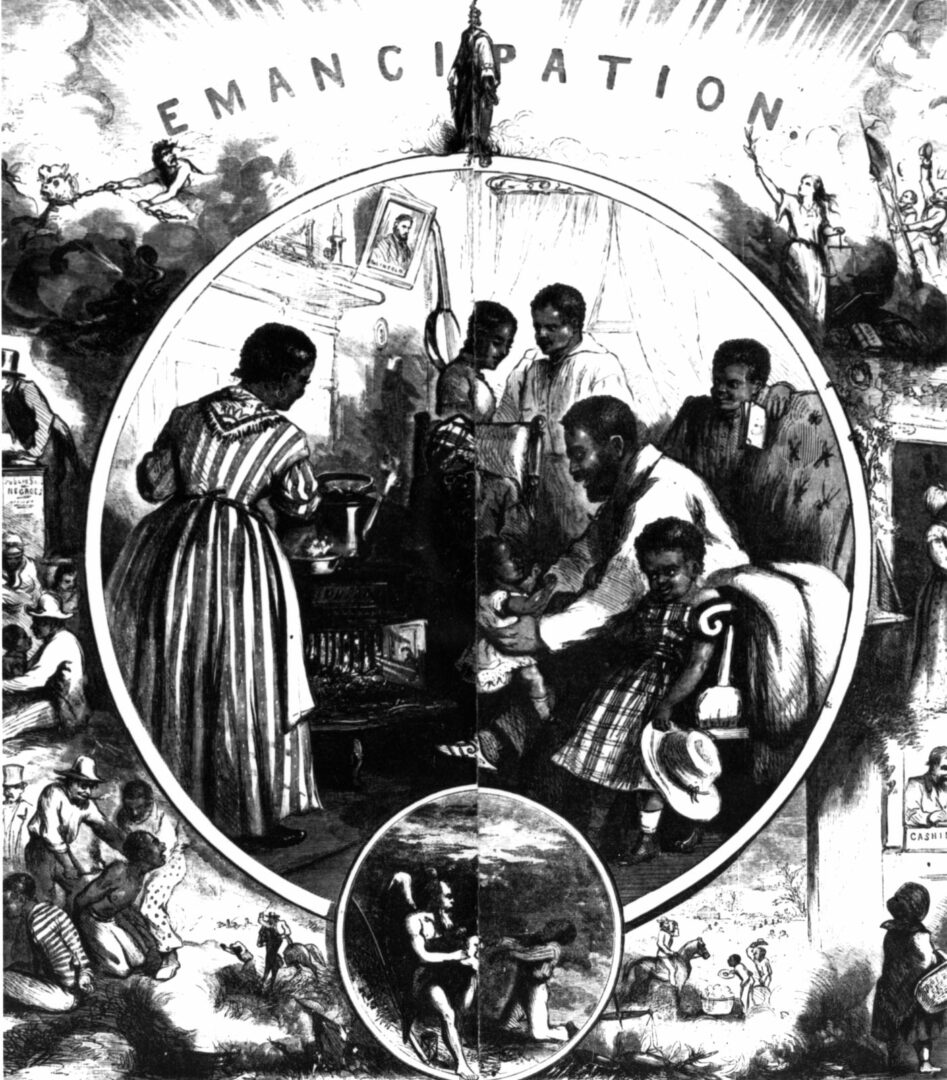

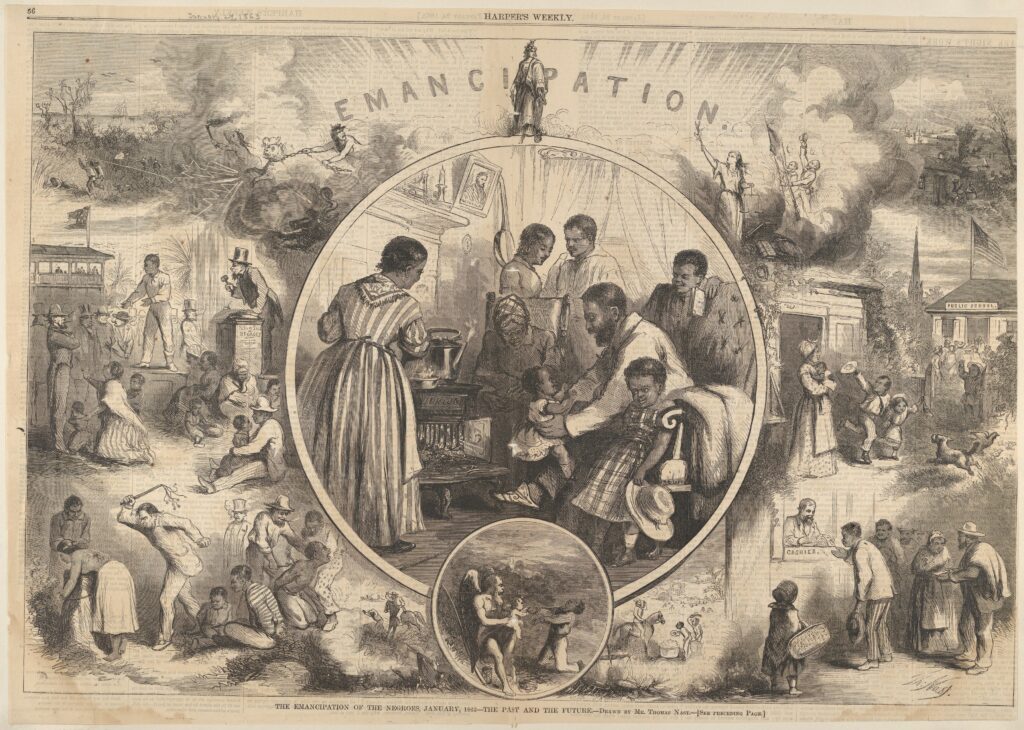

Emancipation did not come suddenly or easily to Georgia. The liberation of the state’s more than 400,000 enslaved African Americans began during the chaos of the Civil War (1861-65) and continued well into 1865.

Emancipation also demanded the reconfiguration of the full range of social and economic relations. What would replace slavery was unclear. Freedpeople, ex-slaveholders, and the Northerners responsible for enforcing freedom had their own ideas about what the future should bring. Struggles between those competing visions punctuated emancipation in Georgia. In waging those battles, however, Black people and white laid the foundations for a new social order. Though fragile and incomplete, it rested on assumptions of universal freedom and civil rights.

