Among southern states, only Mississippi, by virtue of William Faulkner, Eudora Welty, Tennessee Williams, and Richard Wright, has produced a richer literature than Georgia. With such authors as Conrad Aiken, Erskine Caldwell, James Dickey, Joel Chandler Harris, Carson McCullers, Flannery O’Connor, and Alice Walker (not to mention Margaret Mitchell), Georgia holds a position of considerable literary prominence.

Georgia writing developed in response to the same events and forces that shaped the national literature: the disappearance of the frontier, the expansion of industry, the growth of cities, the trauma of war and depression, and the tumultuous events of the twentieth century. Yet factors unique to the state also left their marks. The relatively late founding of the Georgia colony in 1733 and the persistence of the frontier well into the nineteenth century significantly influenced the state’s literature—especially its penchant for humor and violence—and its emphasis on regional themes and settings. In the twentieth century, the explosive growth of Atlanta and its impact on surrounding areas has also played a powerful role.

Beginnings to 1900

The first writing in Georgia was not really intended to be literature. It came in the form of letters, diaries, journals, political speeches, and newspaper articles. These provide a valuable record of the state’s early history and of the lives of its residents. General James Oglethorpe’s journal entries, for instance, report on the early days of the colony’s settlement, while Hugh McCall’s History of Georgia (1811-16) chronicles the colony’s development through the end of the eighteenth century.

But the first important literature did not appear until early in the nineteenth century, when the prominence of the frontier in Georgia, and the southeastern United States in general, gave rise to the nation’s first native literature. Sometimes called frontier humor or humor of the old Southwest, old southern humor was a rowdy, vital form of writing that vividly described life on the frontier. The men who wrote it usually did not consider themselves “literary” authors. The Georgia humorists were lawyers or doctors or itinerant salesmen who wrote as a hobby or to pass the time while traveling from one town to another. Their humor usually took the form of unpolished short sketches and anecdotes narrated by a relatively educated man describing with condescension and relish the activities of people along the frontier.

