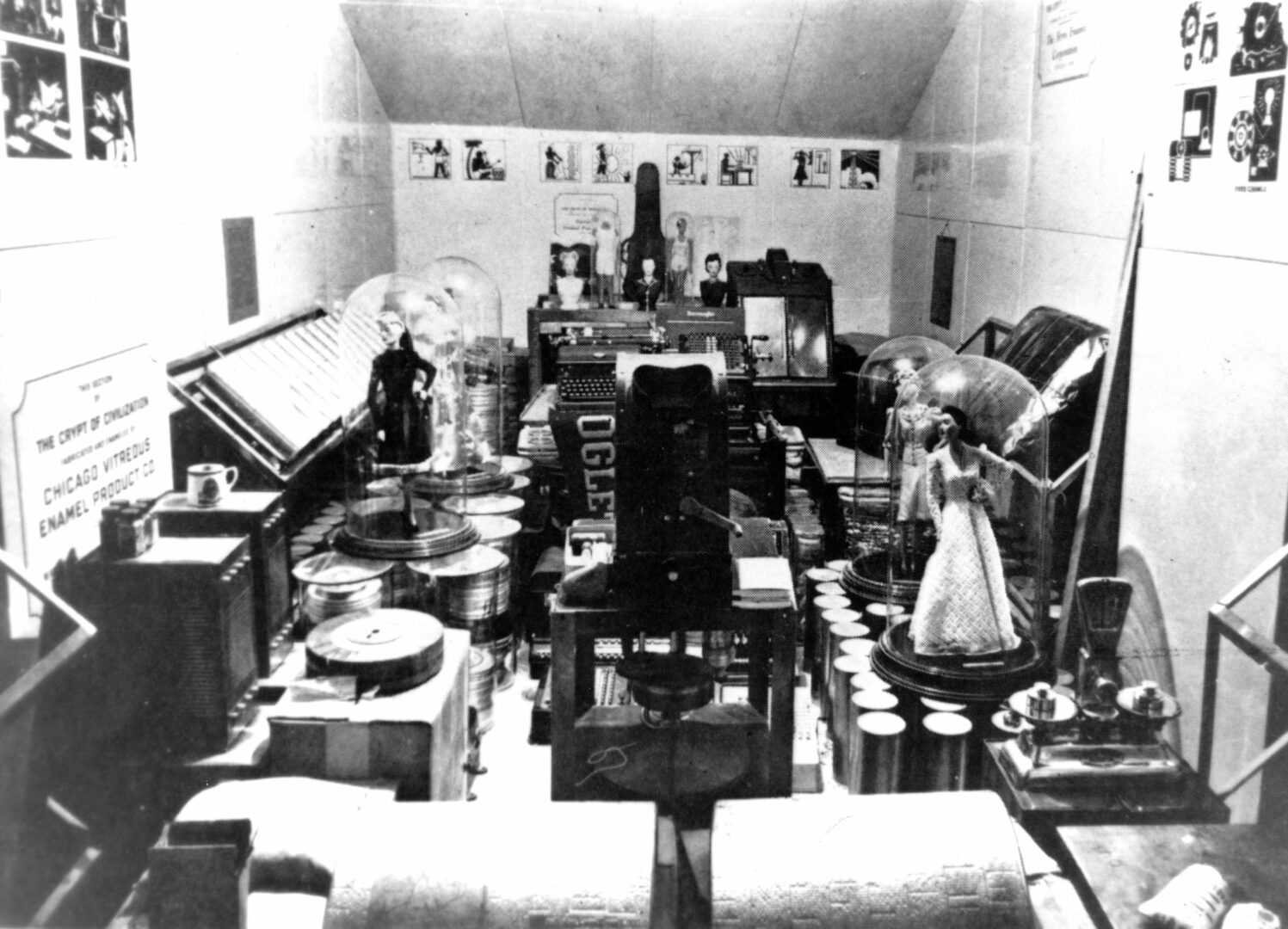

Jacobs envisioned the crypt as comprehensive and aimed for a whole “museum” not only of accumulated formal knowledge from more than 6,000 years but also of 1930s popular culture. Inside the crypt are stainless steel canisters with microfilms of many classic works of literature, including the Bible, the Koran, Homer’s Iliad, and Dante’s Inferno. Producer David O. Selznik donated an original copy of the script for the movie Gone With the Wind. There are approximately 640,000 pages of microfilm from more than 800 works.

Peters used similar methods to capture and store still photographs and motion pictures. Voice recordings of Adolf Hitler, Joseph Stalin, Benito Mussolini, and Franklin Roosevelt are among items placed in the crypt, as well as sound clips of the cartoon character Popeye the Sailor and a champion hog caller. To be sure the openers of the crypt could see and hear these records, Peters placed electric microreaders and projectors in the vault. In the event that electricity is not in use in 8113, the crypt holds a generator operated by a windmill to drive the apparatus, as well as a seven-power magnifier to read the microfilm records by hand. In the front of the sealed chamber is the “language integrator,” a machine to teach those who open the crypt how to speak English.

Courtesy of Oglethorpe University Archives

The inventory of the crypt includes artifacts ranging from the useful (a typewriter, a radio, a cash register, and an adding machine) to the curious (dental floss, plastic toys of Donald Duck and the Lone Ranger, the contents of a woman’s purse, and a specially sealed bottle of Budweiser beer). The chamber of the crypt when finished resembled a cell of an Egyptian pyramid, with artifacts on the shelves and the floor.

On May 25, 1940, Jacobs and Peters sealed the crypt in a solemn ceremony. They welded the door shut and fused onto it a plaque with an elaborate message written by Jacobs. Representing the federal government on the occasion was Postmaster General James A. Farley. The last items placed in the vault were steel press plates of the Atlanta Journal, in which reports of World War II (1941-45) predominated, as well as a voice recording by Jacobs. Addressing the people of 8113, he said, “The world is engaged in burying our civilization forever, and here in this crypt we leave it to you.”

Courtesy of Oglethorpe University Archives

After the atomic bomb was dropped in 1945 the crypt’s mission appeared even more unlikely. National media organizations continued to visit the crypt every decade, butby 1970 it had been virtually forgotten. In 1990, on the fiftieth anniversary of the crypt’s sealing, the International Time Capsule Society was formed at Oglethorpe University. The society studies the variety of time capsule projects worldwide. The crypt with its stainless steel door regained prominence during the millennium observances from 1999 to 2001 and was featured on national television and was covered by national newspapers.