Breaking the Chains

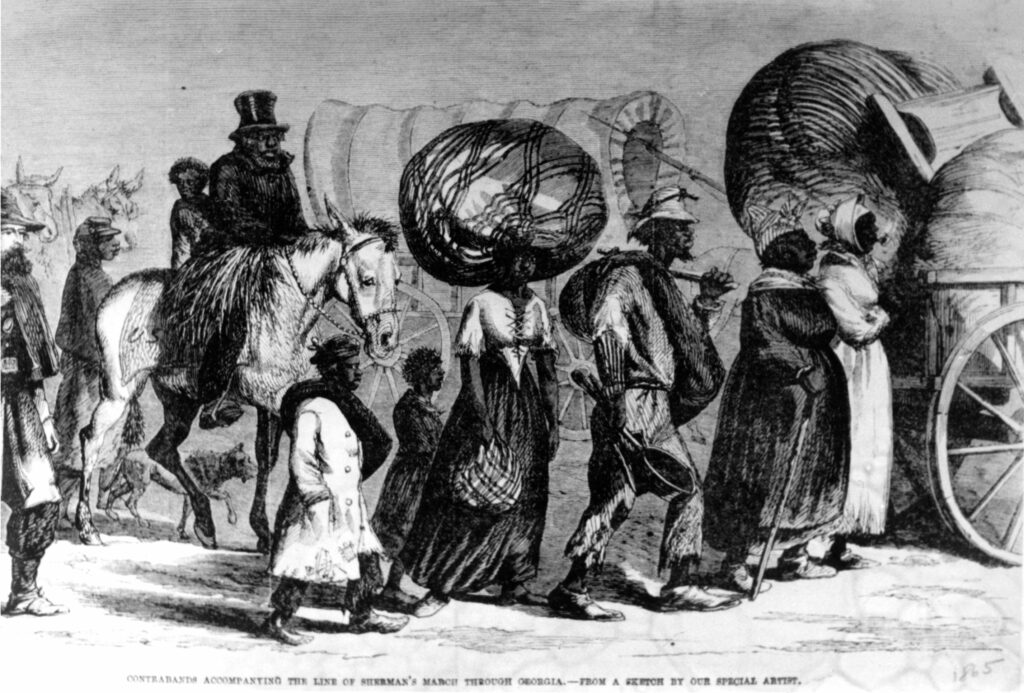

The liberation of Georgia’s enslaved population started piecemeal soon after the Civil War broke out in 1861 and then accelerated with the Confederate surrender in April 1865. While the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 provided a legal keystone for the liberation of enslaved people, it did not have a direct effect on the practice of slavery in Georgia. During the war, emancipation came largely at the hands of enslaved people determined to secure their own freedom. Some historians believe that 10,000 to 20,000 enslaved African Americans took advantage of the disruption caused by General William T. Sherman’s troops in their march to the sea and joined their columns; historical records indicate that as many as 7,000 of those may have still been with the Union forces as they arrived in Savannah.

After the war vastly more people played roles in emancipation. Union soldiers, most notably those of Sherman’s army in its march from Atlanta to the sea, liberated enslaved Georgians as they crossed the state. Slaveholders unintentionally spread the news by talking too freely of their nation’s loss in the presence of their servants. Enslaved people were always alert for the quietest whisper of freedom and eagerly shared whatever they learned, spreading word from quarter to quarter. But despite the efforts of both soldiers and the enslaved, weeks passed before the revolution penetrated the farthest corners of the state. Many slave owners sought to maintain the old system, and often only the threat of military force impelled them to release their bondsmen. Bondage lingered into the summer months of 1865, particularly in the more remote neighborhoods of southwest Georgia.