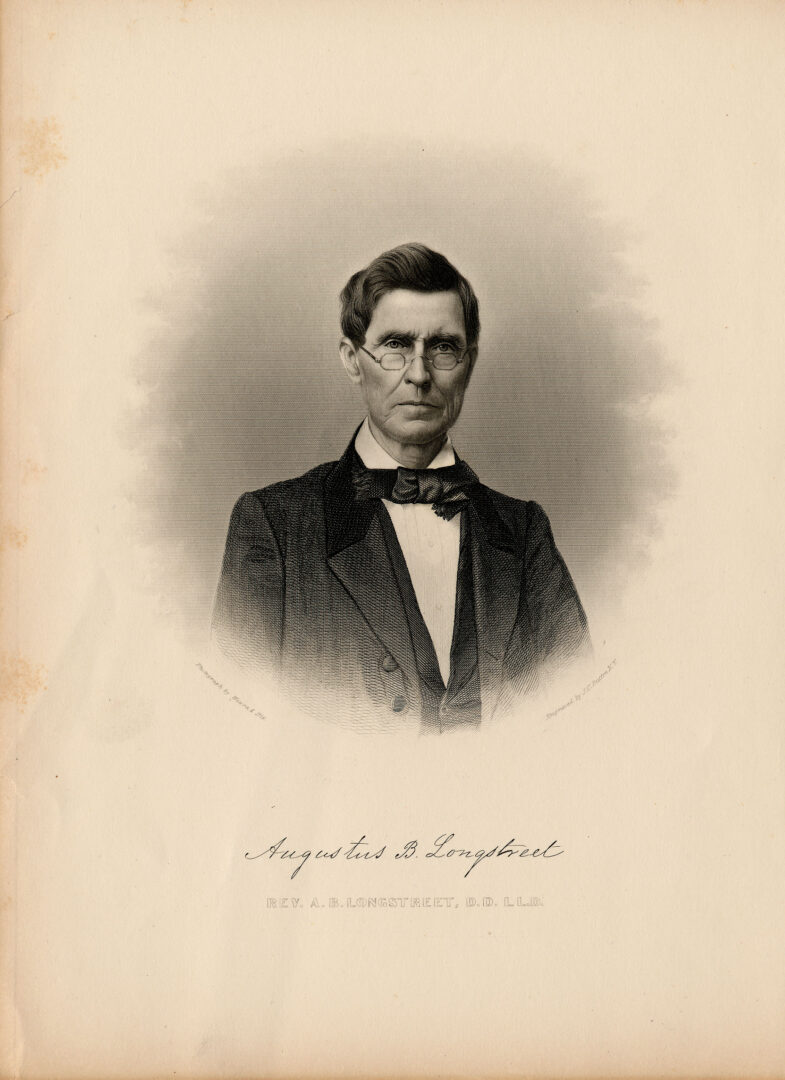

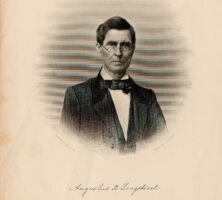

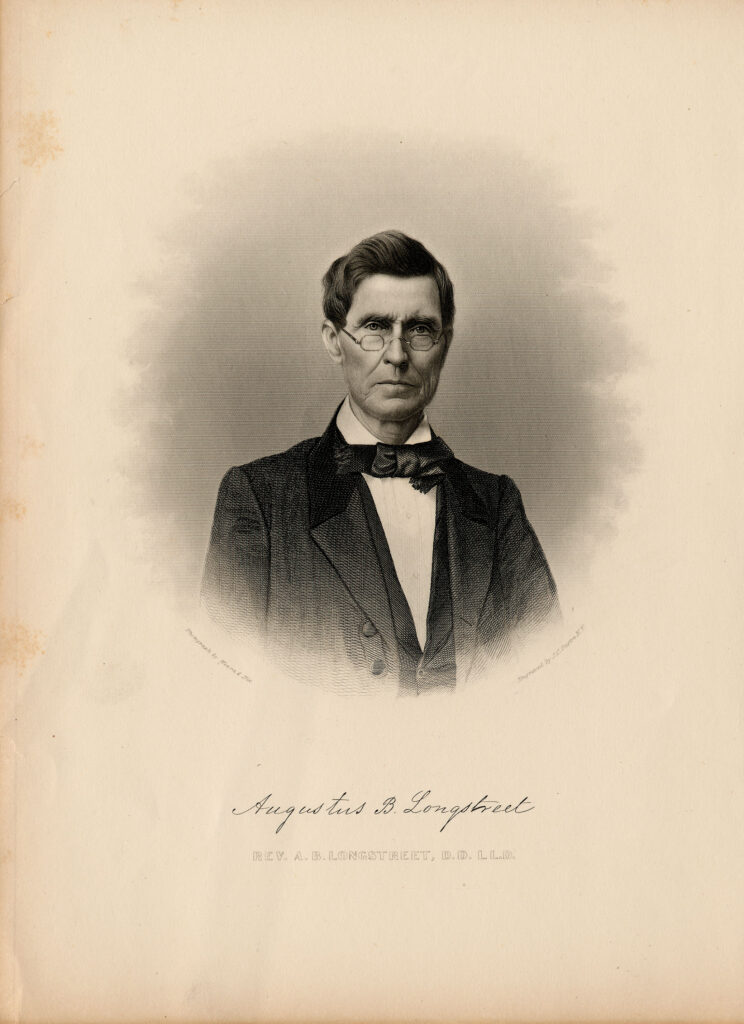

The earliest and most popular Georgia humorist was Augustus Baldwin Longstreet, whose 1835 collection, Georgia Scenes, helped define the southern humor genre. Like much southern humor, Longstreet’s sketches are often brutal; in “The Fight” town rowdies engage in bloody combat, which is described in graphic detail. In “The Horse-Swap” an unsuspecting man is swindled when he trades for a horse with a festering saddle sore (a tale that influenced William Faulkner’s novel The Hamlet). “The Gander Pulling” describes a small-town contest in which young men on horseback compete to be the first to pull the head off a goose suspended from a tree.

Another Georgia humorist was William Tappan Thompson, whose charming narrator-farmer, Major Jones, writes letters to a city newspaper editor about life in rural Georgia. Thompson’s sketches, written mainly during the 1840s, are unusually gentle for the southern humor tradition. Bill Arp (Charles Henry Smith) wrote satirical newspaper columns later in the century (the mid-twentieth-century Piney Woods Pete was his successor). Tales by enlaved people preserved by Joel Chandler Harris in the Uncle Remus stories show how African Americans practiced the genre as well.

Readers who found southern humor too vulgar could turn to other kinds of writing. One alternative was the sentimental fiction of Georgia-Alabama novelist Augusta Jane Evans Wilson. The strong heroines at the center of her novels Macaria (1864) and St. Elmo (1866) contrasted markedly with the female characters in other works of the time and later influenced Margaret Mitchell’s portrayal of Scarlett O’Hara. Evans’s fiction is marked by melodrama. In the first thirty-one pages of St. Elmo (one of the most popular novels of the nineteenth century), the main character, Edna Earle, sees a man killed in a duel, the man’s wife die of paralysis, her own grandfather die of old age, and a baby and others killed in a train wreck.

The end of the Civil War (1861-65) marked a clear point of division in the state’s history and literature. Joel Chandler Harris, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, wrote an impressive variety of stories, novels, and sketches. He is best known for his Uncle Remus tales. Uncle Remus: His Songs and His Sayings appeared in 1880 and was followed over the next twenty-seven years by four more volumes. Some regard these tales as sentimental or racist, but many of them were written with a psychological perceptiveness and a real desire to preserve these remnants of enslaved African culture.

Another late-nineteenth-century Georgia writer was the realist Will Harben, who focused on poor Georgia whites and who dedicated to Harris one of his best-known books, Northern Georgia Sketches (1900). Harris, along with William Tappan Thompson, Bill Arp, Henry W. Grady, and others, worked during the late decades of the nineteenth century at the Atlanta Constitution, a newspaper that played an important role in the development of the state’s literature.

