Dueling involved two combatants, with some intractable disagreement, who fought one another, often to the death. These engagements proceeded according to a predetermined set of rules and were usually waged with pistols.

An ancient European practice, dueling began in Georgia in the mid-eighteenth century. The last recorded duel in the state occurred in 1877, though Georgia had criminalized the practice in 1809. Dueling in Georgia was significant because it highlighted aristocratic southerners’ conception of honor, which in no small part led to secession and the Civil War (1861-65).

Origins, Practice, and Honor

Duels originated in medieval European society in accordance with chivalry, a social code that emphasized courtesy, courage, and martial prowess as the most essential qualities in a knight or male aristocrat. By imposing rules on violent confrontations in a society where lawlessness often seemed rampant, dueling was actually seen as a civilizing ritual. Practiced by some of the first European settlers in Georgia, dueling spread quickly throughout the colony. Georgia’s first recorded duel took place in December 1739, when a British officer wounded a compatriot in Savannah.

Duels occurred when one party issued a challenge, written or verbal, to another, usually in response to a perceived slight. Swords and pistols were the weapons of choice, although by the nineteenth century duelists usually opted for pistols. Seconds, or representatives of the dueling parties, organized these affairs, and when pistols were used, the antagonists fired at one another. Although the distance between the shooters was negotiable, shots were usually exchanged at close range, sometimes even as short as ten paces. Still, early nineteenth century pistols were notoriously unreliable, and often duelists simply wanted to prove their courage and hesitated to kill their opponents. Most duels, then, were not fatal and ended with (sometimes intentionally) wildly errant shots, compromises, or apologies. Nevertheless, many resulted in one or both of the combatants being maimed, mortally wounded, or killed outright.

While the 1804 duel between Alexander Hamilton—whose second, Nathaniel Pendleton, was a Georgian—and Aaron Burr in New Jersey is the most famous duel in American history, it was in the antebellum South that dueling became most ensconced in the social code. An accepted protocol by which duels were fought, known as code duello, largely defined the practice in the South. Dueling helped establish a community’s perception of an individual and played a critical role in an aristocratic society that placed a high value on personal honor.

In some respects, the southern conception of honor that precipitated so many duels also helped precipitate secession and the Civil War. By 1860 southern aristocrats had come to associate slavery with honor. Just as ignoring a challenge to a duel would court dishonor, so would letting abolitionists usurp the moral high ground in the national controversy over slavery. For this reason, many aristocratic southerners, at least initially, saw the Civil War as a large-scale version of a duel. Military confrontation was a test of courage that ultimately reflected both personal and sectional honor, and the war itself was to be fought according to an implicit set of gentlemanly rules, in the fashion of code duello. Although not fully implemented until 1864, northern “total war” policies came to represent a flagrant betrayal of the sacred code and, for many Confederate officers, a grievous breach of chivalric honor.