Imagining Freedom

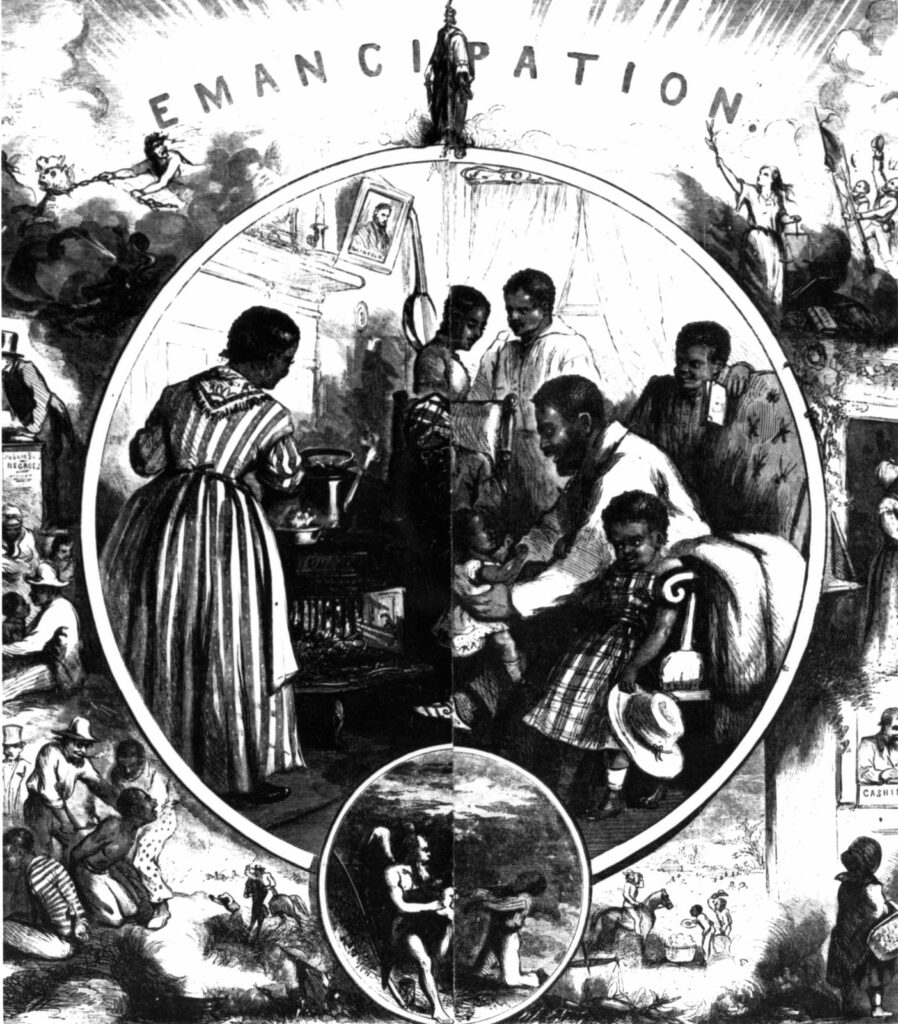

However and whenever freedom arrived, Black Georgians rejoiced in the opportunity to remake their lives. Some started small, with simple experiments to test their new status. They took a few hours off work to visit with friends, or they wore their finest clothes to promenade through city streets.

Others, determined to refashion their lives altogether, took bolder steps. They fled to the nearest military post or city (more than 6,000 fled to Atlanta and even more to Savannah), determined to escape forever the brutality that had scarred them in bondage. They struck out in search of family members scattered first by slavery and then by war and in search of new economic opportunities offered by cities and towns. A study of Dougherty County in southwest Georgia shows that the Black population of Albany, the county seat, grew by more than 75 percent between 1860 and 1870.

These new freedmen and freedwomen looked to the future as well, organizing schools for themselves and their children and asserting authority over their churches and liturgy. Sometimes freedpeople combined those goals, as did a Black Baptist minister who, having learned to read in slavery, opened a school in Wilkes County.

Most especially, freedpeople refused to work according to old routines. Ideally, they hoped to separate themselves completely from their enslavers by becoming landowners themselves. That independence was nearly achieved by a few, primarily those who settled on the coastal reserve set aside for their exclusive use by Sherman in January 1865 under his Field Order No. 15. Most could not. Slavery had left the majority of Black Georgians bereft of the resources necessary to farm independently, and necessity compelled them to seek employment on white-owned farms and plantations.