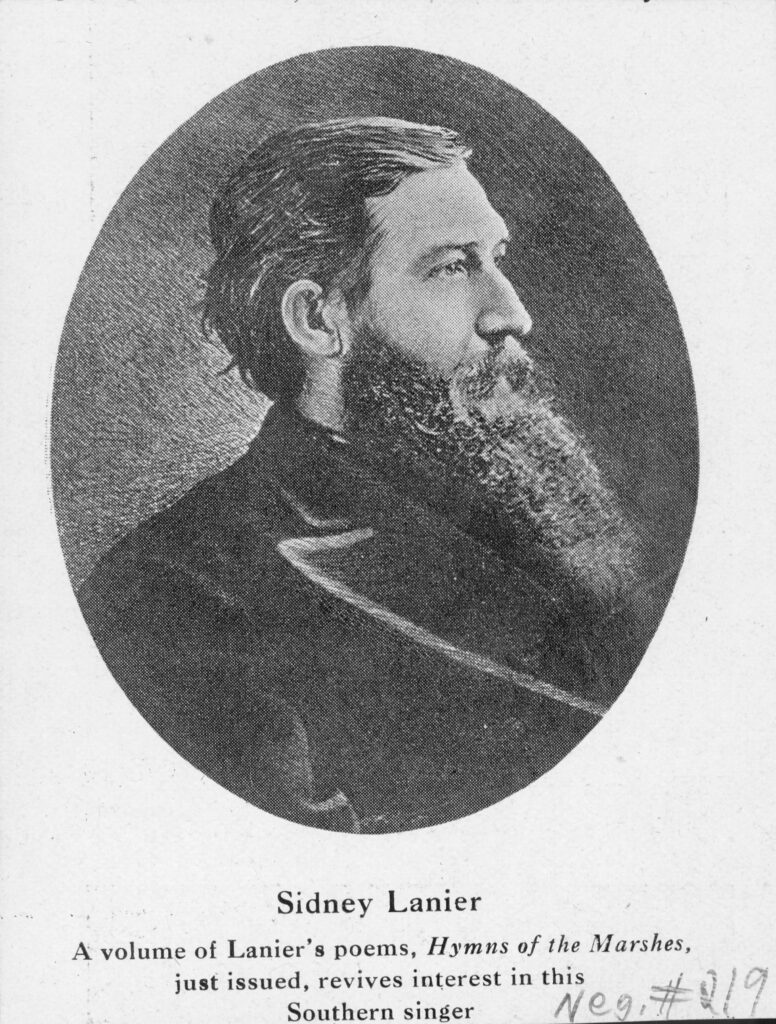

Georgia’s leading nineteenth-century poet was Sidney Lanier, a Civil War veteran and accomplished musician. Lanier’s total poetic output amounts to just under 100 poems. Though not often anthologized today, he wrote several poems of considerable merit—especially “The Marshes of Glynn” (1879) and “The Song of the Chattahoochee” (1877). The success of these poems stems from the natural music of Lanier’s language and his ability to evoke the emotional impact of landscape.

In “The Song of the Chattahoochee” Lanier playfully manipulates meter, line length, and geographical place-names in a poem that imitates the sound of the rippling waters of the upper Chattahoochee River and recalls the geography of north Georgia. “The Marshes of Glynn” is a more introspective study of coastal landscape, and is considered by many people to be one of the finest poems of the nineteenth century. Written in the tradition of Walt Whitman and the transcendental writers Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry Thoreau, the poem impressionistically describes the tidal marshes near Brunswick, linking the changing tides and nightfall to human consciousness and the soul. Lanier’s poems “Corn” (1875) and “Thar’s More in the Man Than Thar Is in the Land” (1869) celebrate the importance of agriculture, and they contributed to the debate between the New South and the agrarian South at the end of the nineteenth century. Lanier also wrote a novel, Tiger-Lilies (1867), based partially on his experiences in the Civil War.

The Twentieth Century

Throughout the twentieth century, Georgia writers continued to explore their changing region and gradually began to enter into the life of a larger national and world community. Not every Georgia-born writer wrote about Georgia. Conrad Aiken, for example, born in Savannah, and the Harvard University roommate of poet T. S. Eliot, produced distinguished poetry, fiction, and criticism that showed little outward interest in the state. Other writers were directly concerned with Georgia: Margaret Mitchell, Erskine Caldwell, and Byron Herbert Reece are among them. Many writers, such as Carson McCullers and Flannery O’Connor, viewed their state as a microcosm and wrote both as native citizens and as inhabitants of a larger world.

Race was clearly a central issue for twentieth-century Georgia writers. Encouraged by the slow but undeniable progress in Atlanta and other cities, and by the Harlem Renaissance in the North, African Americans in Georgia began to write in every genre. Several public leaders were among them. The educator and philosopher W. E. B. Du Bois, on the faculty of Atlanta University (later Clark Atlanta University) from 1897 to 1910, encouraged the development of a cultural and political identity for Blacks in Atlanta and the nation. His 1903 book The Souls of Black Folk remains an important study of race and racism in American society. Walter White, chief secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People between 1929 and 1955, wrote two novels, Fire in the Flint (1924) and Flight (1926), a distinguished autobiography (A Man Called White, 1948), and several studies of racism in America.

