John Ross became principal chief of the Cherokee Nation in 1827, following the establishment of a government modeled on that of the United States. He presided over the nation during the apex of its development in the Southeast, the tragic Trail of Tears, and the subsequent rebuilding of the nation in Indian Territory, in present-day Oklahoma.

Ross was born on October 3, 1790, in Turkey Town, on the Coosa River near present-day Center, Alabama. His family moved to the base of Lookout Mountain, an area that became Rossville, Georgia. At his father’s store Ross learned the customs of traditional Cherokees, although at home his mixed-blood family practiced European traditions and spoke English.

After attending South West Point Academy in Tennessee, Ross married Quatie (also known as Elizabeth Brown Henley). He began selling goods to the U.S. government in 1813. The profits from the store at Ross’s Landing on the Tennessee River (at present-day Chattanooga, Tennessee) enabled Ross in 1827 to establish a plantation and ferry business where the Oostanaula and Etowah rivers flow together to form the Coosa River, located at what is now Rome.

During this period Ross’s diplomatic skills enabled him to achieve prominent positions, culminating in his election as principal chief of the newly formed Cherokee Nation, which Ross, along with his friend and neighbor Major Ridge, helped to establish. As Ross took the reins of the Cherokee government in 1827, white Georgians increased their lobbying efforts to remove the Cherokees from the Southeast. The discovery of gold on Cherokee land fueled their desire to possess the area, which was dotted with lucrative businesses and prosperous plantations like Ross’s. The Indian Removal Bill passed by Congress in 1830 provided legal authority to begin the removal process. Ross’s fight against the 1832 Georgia lottery, designed to give away Cherokee lands, was the first of many political battles.

Ross’s faith in the republican form of government, the authority of the U.S. Supreme Court, and the political power of Cherokee supporters, especially the Whig Party, gave him confidence that Cherokee rights would be protected. When the fraudulent Treaty of New Echota was authorized by one vote in the U.S. Senate in 1836, Ross continued to believe that Americans would not oust the most “civilized” native people in the Southeast. He fought removal until 1838, when it was clear there was no alternative; he then successfully negotiated with the U.S. government to handle the business of the move.

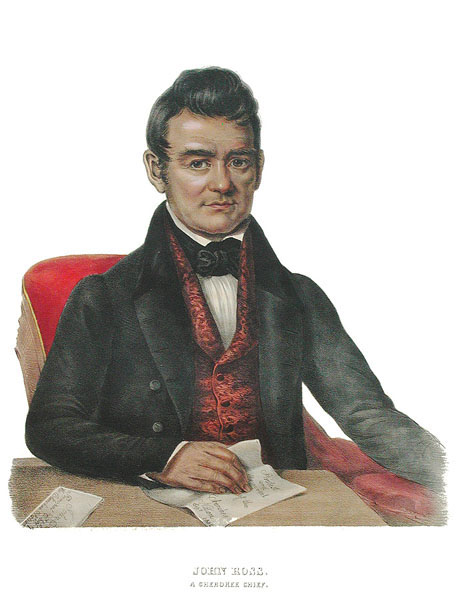

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

Ross supervised the removal process from Tennessee until December 1838. Ross, Quatie, and their children then joined the last detachment of departing Cherokees, who were traveling by boat because they were too old or sick to travel overland. Ross, too, experienced personal tragedy along the “trail where they cried,” or the Trail of Tears, as Quatie died during the journey in early 1839.

Once in Indian Territory, Ross led the effort to establish farms, businesses, schools, and even colleges. Although the Cherokee Nation was torn apart politically after the fight over the removal treaty, Ross clung to the reins of power. When the Civil War (1861-65) began, Ross initially sided with the Confederacy but soon switched to the Union position. Once again, the Cherokee nation split. Pro-Confederates elected Stand Watie as chief in 1862, while pro-Union supporters reelected Ross. The United States continued to recognize Ross’s government. He remained principal chief of the Cherokee Nation until his death in Washington, D.C., on August 1, 1866.