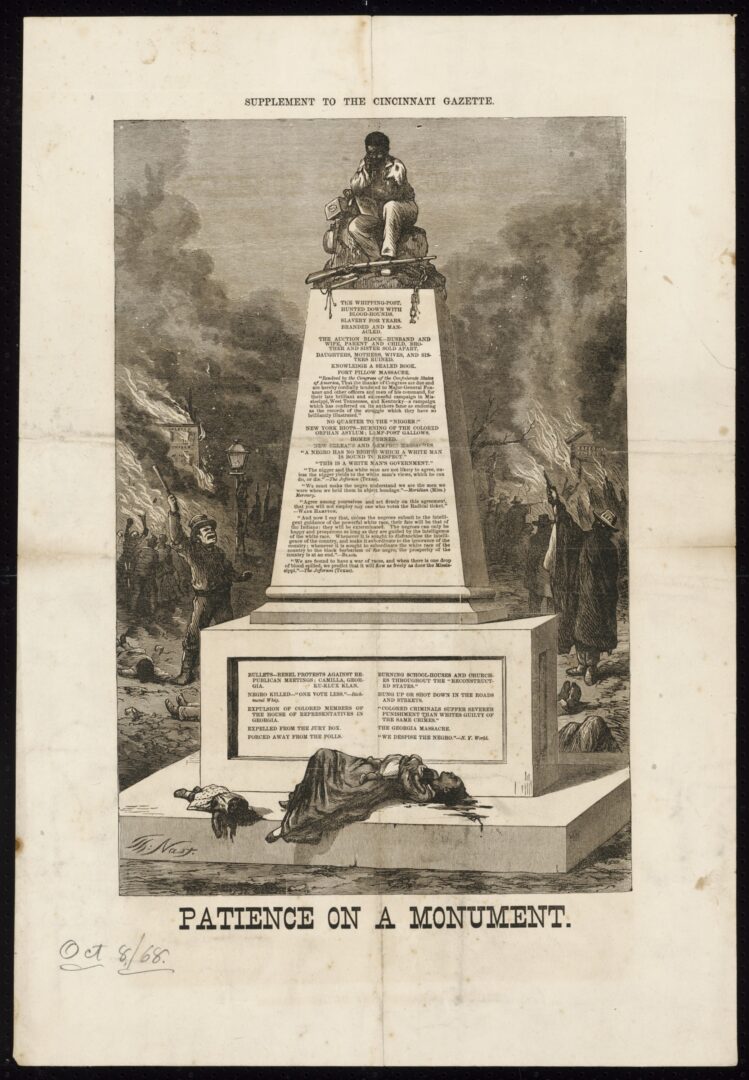

That requirement brought Georgia’s freedpeople into conflict with former slaveholders, who envisioned a very different emancipation. In their minds the best freedom resembled slavery. They preferred that Black people remain in their old homes, accept the same clothing and food provided in slavery, and observe the same rules of etiquette that governed relations before emacipation. Ex-slaveholders saw no reason to foster the education of freedpeople or to permit them to congregate without white supervision. Indeed, for many former owners, such aspirations posed a threat to good order.

Former slave owners especially rejected freedpeople’s desire for economic independence. Dependent on Black labor for their own prosperity, they expected agricultural work to remain unchanged. Black laborers would continue to perform accustomed work in accustomed ways, under the watchful eyes of whip-wielding overseers. Ex-slave owners resisted allowing formerly enslaved people a say in the conditions of work or extending to them the legal and political rights enjoyed by free workers in the North. In the lexicon of the day, liberated African Americans would live and “work as heretofore.”

