Harrison Berry, a literate enslaved artisan from middle Georgia, was the only Black Georgian known to have written publicly about slavery while still in bondage.

Born in 1816 on the Jones County plantation of David Berry, Harrison received reading instruction from his enslaver’s white children and was, in his own judgment, reared “under auspicious circumstances.” Nonetheless, in many respects his life as an enslaved person was fairly typical: despite his literacy, he worked as a field hand and a craftsman, and he had three different enslavers before emancipation.

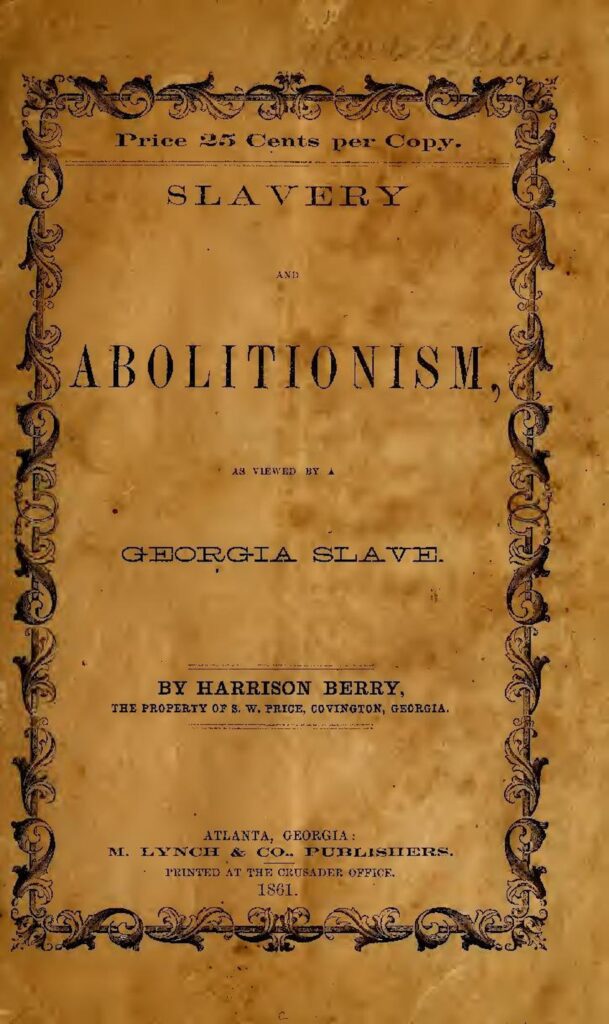

Berry’s principal antebellum publication was a forty-six-page pamphlet entitled Slavery and Abolitionism as Viewed by a Georgia Slave, published in Atlanta in 1861. Written during the wave of anti-Black violence that accompanied the secession crisis, the pamphlet was a nominally proslavery document that urged whites to direct their hostility away from local enslaved people and toward elusive “abolition emissaries” who had come south to incite unrest.

In making his appeal for calm, Berry drew upon the doctrines of the American Colonization Society (ACS), a group of northern whites who promoted Black resettlement in Liberia, Africa, to argue that insurmountable white prejudice rendered emancipation futile unless coupled with plans for Black immigration to Africa. To his enslavers, Berry repeatedly stressed that there was “no such thing as a free Negro in this country.” In Slavery and Abolitionism he was equally blunt: “The colored man is a colored man anywhere. He is but the tool North and the servant South.”

White readers who interpreted Berry’s statements as endorsements of slavery could scarcely have anticipated the character of his postwar writings. In 1866 he submitted an essay “on the equality of the races” to the official journal of the American Colonization Society, only to be rebuffed. The society preferred to “avoid as far as possible going into discussions of this kind,” an ACS official explained, adding, “there stands Liberia, better than a thousand arguments on paper.”

Seeing the disingenuous nature of the colonization movement’s egalitarian rhetoric, Berry embraced the Reconstruction program of Georgia’s Republican Party. His 1869 pamphlet, A Reply to Ariel, was a thirty-six-page tract refuting the white supremacist arguments of the Nashville, Tennessee, fundamentalist Buckner H. Payne, who used the pseudonym “Ariel.” Echoing Republican appeals for a postwar coalition of formerly enslaved people and yeoman whites, Berry wrote that the “diabolical aristocratic slave power” was “perfectly willing to disenfranchise a great number of ignorant whites” together with Black voters in order to keep both groups from voting for free public schools and other reforms. It would then “become a proverb that Negroes were an inferior race and poor whites of low blood.”

Berry lived to see his bleak prophecy at least partially fulfilled. Although his career after 1869 is obscure, he remained in Georgia at least thirteen more years, long enough to witness the reassertion of conservative white dominance over many aspects of Black life. His last known publication, entitled The Foundation of Atheism Examined, with an Answer to the Question “Why Don’t God Kill the Devil?” (1882), suggests that he may have become a minister by the 1880s. The place and date of his death are unknown.