The Gwinnett-McIntosh Duel

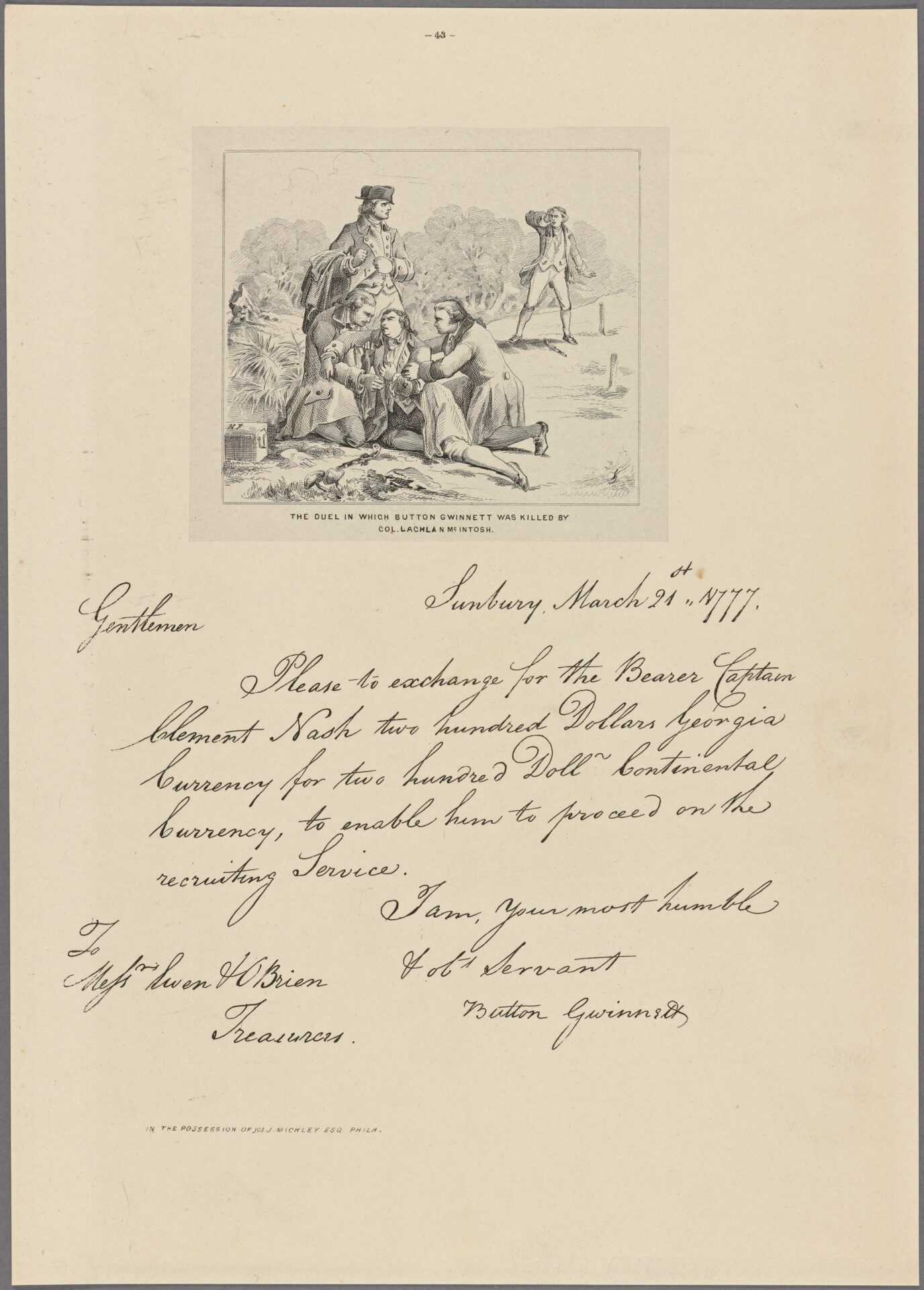

By the Revolutionary era, Georgia had become a hotbed for dueling. Despite the galvanizing effect of the war, highborn Georgians still resorted to pistols or swords to exorcise their social frustrations and resolve interpersonal feuds. Probably the state’s most famous duel occurred between Button Gwinnett and Lachlan McIntosh. McIntosh was a brigadier general in the Continental Army. After signing the Declaration of Independence, Gwinnett was a principal contributor to the drafting of the Georgia Constitution in 1777. Soon after, he was elected president and commander-in-chief of Georgia and decided to lead an expedition to claim Florida for the United States.

Under the rules of the Georgia General Assembly, however, Gwinnett lacked the authority to appropriate McIntosh’s brigade, which had been designated for the Continental Army. Undermanned, Gwinnett’s mission was a disaster, and he returned home only to be ousted from his position as commander-in-chief. During a subsequent convention of the General Assembly in Savannah, McIntosh called Gwinnett a “Scoundrell” and a “lying Rascal.” Accordingly, Gwinnett challenged McIntosh to a duel, and the next morning, on May 16, 1777, they squared off just south of Colonial Park Cemetery with pistols at a distance of only twelve feet. McIntosh mortally wounded Gwinnett on the first shot. Accused of murder, McIntosh turned himself in to the authorities and was indicted and tried, only to be acquitted and released.

