John Zubly, a Calvinist minister, was the first pastor of the Independent Presbyterian Church in Savannah. A religious leader known throughout the colonies, the Reverend John Zubly was a revolutionary pamphleteer whose broadsides supporting the colonies in their disputes with Britain were widely distributed on both sides of the Atlantic. He was a representative from Georgia to the Second Continental Congress. Notwithstanding his fame and importance during the years of 1750 through 1775, he has been all but forgotten because he became a Loyalist when he found himself unable to support the war for independence from Britain.

John Joachim Zubly was born Hans Joachim Zublin, in St. Gall, Switzerland, on August 27, 1724. His father, David Zublin, was a weaver who immigrated to South Carolina in 1736 while Zubly remained in St. Gall to continue his education. Zubly was ordained in the German Reformed Church in London in 1744. He arrived in South Carolina soon after his ordination and within a year was preaching in the Georgia communities of Vernonburg and Acton. These communities, located south of Savannah, were settled by German and Swiss immigrants and had been trying to arrange an appointment of Zubly as their pastor since 1742. In 1746 Zubly married Anna Tobler, the daughter of the publisher John Tobler. They had three children, John, Anne, and David. After Anna died in 1765, Zubly married Anne Pyne.

In 1748 Zubly accepted a position as pastor to the Wappetaw Independent Congregational Church in Wappetaw, South Carolina. He held this position until 1759. In 1760 he accepted a position as the first pastor of the Independent Presbyterian Church of Savannah, where he remained until his death in 1781.

The Philosophical Preacher

Zubly was known as a man of “lively cheerfulness” whose sermons were described as being “full, clear, concise, searching, and comfortable,” lighting the hearers’ souls, warming their hearts, and raising their affections. Zubly was known to preach in the morning in English, in the afternoon in French, and in the evening in German. His strict Calvinist theology was very suitable to life in the multicultural environment of the American colonies in the eighteenth century.

