Immigrants to colonial Georgia came from a vast array of regions around the Atlantic basin—including the British Isles, northern Europe, the Mediterranean, Africa, the Caribbean, and a host of American colonies. They arrived in very different social and economic circumstances, bringing preconceptions and cultural practices from their homelands. Each wave of migrants changed the character of the colony—its size, composition, and economy—and brought new opportunities and new challenges to the people already there. A majority of the immigrant white population traveled to Georgia because of the availability and cheapness of land, which was bought, bartered, or bullied from surrounding Indians: more than 1 million acres in the 1730s, almost 3.5 million acres in 1763, and a further cession of more than 2 million acres in 1773.

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

From Europe

During the Trusteeship (1732-52), the overwhelming majority of Georgia immigrants—more than 3,000 in number—arrived from Europe. Around two-thirds of these pioneers were funded by the Trustees, who offered them a passage across the Atlantic, provisions for one year, tools, and a tract of land in return for their labor.

Print from Von Reck Archive, Royal Library of Denmark, Copenhagen

After 1752, under the headright system, every settler was entitled to 100 acres of land, plus 50 additional acres for each member of the settler’s household, including enslaved people and indentured servants. (In 1777 the initial allotment per settler changed to 200 acres.) All settlers—men and women—could receive up to 1,000 acres of land through a headright grant. The headright grant was a primary mechanism for distributing land throughout royal rule and early statehood.

Initially the settlers tended to congregate according to their ethnic origins. Highland Scots settled a Celtic outpost at Darien on the southern frontier. Lutheran Salzburgers swiftly organized a productive and dutiful township at Ebenezer to the north. English folk, many of them Londoners, dominated Savannah and its surrounding villages, along with a large number of Rhineland Germans and a few Lowland Scots. In and around these regional settlements were smaller enclaves of immigrants, including Spanish-speaking Sephardic Jews, French-speaking Swiss, pious Moravians, Irish convicts, and a handful of Piedmont Italians and Russians.

Following an unpleasant and often crowded Atlantic passage, the immigrants’ culture shock upon arriving in Georgia was intensified by the unusual makeup of the population. Migrating to the colony was a perilous undertaking, and around a third of the settlers had died by 1752. Most of these deaths were caused by malaria and typhoid, diseases that thrived around the swamps and river deltas of the Lowcountry and typically afflicted settlers in their first sweltering summer. As a result of this mortality, known as “seasoning,” the population struggled to grow naturally.

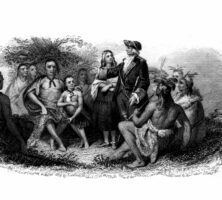

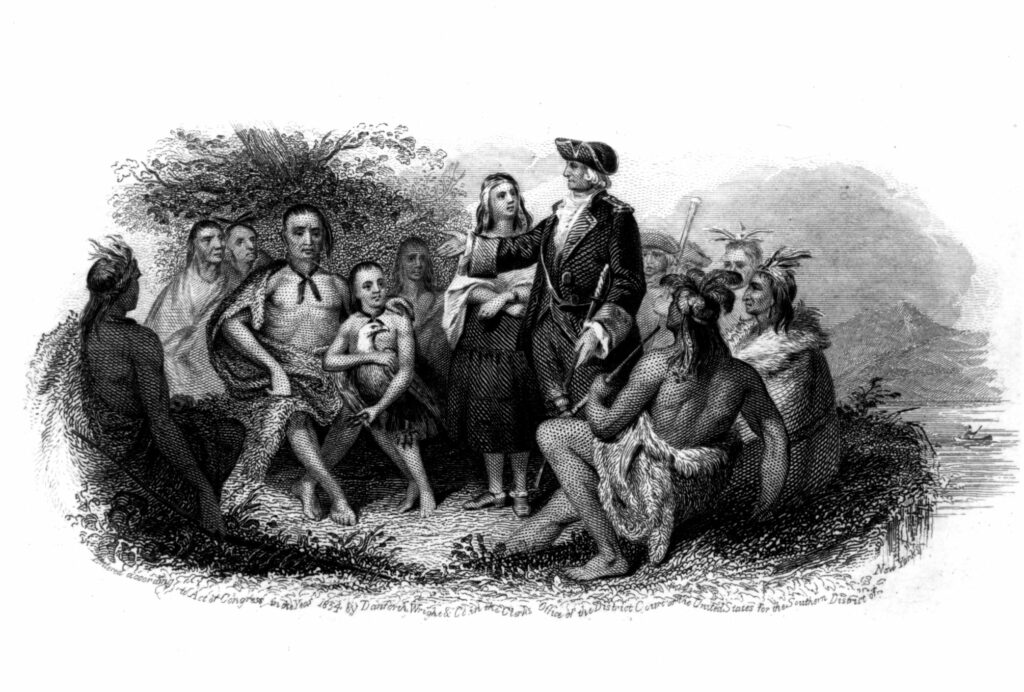

Fertility was also stunted by the fact that males outnumbered females two to one in these early years, while children accounted for only about a quarter of the new arrivals. Although many settlers decided to abandon the colony in light of these hazards, and many Malcontents complained vociferously, other survivors improvised and adapted to their new circumstances. The scarcity of females forced many settlers to overlook ethnic differences. Lutheran Salzburgers reluctantly married Reformed Rhinelanders, while Highland Scots, Irish, and French Swiss proved equally willing to hurdle linguistic and cultural obstacles in the quest for marriage, and more important, household economy. Sephardic Jews intermarried with Christian women, and many British men (most of them Indian traders) formed expedient unions with Creek females.