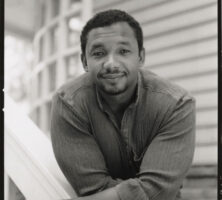

African American writers faced a complicated set of issues. Foremost among them were the question of identity and the role African Americans should play in the oppressive society in which they lived. Such writers as Jean Toomer, Frank Yerby, Georgia Douglas Johnson, and John Oliver Killens addressed these concerns. Toomer’s novel Cane (1923) is a powerful celebration of the Black folk culture of rural Georgia. Killens in his novel Youngblood (1954) examines the forces that confront a young Black man in a racist society, and Yerby in his early stories is similarly concerned, though in his later career he became a best-selling romantic novelist. Johnson wrote of these issues from a woman’s perspective in poetry and plays that deserve to be better known. More recent writers, such as Alice Walker, Tina McElroy Ansa, John Holman, Tayari Jones, and Anthony Grooms, have continued to explore similar topics.

Race was also important for white writers. Among them, Lillian Smith gave the issue the most controversial treatment for her time. Her novel Strange Fruit (1944) explored racism and interracial love in a small south Georgia town, and her nonfiction work Killers of the Dream (1949) graphically described the moral dilemmas posed by life in the pre–civil rights South. Other white writers were still attempting to come to terms with the relationship of whites and Blacks in a society predicated on racial separateness. Their struggles, and their ambivalence, could produce powerful literature. Flannery O’Connor’s short story “The Artificial Nigger” (1957) is a penetrating study of racial isolation from a white perspective. Byron Herbert Reece’s second novel, The Hawk and the Sun (1955), and Carson McCullers’s novel The Member of the Wedding (1946) explore the issue, as do such later novels as Erskine Caldwell’s In Search of Bisco (1965), Judson Mitcham’s The Sweet Everlasting (1996), and James Kilgo’s Daughter of My People (1998).

Among the notable works by Georgians during the 1920s and 1930s were novels by women. Frances Newman, a Georgia Institute of Technology librarian, wrote two highly stylized novels about southern women in a male-dominated society: The Hard-Boiled Virgin (1926) and Dead Lovers Are Faithful Lovers (1928). Caroline Miller’s Lamb in His Bosom (1933) records the travails of a young mother in the isolated wiregrass region of south Georgia. It won the Pulitzer Prize.

Three years later another Georgia novel, Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind (1936), also won the Pulitzer. This perennially best-selling book was made into a film widely regarded as a classic of its era. Mitchell sought to present a historically accurate account of the nineteenth-century South and the place of women in a male-dominated society defeated in war. Her descriptions of Tara, the plantation home of the O’Hara family, and of the main character, Scarlett O’Hara, have become indistinguishable in the popular imagination from the historical reality of the Old South. Despite a number of brilliant scenes, many critics argue that Gone With the Wind is marred by stereotyped characters and a flawed vision of southern history.