The Stark-Minis Duel

Another famous duel in Georgia history is notable for the odd circumstances under which it was fought and its eschewal of conventional dueling etiquette. In 1832 James Stark, a member of the General Assembly, passed Philip Minis, a Jewish doctor, on a Savannah street. According to one witness, Stark directed anti-Semitic slurs at Minis, who promptly challenged Stark to a duel. After retracting an apology, Stark reiterated his anti-Semitic slurs and asserted that Minis “was not worth the powder and lead it would take to kill him.” The men quickly agreed to a duel.

Stark wanted to fight immediately, but Minis wanted to wait at least one day. On the day of the challenge, Stark and his second went to the dueling ground although Minis had never agreed to be there. When Stark returned, unsatisfied, to town, he called Minis a coward in public. A peaceful resolution now impossible, Minis entered the bar at the City Hotel sometime later and proclaimed Stark a coward. According to Minis’s sister, both men drew their pistols, but Minis fired first, killing Stark instantly. The encounter was unusual, but, since both men pulled their pistols to resolve an affair of honor, many have regarded it as a duel nevertheless. The jury appointed to decide Minis’s fate apparently agreed. Though many of Stark’s partisans maintained that he was guilty of murder, Minis was acquitted.

The Anti-Dueling Movement and the Decline of Dueling in Georgia

Georgia was slow to suppress dueling, even by regional standards. In 1809 Governor David B. Mitchell—who had himself killed a political opponent in a duel just five years earlier—signed legislation criminalizing dueling. However, the public remained sympathetic to the practice, and few duelists were prosecuted. If anything, by regarding duels as “purely private affairs” and by failing to adhere to the law as it was expressly written, state courts implicitly encouraged the practice.

Not until 1826 would Georgia citizens establish a significant official body—the Savannah Anti-Duelling Association—to turn the tide of public opinion against duelists and insist that local officials enforce existing statutes prohibiting the violent ritual. In establishing the Association, prominent Savannahians denounced dueling as “a violation of all law, both human and divine.” The Savannah Anti-Duelling Association launched an effective essay campaign condemning the practice, and duels became less frequent by 1830.

Predictions of the practice’s demise proved premature, however. Members of the U.S. Congress dueled regularly in the decades before the Civil War, and in 1838 Congress proposed, but eventually failed to pass, a constitutional amendment banning these so-called affairs of honor. In the 1840s, the Savannah Anti-Duelling Association’s influence began to decline, and the frequency of duels increased once more.

Ultimately, it would take the Civil War to virtually eradicate dueling in the South. Code duello had primarily been the obsession of a planter aristocracy that was seriously injured by the war. Northern total war policies had made southern allusions to honor—already nebulous and anachronistic—seem almost entirely obsolete in a rapidly modernizing nation reunited on northern terms. Besides, the approximately 752,000 lives claimed by the war made blood spilled in the name of the code seem all the more superfluous. The nation, the South, and even Georgia, had already had enough of dueling. Still, the last known duel on Georgia soil would not occur until 1877.

The last duel between Georgians, on the other hand, did not occur until 1889. Fought just over the state line in Alabama, this “Calhoun-Williamson affair” was a subject of great popular interest. Patrick Calhoun and J.D. Williamson, both prominent figures in the state’s railroad industry, agreed to duel after an exchange of insults. When the parties finally convened safely out of the reach of law enforcement, they stipulated that five shots from hammerless Smith & Wesson pistols could be used if necessary. Williamson misunderstood the stipulations and, when the word to fire was given, emptied his clip as quickly as possible. All of his shots went harmlessly errant. Calhoun, who had only fired one errant shot, demanded his opponent retract his previous insult. After Williamson refused, Calhoun fired his four shots into the air. Both men apologized to each other, and the parties returned home unharmed. Dueling was, at last, extinct among Georgians.