Kinship contacts and common interests began to tie Georgia’s early migrants together in the 1740s. Anglo-German links, for instance, were more amiable in the aftermath of the frightening war with Spain that had forced many coastal settlers to flee inland. After James Edward Oglethorpe’s victory at Bloody Marsh repulsed the Spaniards on July 7, 1742, the former refugees sent letters to Salzburg families thanking them for their kindness and including coffee and silk ribbons as tokens of their gratitude.

From Other Colonies and Africa

The pattern of settlement changed dramatically with the arrival of royal control in Georgia (1752-76). Although plenty of settlers continued to stream into Georgia from the Old World, the bulk of white immigrants now came in a series of waves from other British American colonies, attracted by the prospect of cheap and fertile lands. Of those newcomers who applied for land, and stated where they had migrated from, about two-thirds had arrived from the Carolinas, while about a fifth came from other Atlantic colonies—especially the Caribbean and the Chesapeake. The remainder hailed from the British Isles, with particularly strong representation from northern Britain and northern Ireland.

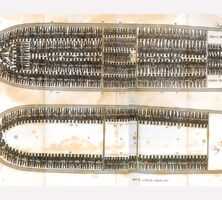

American settlers who flooded into Georgia tended to be young and brought enough women and children to offset imbalances within the population. Because they were familiar with the environment, they suffered less severely from “seasoning.” They also forcibly brought with them thousands of enslaved Africans and, together with earlier settlers who shared their appetite for plantation labor, imported thousands more via the Atlantic slave trade. As a result, Georgia’s colonial population leaped from an estimated 3,500 in 1752 to around 29,000 in 1773.

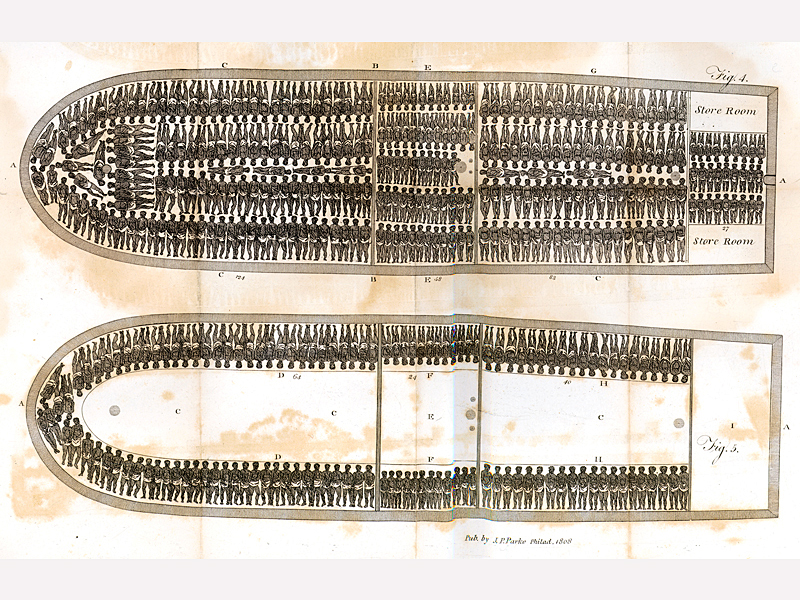

From The History of Rise, Progress & Accomplishment of the Abolition of the African Slave-trade by the British Parliament, by Thomas Clarkson

In the first wave, most of the seaboard region was claimed by settlers hailing from South Carolina and the West Indies during the 1750s. Slavery soon dominated the Lowcountry landscape, and as had already happened elsewhere on the mainland, provided a key rationale for integrating immigrants on the basis of their skin color. Although a significant Congregational township was settled at Midway, which quickly became prosperous, immigration declined with the outbreak of the Seven Years’ War (1756-63). The global conflict discouraged communities and individuals from risking a dangerous Atlantic voyage. More specifically, the lack of military protection in Georgia was a source of great consternation, since the province was sandwiched between the three great warring European powers and two restless Indian confederacies.

A second wave of royal-era migration began in the 1760s, with settlers who were more diverse in origins and ambitions than the plantation-oriented first wave. Although adventurous individuals and lone families poured in, most new arrivals belonged to larger communities. Some came for religious reasons, like the Quakers from North Carolina who claimed land in the township of Wrightsborough in 1768. Other groupings were occupational: in 1764 a number of shipmates in the Royal Navy, including the captain, first lieutenant, surgeon, and a number of “servants” who may well have been crew members, decided to settle on the Great Ogeechee River, along which they acquired neighboring tracts of land.

Georgia’s leaders, fearful of becoming overrun by unruly single white males, battled doggedly to ensure that their preferred brand of settler was encouraged—what Governor James Wright described as “the Middling Sort of People, such as have Families and a few Negroes.” In the early 1770s, Surveyor-General Henry Yonge reported that only 3,000 “plantable” acres remained unclaimed, mostly in unattractive and far-off locations.

By the end of the colonial era, white Georgians were still intricately connected to the wider Atlantic world, through commerce and kinship, but most had come to view themselves as more than just relocated British subjects or insular communities. When the impulse to subscribe to a new republican identity seized the Eastern Seaboard in 1776, just enough of the colony’s diverse free settlers considered themselves “Americans” to take part in the American Revolution (1775-83). During the conflict, thousands of opportunistic enslaved people and disaffected Loyalists sought to reverse their earlier migration by fleeing the newly declared state. Immigration to Georgia would continue apace after the war’s end, but the first motley waves had already become an independent ocean.