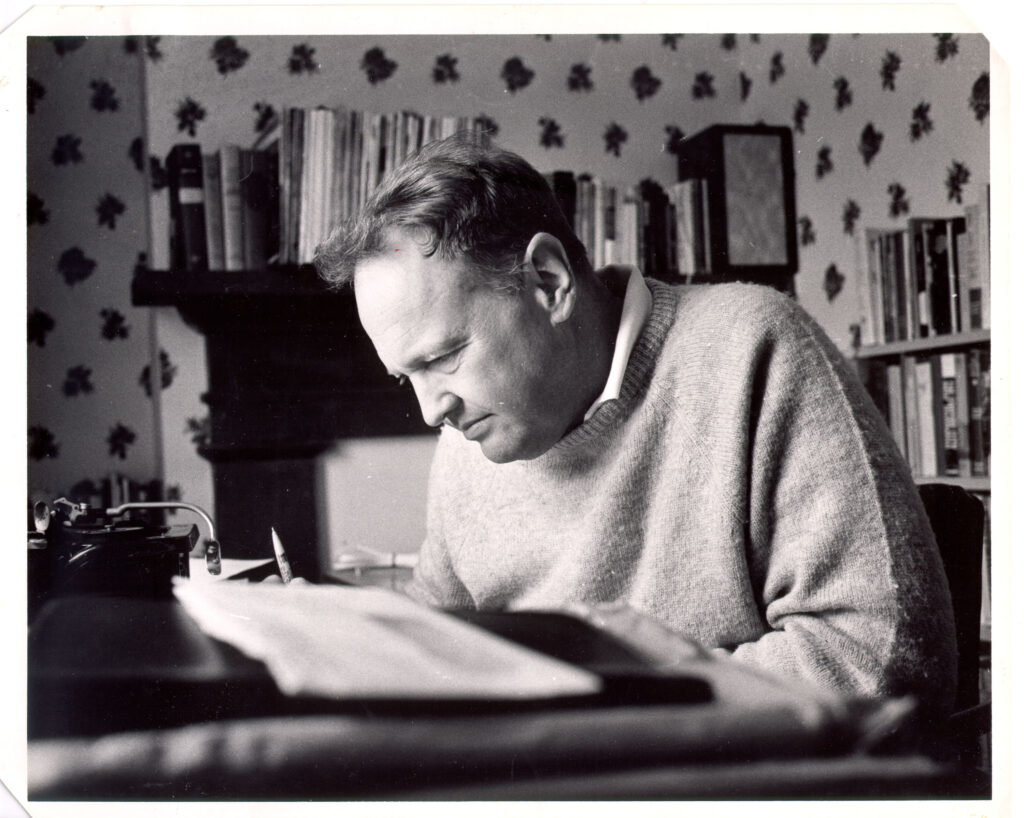

Perhaps the best-known Georgia writer during the 1930s was Erskine Caldwell. His novels Tobacco Road (1932) and God’s Little Acre (1933) offered controversial studies of poor whites in eastern Georgia during the depression. In these novels Caldwell combines naturalistic realism with social criticism, dark humor, satire, and graphic sexuality. In its concern with the plight of poor farmers, his novel Tobacco Road in particular deserves to stand alongside John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath and Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying. A play based on Tobacco Road had a long and controversial run on Broadway. Among Caldwell’s other important books are American Earth (stories, 1931), Kneel to the Rising Sun and Other Stories (1935), Trouble in July (novel, 1940), and You Have Seen Their Faces (documentary narrative, 1937), a collaboration with the photographer Margaret Bourke-White.

The publication of The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter in 1940 by twenty-three-year-old Carson McCullers of Columbus marked the emergence of another major figure. McCullers’s wistful, elegiac portraits of isolated, repressed, and psychologically tormented individuals in small southern towns gained her a national reputation. She followed her first novel with Reflections in a Golden Eye (1941), The Member of the Wedding (1946), and a series of short stories. By the time she published what many consider her best work, The Ballad of the Sad Café (1951), her health was failing, and her career was nearly finished.

Less well known, and more traditional in his use of regional subjects and literary forms, was Byron Herbert Reece, a north Georgia mountain poet and novelist. His melancholic, dark lyrics about disappointment in love and emotional and physical suffering also express a strong devotion to the region of his birth. His novels Better a Dinner of Herbs (1950) and The Hawk and the Sun (1955) are evocative portrayals of modern life and its problems in small-town north Georgia.

Modern Georgia

With the civil rights movement, the growth of Atlanta into an international city, the crisis in farming, and the dawning of the information age, Georgia plunged headlong into modernity. Writers in the state explore the receding past as a way of understanding their regional identity, examine the difficulties of adjusting to a rapidly changing society, or chronicle those scenes and characters that the modern world threatens to push out of the way. No longer does the state’s regional character seem a mark of separateness.

Such writers as Raymond Andrews, Olive Ann Burns, Terry Kay, Ferrol Sams, and Alice Walker turn to the past to recover and define their origins, to place themselves more securely in the modern landscape. Andrews in particular sought to preserve a folk and cultural tradition in his Muskhogean trilogy, a humorous, sweeping chronicle of Black life in a small rural county of the state. Olive Ann Burns seemed similarly concerned with recovering the details of life long past in her novel Cold Sassy Tree (1984). Donald Windham’s stories about Atlanta in The Warm Country (1962) and his memoir about growing up in the city, Emblems of Conduct (1964), Terry Kay in The Year the Lights Came On (1976), Ferrol Sams in Run with the Horsemen (1982) and Whisper of the River (1984), and Warren Leamon in Unheard Melodies (1990) engage in a similar process of preservation.