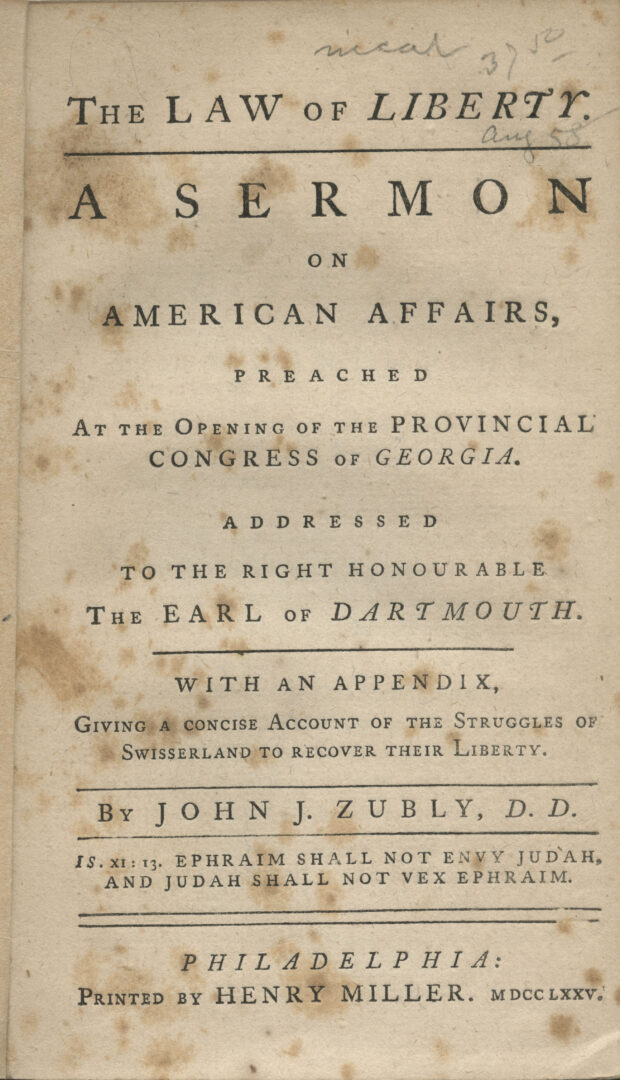

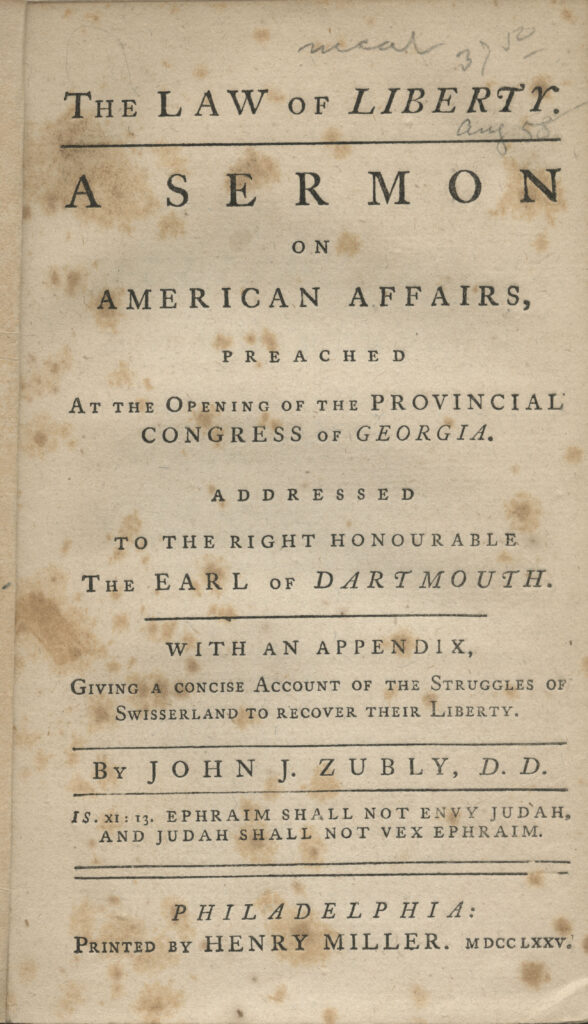

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

Zubly was the author of several theological works that were written in German, English, and Latin. He earned his master of arts degree in 1770 and doctor of divinity degree in 1774 from the College of New Jersey (later Princeton University). His personal library of more than 2,000 volumes, one of the largest in the colonies, reflected the breadth of his knowledge and interests. One of his most important surviving theological works is The Nature of That Faith (1772).

The Revolutionary Pamphleteer

Zubly was quick to take up the pen to defend the colonies in their conflicts with Britain or to expose the attempts of the official Anglican Church to tyrannize those who held different religious views. Beginning in 1766 with the Stamp Act crisis, Zubly wrote a series of pamphlets on the various controversies between the colonialists and the British authorities. His most widely circulated work was written at the request of the 1775 Provincial Congress of Georgia. In this work Zubly addressed the King’s representative in the American colonies, the earl of Dartmouth. In passionate language rivaling that of Thomas Jefferson’s draft of the Declaration of Independence in its defense of the colonies, Zubly described the nature of the atrocities committed by the British against the Americans and warned of the consequences. This work was reprinted in London Magazine in January 1776 as an articulate explanation of the case for the colonies.

In 1772 a supporter of British policies referred to Zubly’s writings as “mere Sophistry, and a jingle of words without meaning.” Historians have, however, recognized the importance of Zubly’s work as a revolutionary pamphleteer in helping eighteenth-century Americans work through issues involving governments based on constitutions and liberty. In July 1775 Zubly was elected by the citizens of Georgia as one of their representatives to the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia.

The Loyalist

From the first day of his term in the Continental Congress, Zubly opposed independence. At the Congress, he joined with other delegates in opposing a strict adherence to the embargo on British goods. His most intense debates on the issue of the embargo were with Samuel Chase of Maryland. Those frequent floor fights between Zubly and Chase were so intense that a year later delegates found occasion to recall them.

On November 10, 1775, Zubly left Philadelphia and returned to Georgia. He was branded a traitor because of his opposition to independence. On July 1, 1776, the Council of Safety of Georgia ordered his arrest. He was banished from Georgia, and half of his property was confiscated. A crowd of patriots stormed his home and threw his library into the Savannah River. He took refuge with Loyalists in South Carolina, but returned to Savannah when the British retook the town in 1778.

Zubly’s pen, however, was not silenced. In 1780 and 1781 Zubly wrote a series of nine essays under the pseudonym of Helvetius. These essays were published in The Royal Georgia Gazette and in John Tobler’s The South-Carolina and Georgia Almanack for the Year of Our Lord 1781. In these essays Zubly used international law and the Bible to show that Americans were not fighting a legal revolution but were engaged in an illegal and unjust rebellion of which God disapproved.

Zubly’s last Helvetius essay, printed in The Royal Georgia Gazette of May 24, 1781, compared the rebelling colonies’ prospects and conditions in 1776 with those of 1781. In May 1781 the Americans’ prospects and conditions were not good, as Zubly was quick to point out. The war for independence was at the time not favoring the Americans. However, Zubly would never witness the dramatic turn in the fortunes of the Americans and their eventual victory at Yorktown, Virginia, in October 1781. On July 23, 1781, he died, peacefully, surrounded by family and friends and confident that history had proved he was justified in the rightness of his opposition to the war for independence.