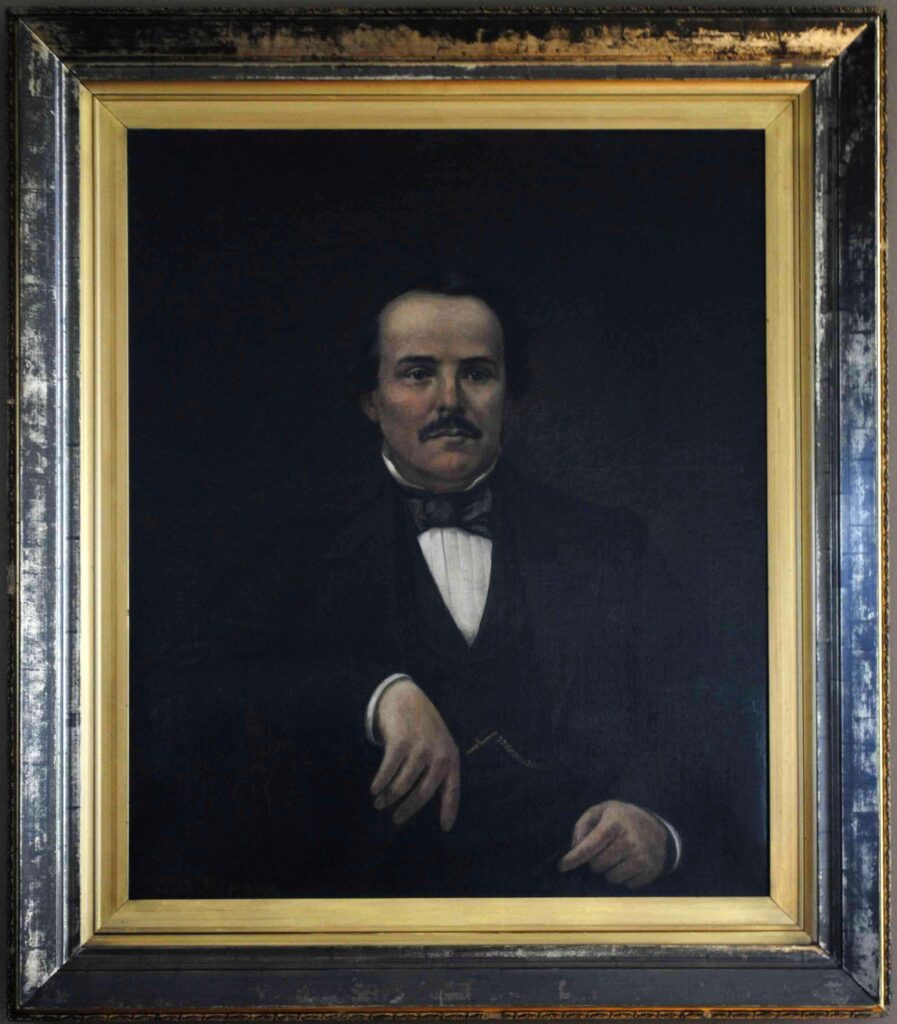

The first high-ranking Georgian to be killed in the Civil War (1861-65), Francis S. Bartow was a leading attorney, politician, and soldier of the mid-nineteenth century.

Courtesy of Georgia Historical Society.

Francis Stebbins Bartow was born on September 6, 1816, in Savannah to Frances Lloyd Stebbins and Theodosius Bartow, who had migrated from New York. After graduating from the University of Georgia, Bartow attended Yale University Law School in New Haven, Connecticut, and then returned to Savannah to read law with John Macpherson Berrien, a U.S. senator and former attorney general of the United States. Bartow began practicing his profession in 1837 and soon became a prominent member of the Georgia bar. He also became one of the largest slaveholders in the state. By 1860 he had accumulated a total of eighty-nine enslaved people, the majority of whom lived and worked at his plantation on the Savannah River in Chatham County.

In 1844 Bartow married Louisa Berrien, the daughter of his mentor, a union that no doubt helped Bartow to launch his own political career. Although a member of the Whig party (like his father-in-law), he also forged close ties with prominent Democrats, including such luminaries as legal authority Thomas R. R. Cobb and his brother, Georgia governor and Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives Howell Cobb. During the 1840s Bartow served two terms in the Georgia House of Representatives, followed by one term in the state senate during the early 1850s. In 1856 he was elected captain of Savannah’s elite Oglethorpe Light Infantry (an association that would have fatal consequences for him), and the next year he made an unsuccessful bid for the U.S. Congress.

In early 1861 Bartow gained further notoriety when, on orders from Georgia governor Joseph E. Brown, he led the Oglethorpe Light Infantry in capturing Fort Pulaski at the mouth of the Savannah River. Shortly thereafter, Bartow was elected a delegate to the state secession convention in Milledgeville, where as a member of the so-called immediate secessionist faction he used his great oratorical skills to influence the convention to pass an ordinance of secession. Following the withdrawal of Georgia from the Union in January 1861, Bartow was elected to the Provisional Confederate Congress in Montgomery, Alabama. There he unsuccessfully schemed with his friends Thomas R. R. Cobb and Howell Cobb to get the latter elected as the new Confederacy’s first president. He also chaired the state house military affairs committee and in this role reputedly selected gray as the color for the Confederate uniforms.

Having campaigned vigorously to create a new nation ruled by slaveholders, Bartow then decided to fight for it. After the Civil War began in April 1861, he rushed home to take the “Oglethorpes” to the front in Virginia. He became embroiled in a confrontation with Governor Brown when he armed his unit with muskets that Brown claimed belonged to Georgia and were intended strictly for state defense, not for troops going into Confederate national service. A heated exchange of letters followed, in which Brown demanded the return of the muskets and Bartow not so politely told him he had no time for such foolishness. At the close of one letter to the governor, Bartow declared, “I go to illustrate, if I can, my native State,” a bombastic yet wonderfully turned phrase that would later adorn his tombstone.

After arriving in Virginia, Bartow was elected colonel of the Eighth Georgia Infantry Regiment. By July 1861 he was in command of a brigade, which he clumsily led into combat at the First Battle of Manassas. On July 21, during a critical moment, he seized the regimental colors and attempted to lead a charge on a Union battery, but he was shot through the heart. He died moments later, supposedly uttering the oft-quoted last words, “They have killed me boys, but never give up the field,” which, along with his earlier quip to Governor Brown, are inscribed on his tombstone.

Bartow’s body was returned to Savannah and buried in the family plot at Laurel Grove Cemetery. The death of the first high-ranking Georgian in the Civil War sent a shock wave through the state and elevated Bartow to a status as a soldier that his ability probably did not merit. As a measure of his fame, several newly raised Confederate military companies and one Georgia town were named for him. The greatest tribute, however, came from the citizens of Cass County, who changed their county name to Bartow in his memory.

One of the enduring myths about Bartow is that by the time of his death he had been promoted to brigadier general. No record of this can be found. Although his leadership of a brigade entitled him to the rank of general (and had he lived he probably would have been promoted to one), nevertheless he died a colonel.