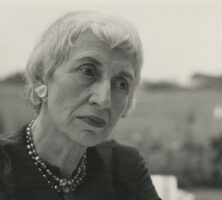

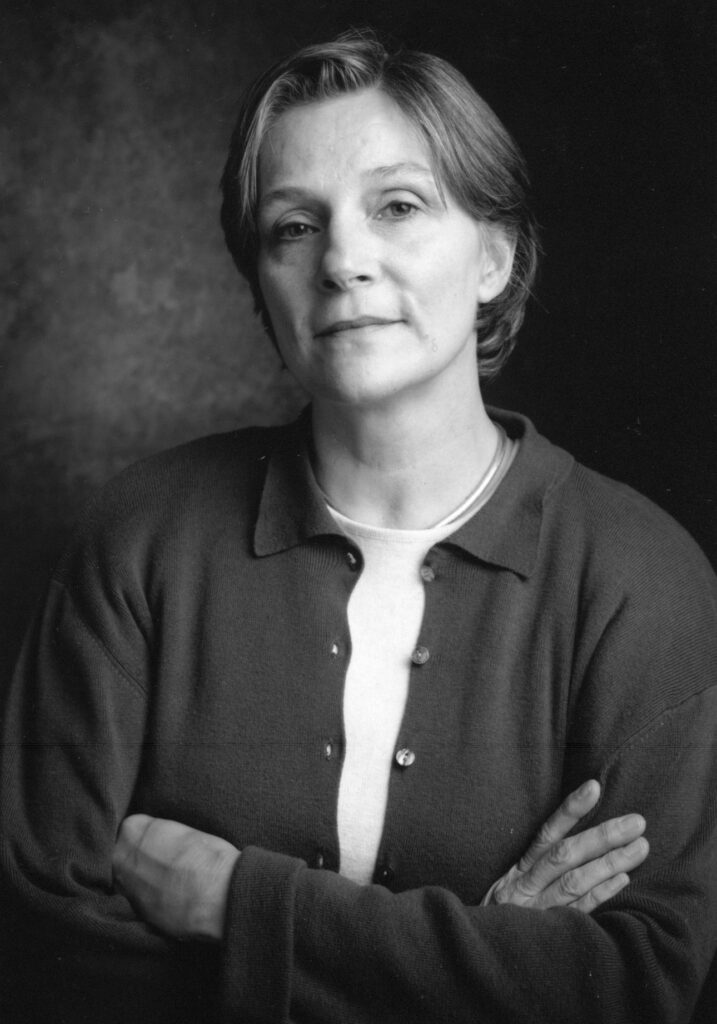

Four writers have dominated the literary landscape of modern Georgia. Flannery O’Connor, who died in 1964, was a major figure in American writing. Her characters, her use of the grotesque, her fusion of comedy and tragedy, her dark vision of a fallen modern world, and the moral structure of her plots made her one of the century’s finest writers of short fiction. She took the change occurring in Georgia and the South as a major theme, though she used it as a metaphor for larger concerns with the human condition. For O’Connor, the South and the modern world had become a place of abandoned faith and lost souls. Alice Walker, Harry Crews, and Marion Montgomery are three of a number of Georgians she influenced. Her short novels, Wise Blood (1952) and The Violent Bear It Away (1960), and her story collections, A Good Man Is Hard to Find (1955) and Everything That Rises Must Converge (1965), are remarkable achievements.