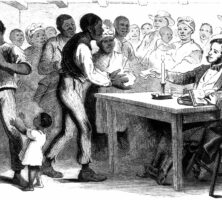

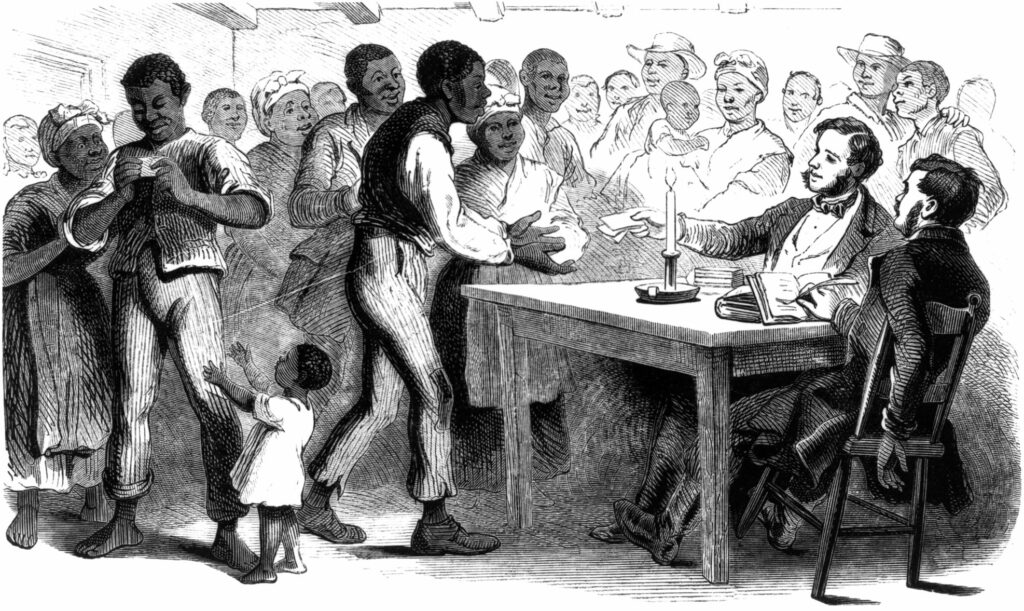

That sentiment did not please the Northerners responsible for enforcing emancipation. Believing that victory on the battlefield had awarded them the right to reshape the South to their own liking, Northern officials such as John Emory Bryant, one of the first Freedmen’s Bureau agents to assume duty in Georgia, anticipated modeling the South after their native society. Formerly enslaved laborers would assume roles as employees, and ex-slaveholders would become employers. Freely and fairly negotiated contracts would compensate industrious workers with material and moral rewards and would ensure landowners of the labor necessary to bring the South back to economic prosperity.

Northerners’ vision left no room for those who yearned for the command of slavery or those who preferred to seek their livelihoods outside wage work. Disputes between employees and employers had to be settled by courts of law, not by recourse to whips. Workers had to be protected in their right to seek out the most favorable and lucrative employment. Promptly paid wages would finance Black people’s pursuit of moral, educational, and economic advancement, especially since the federal officials’ vision of freedom precluded the independence that would have resulted from giving land to formerly enslaved African Americans.

Defining Freedom

Disputes erupted across Georgia as freedpeople, former slaveholders, and Northern victors struggled to enforce their individual visions of freedom. Freedpeople acquiesced to Northern insistence that they return to work, especially since they realized their own well-being depended on seeing the year’s crops to harvest. But they refused to “work as heretofore.” Black Georgians riled ex-slave owners by shortening their work days, demanding payment for services rendered, and exercising their new legal rights to bring charges against employers who attempted to whip them as of old. Most Black parents resisted efforts by Georgia planters to “apprentice” their children to uncompensated farm labor until they reached the age of twenty-one, though some gave in to pressures to do so.

Freedpeople discovered that Northerners were allies in their quest for education and independent churches, whether through government agents, Union troops, or teachers and preachers sponsored by the American Missionary Association and other such organizations. But they also confronted Northerners who seemingly sided with former slaveholders when they impeded Black people’s efforts to seek livings outside wage work or punished those who failed to meet the exact terms of their labor agreements.

No single group achieved its vision of freedom by the end of 1865 and the legal abolition of slavery. But in the struggles of emancipation, Georgians—Black and white—hammered out a compromised freedom. For better or worse, most freedpeople henceforth sought their living through paid labor, usually on white-owned plantations. The conditions of that work and life outside of work reflected Black people’s visions of freedom more than their enslavers’ memories of slavery. Black children and some adults attended schools in Savannah, Augusta, Albany, Atlanta, and elsewhere. Black congregations listened to Black ministers preaching a gospel of their own. Families reunited, often with the assistance of Northern officials. And although white Georgians would continue for some time to monopolize political office, Black Georgians had issued calls for their first convention and had begun planning for the day when they too would exercise the full range of civil and legal rights. Emancipation did not complete the transformation of Georgia society, but it had certainly started that process.