The Inman family is representative of those members of the planter class who lost much of their wealth during the Civil War (1861-65) but recouped their fortunes in a postwar urban environment. They contradict C. Vann Woodward’s theory that the New South was run by new men, meaning nonplantation elites. Instead, the Inmans better fit the theory of those historians who argue that members of the planter class evolved into the South’s political and economic leaders, roles which were not new to them, after the Civil War.

The Inmans came to Atlanta from eastern Tennessee around the time of the Civil War. In 1865 Shadrach W. Inman followed his two younger brothers, William H. Inman and Walker P. Inman, who had arrived in 1859 and were acting as agents for the Northwestern Bank of Georgia in Ringgold. Shadrach established dry-goods stores with his youngest son, Hugh, in Atlanta. Meanwhile, William, along with Shadrach’s second son, John, went to New York to act as the family’s connection there. Samuel, Shadrach’s eldest son and the grandfather of Atlanta poet and diarist Arthur Crew Inman, went to Augusta and worked in a dry-goods store there with his future brother-in-law, Samuel K. Dick.

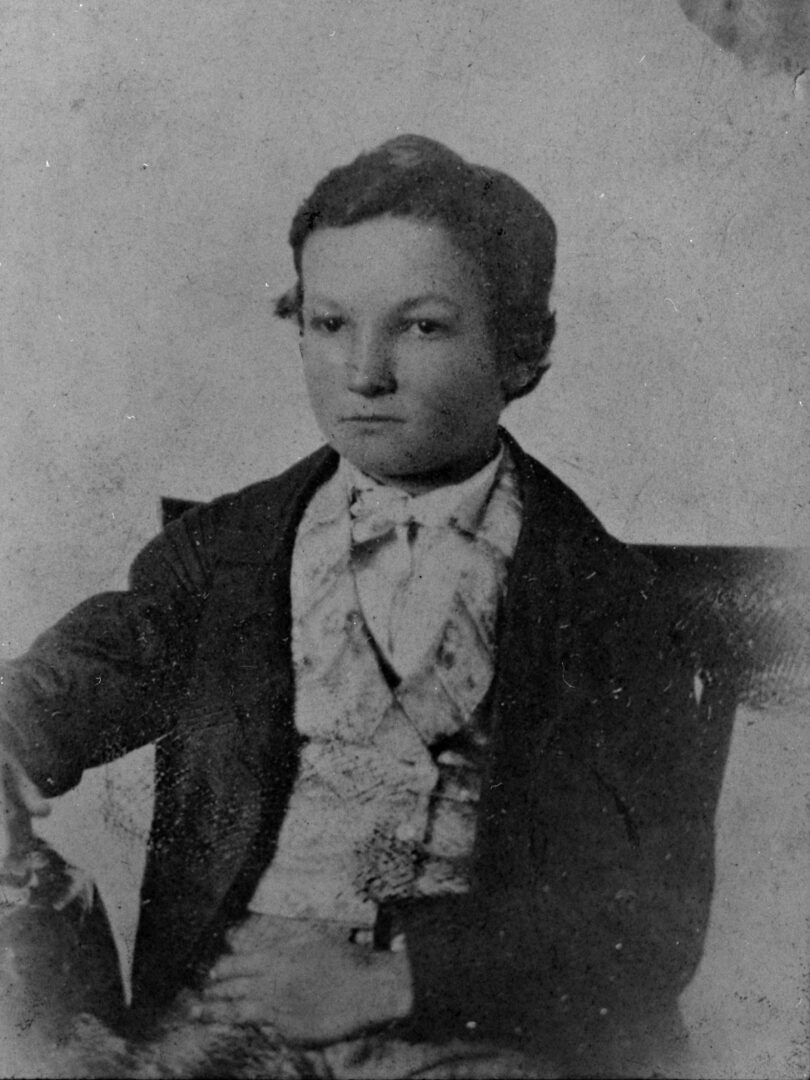

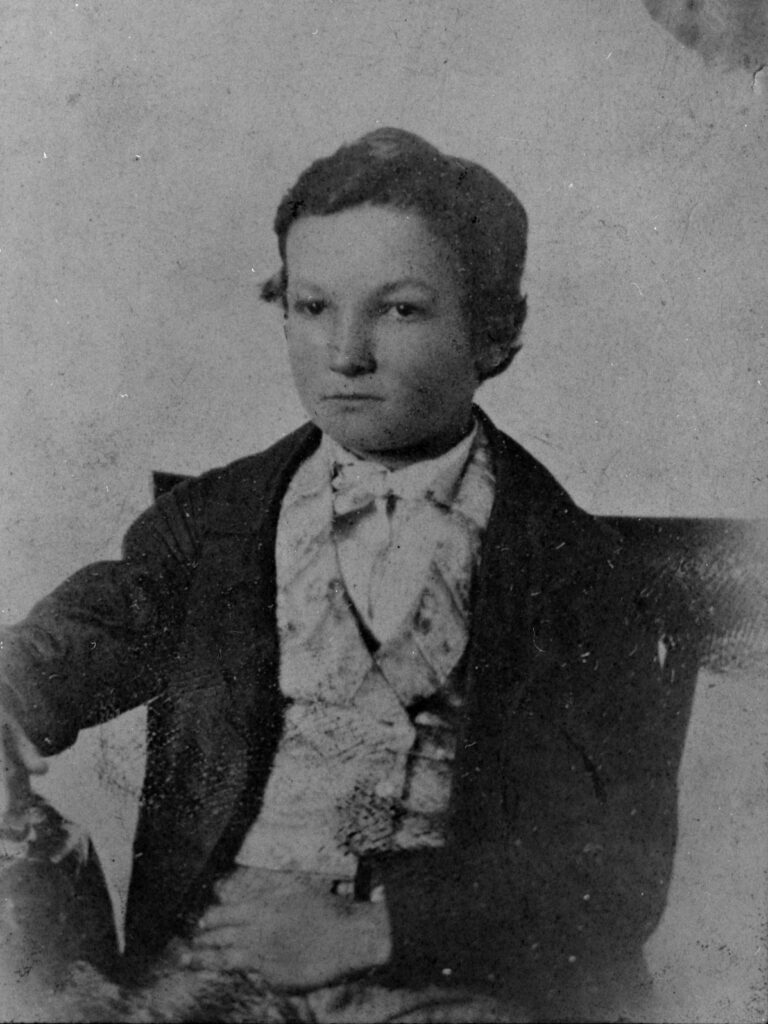

Courtesy of Atlanta History Center.

The dry-goods stores of the time served as places to barter goods, particularly for farmers growing cotton, but were later discontinued in favor of direct dealings in cotton. The Inmans worked as factors, purchasing cotton from farmers and reselling it when the market turned more favorable. From their interest in cotton they expanded into such related areas as fertilizers, cotton presses, steel hoops to hold compressed cotton, and railroads for the shipping of cotton.

In order to influence shipping rates, the Inmans obtained positions on the boards of various railroads and as voting stockholders. As a result of serving in these capacities, John H. Inman became president of the Richmond and Danville Railroad in 1890. As president, Inman was accused of charging the Richmond and Danville too much money for the stock of the Central of Georgia Railway, of which he was one of the largest stockholders. Due to this conflict of interest, Inman was forced to resign in 1892, and investigations followed. He never recovered from this incident and died on November 5, 1896, with his once wealthy estate in bankruptcy.

Samuel and Hugh, on the other hand, found their interest in various businesses growing along with the city of Atlanta. Starting as railroad stockholders, they became investors in streetcars with their friend Joel Hurt and began to invest in banks, often serving as board members of those banks. Atlanta real estate also became a large part of the Inmans’ business interest, as did insurance, which, because of the threat of fire to their real estate investments, was a natural progression.