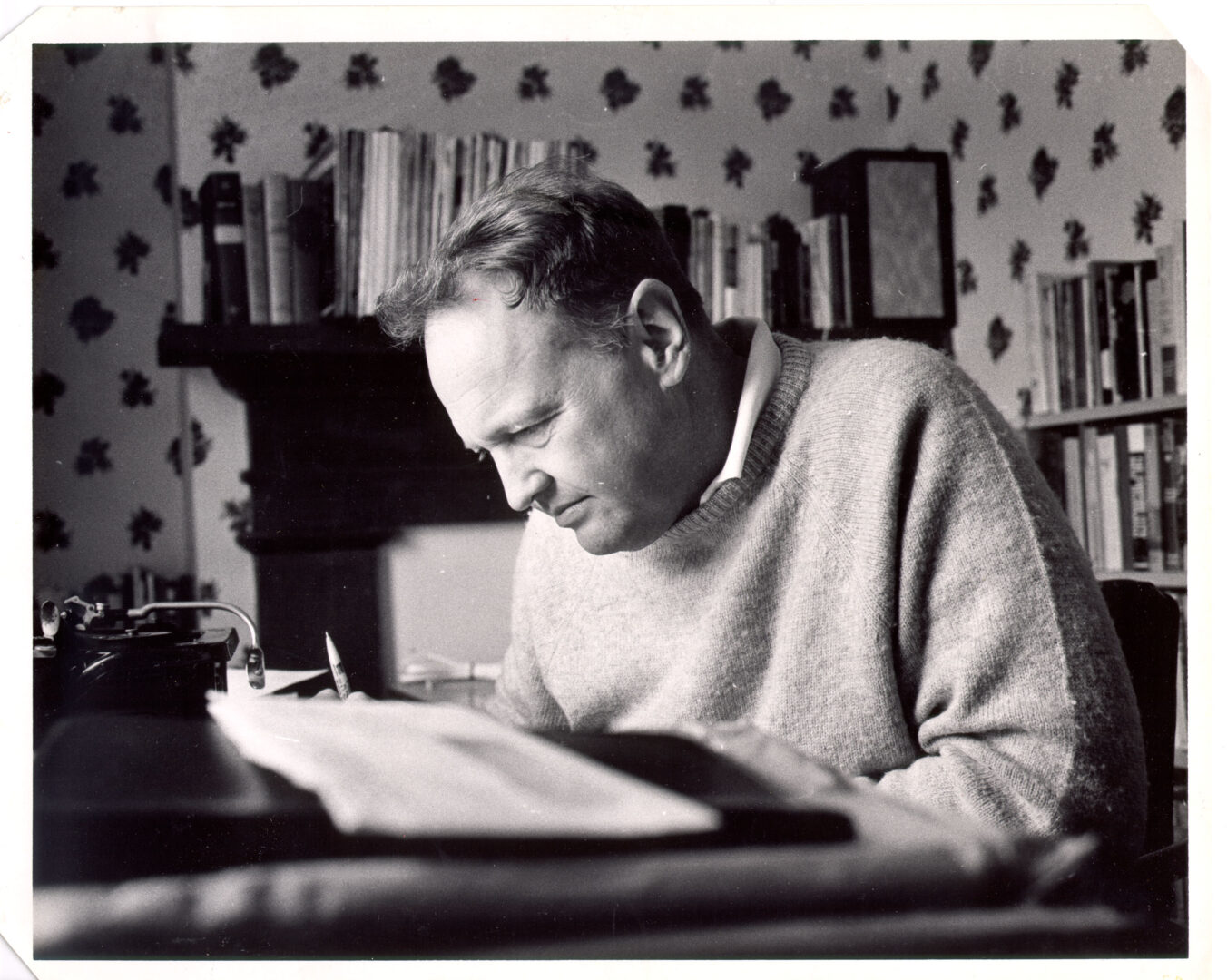

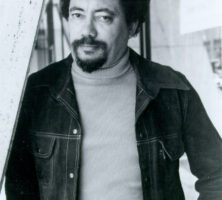

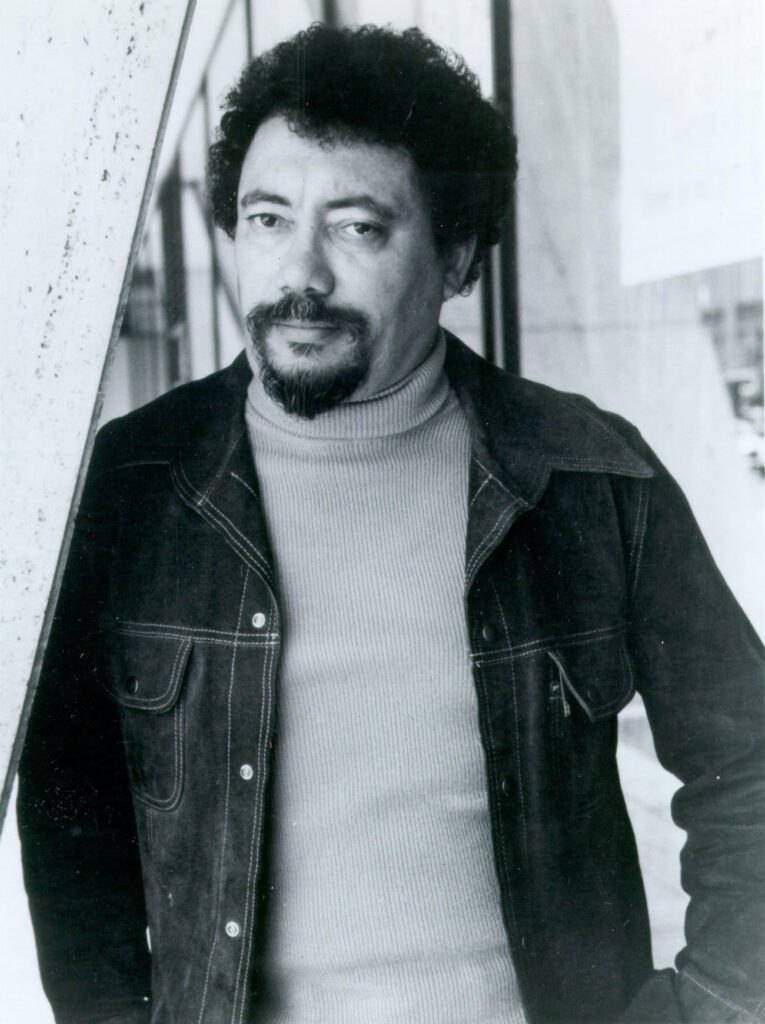

James Dickey’s poetry, novels, and literary criticism made him a dominating figure in American writing during the 1960s and 1970s. He began publishing in the 1950s, but the appearance of a ten-year retrospective of his poetry in 1967 brought him to the attention of a national audience. For Dickey, intensity of physical and imaginative experience was a source of redemption and identity in the modern world, whether he was writing, sitting in a tree house, floating in a rowboat at night, or contemplating images from his own imagination. Redemption through action is one of his major themes, and it lies at the center of his 1970 novel, Deliverance (which considers the ironic links of southern progress and southern traditions), and his final novel, To the White Sea (1993).

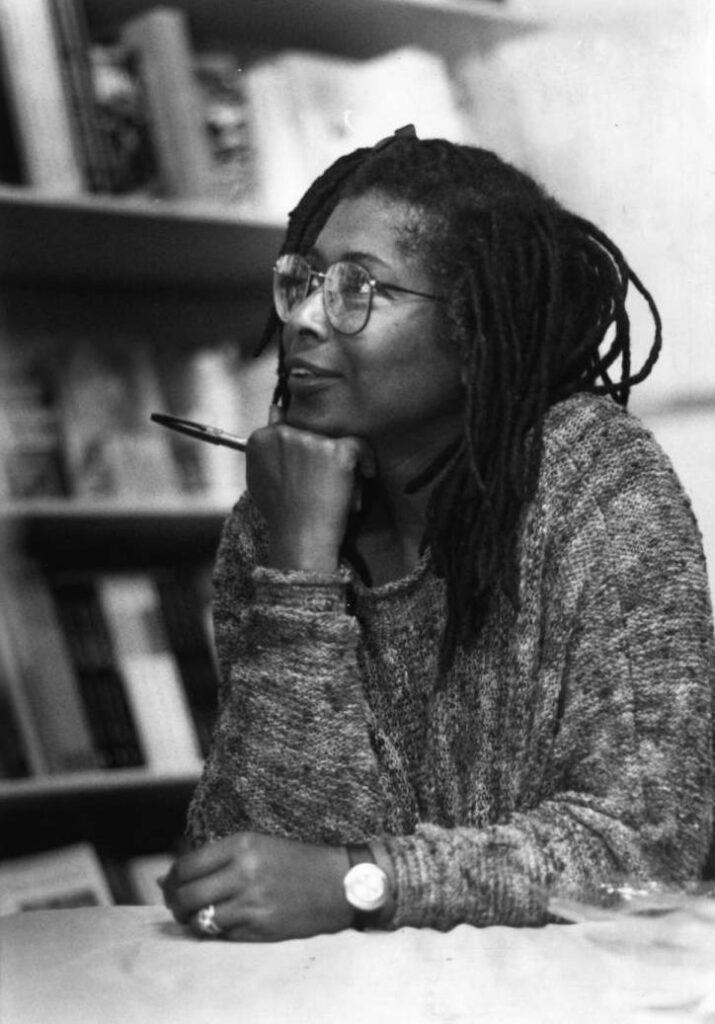

A third important figure is Alice Walker. She has written from a number of perspectives, exploring the nature of life for Black Americans in the modern world and examining the plight of women—especially women of color—in a male-dominated society. Her style is varied, ranging from traditional realism to experimental stream-of-consciousness and postmodern techniques. Her novel The Color Purple (1982), for instance, is told through a series of letters. Early in her career she wrote from a traditional southern perspective that values tradition, kinship, and place. In The Color Purple, her characters find satisfaction by coming to terms with the place of their births, even with those men who have oppressed them. Yet in its concern with Africa, The Color Purple showed Walker’s growing global perspective. Her later work has ranged widely, covering such subjects as the sexual mutilation of women in Africa to the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center in September 2001. Among her important books are Meridian (novel, 1976), In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Womanist Prose (essays, 1983), and The Temple of My Familiar (novel, 1989).

The career of Harry Crews extends through the last three decades of the twentieth century and includes an impressive list of novels about marginal characters in the nether regions of the modern South. His perspective is darkly comic, and he often focuses on deformed or tormented characters (following in O’Connor’s tradition): a paraplegic wrestler in The Gypsy’s Curse (1974), a female body-builder in Body (1990), a failed college athlete who lives in a trailer park near the rattlesnake capital of the world in A Feast of Snakes (1976). Crews’s fiction advocates stoicism in the face of despair and defeat. His memoir A Childhood: The Biography of a Place (1978), about his early life as the son of a south Georgia sharecropper, is considered by many to be his best book.

Georgia Writers Today

Contemporary Georgia has produced an impressive group of poets and fiction writers. David Bottoms, Georgia’s poet laureate from 2000 to 2012, is one of the leading poets of the last thirty years, along with Edgar Bowers, Alfred Corn, Wyatt Prunty, Charlie Smith, Judith Ortiz Cofer, Kathryn Stripling Byer, Jericho Brown, Judson Mitcham, Chelsea Rathburn, and others. Rathburn succeeded Mitcham to become the state’s eleventh poet laureate in 2019.

In fiction, the novels of Pat Conroy, largely set outside Georgia, have gained a wide following, as have those of Anne Rivers Siddons and Joshilyn Jackson. Tayari Jones’s four novels, each set in and around Atlanta, have garnered numerous awards and critical acclaim. Charlie Smith’s fiction about torment, sex, and violence in the Deep South has also received national attention. Ferrol Sams gained a popular following with a trilogy of novels about life in early-twentieth-century Fayette County. Pam Durban’s stories and novels have established her as a leading writer of southern fiction, as have Mary Hood’s two short-story collections, How Far She Went (1984) and And Venus Is Blue (1986), and her novel, Familiar Heat (1995). Other notable contemporary fiction writers in Georgia include Tina McElroy Ansa, Janice Daugharty, Toni Cade Bambara, Frank Manley, Philip Lee Williams, Shay Youngblood, Anthony Grooms (especially his novel Bombingham, 2001), Greg Johnson, Michael Bishop, and others.

In nonfiction, Melissa Fay Greene with Praying for Sheetrock (1991) and The Temple Bombing (1996), James Kilgo with Deep Enough for Ivorybills (1988) and Inheritance of Horses (1994), and Janisse Ray with Ecology of a Cracker Childhood (1999) gained national followings.

In drama, Margaret Edson’s play Wit was produced on Broadway, made into an HBO film,and awarded the Pulitzer Prize for drama in 1999. One of the leading contemporary American dramatists has been Atlantan Alfred Uhry, whose plays, including Driving Miss Daisy (1987), The Last Night of Ballyhoo (1996), and Parade (1999), a musical based on the Leo Frank case, were produced on Broadway. His awards include the Pulitzer Prize for drama, a Tony award, and an Academy Award for the film version of Driving Miss Daisy. Plays by Pearl Cleage have also been widely performed.

Georgia writers have written about the same subjects that have interested writers across history and throughout the world: family, war, hardship, ambition, love and death, change, the search for knowledge and meaning. But Georgia has provided its writers with a context of history and geography, with social and cultural values, that give their work an identity grounded in time and place, a shared heritage and experience, which out of all the world’s literature and history make it distinctive and unique.