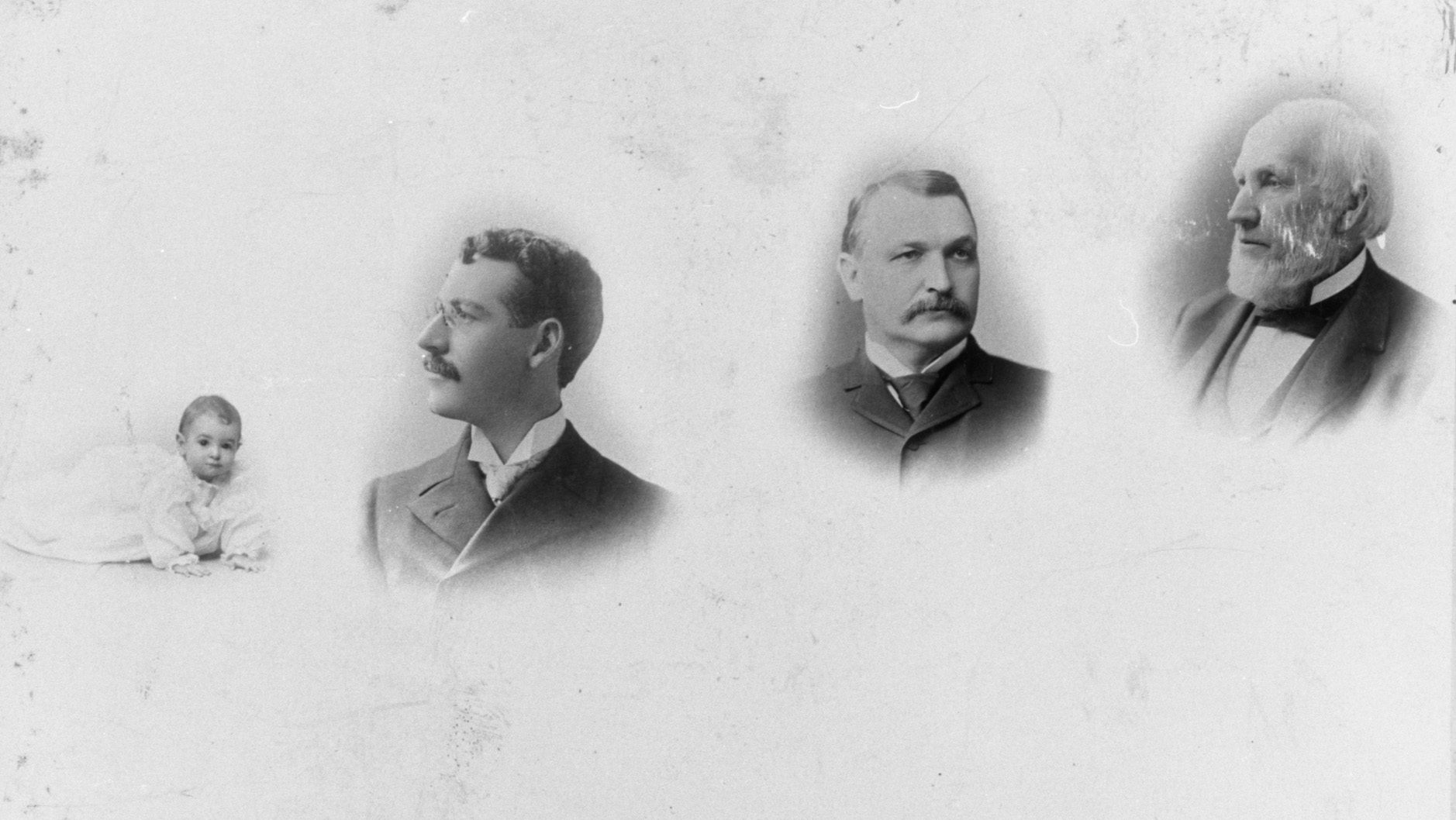

Courtesy of Atlanta History Center.

The Inmans were soon able to venture beyond the world of business and into the politics of the city. Samuel and Hugh served as aldermen and as members of various civic organizations, all the while pushing the physical development of Atlanta and improving the value of their real estate investments. As civic leaders they were also involved with city boosterism in the form of expositions, including the Cotton States and International Exposition of 1895.

Through the money they made on cotton and railroads, the Inmans were able to participate in philanthropic activities in Atlanta. They were key to the development of the Georgia Institute of Technology and Agnes Scott College, as well as, to a lesser extent, Atlanta University and Oglethorpe University. Other charities supported by the family included churches, the Confederate Soldiers’ Home, and Women’s Work in the American Red Cross during World War I (1917-18). The Inmans also supported the founding of an orphanage and of Grady Memorial Hospital. Many cultural endeavors, including the High Museum of Art, also benefited from the Inmans’ generosity.

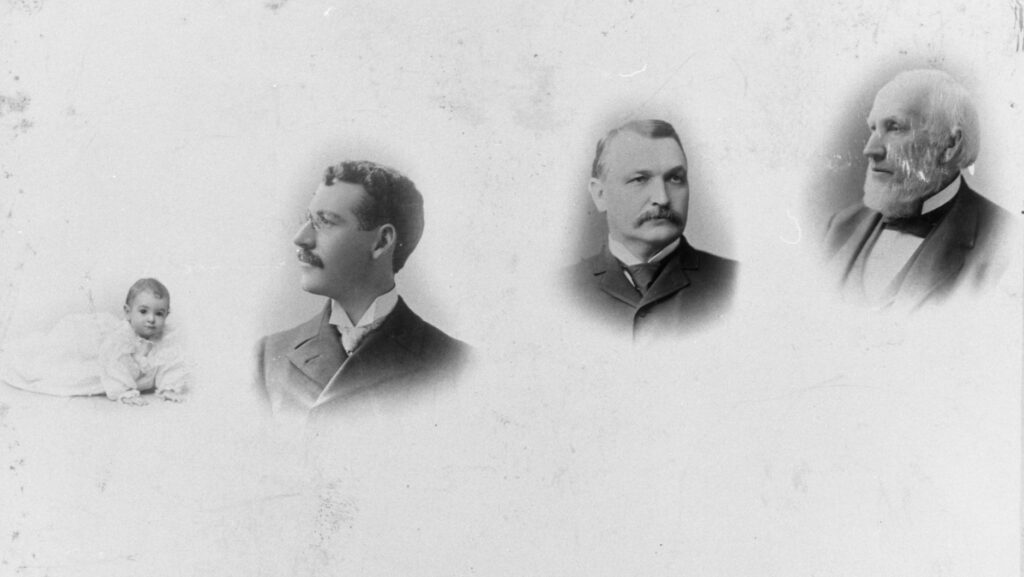

Courtesy of Atlanta History Center.