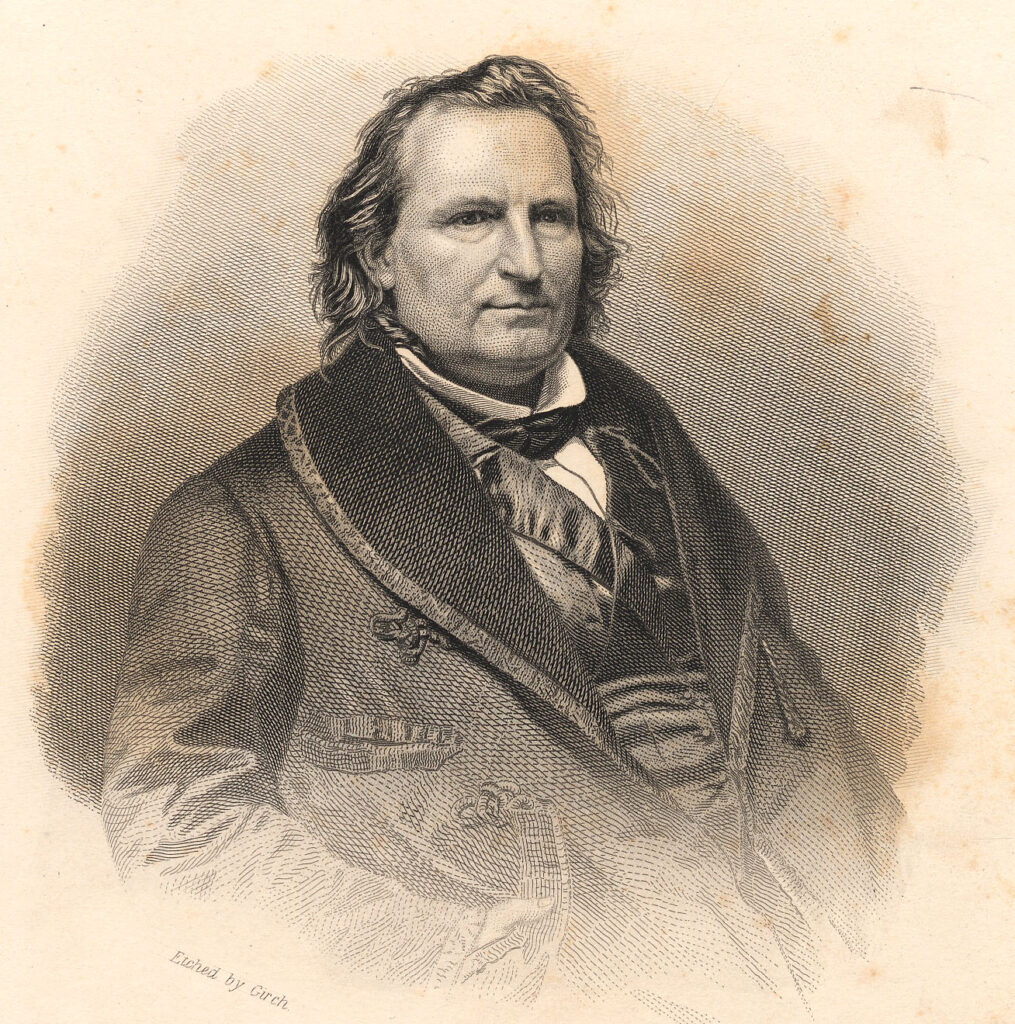

Joseph Henry Lumpkin served on the Supreme Court of Georgia from 1846 until his death in 1867. One of three justices elected by the Georgia legislature after the supreme court’s creation in 1845, Lumpkin was elected to successive terms without opposition. He was considered the chief justice of the court until officially named to that position by the legislature. An active supporter of education, he cofounded the University of Georgia law school, which now bears his name.

Born in Oglethorpe County, on Georgia’s frontier, Lumpkin grew up in a religious and politically active family. His brother Wilson Lumpkin served not only as governor of Georgia but also as a United States representative and senator. Joseph Lumpkin, however, served just two terms in the Georgia legislature for Oglethorpe County (1824-25), deciding to devote his full attention to his law practice.

As a lawyer Lumpkin gained a great reputation for his trial skills and oratory. He also advocated reformation of Georgia’s legal system through a reorganization and simplification of the state’s laws. In 1833 he served on a commission that created Georgia’s first penal code, which replaced a confusing array of outdated and disorganized criminal laws. After his appointment as a Georgia supreme court justice, he pushed for the streamlining of judicial procedures to increase the efficiency of the court system and make it more accessible to the public. Lumpkin was known for the quality of his legal opinions and judicial reasoning. He was best known, however, for the militant proslavery views that often appeared in his opinions in suits involving enslaved people. In 1855 Lumpkin declined U.S. president Franklin Pierce’s offer of a seat on the newly created federal court of claims, preferring to remain on the Georgia bench.

Although Lumpkin eschewed politics in favor of the law, he remained interested in state and national politics. A vigorous proponent of states’ rights, he nevertheless joined the Whig Party and supported many of that party’s national policies calling for internal improvements. He remained a Whig until that party collapsed in the 1850s. Lumpkin believed that a state had the power to leave the Union if the federal government overstepped and abused its authority. He was not, however, an early advocate of secession in the decades leading up to the Civil War (1861-65) but did support secession after the election of Abraham Lincoln to the presidency in 1860.

Religion played an important role in Lumpkin’s life. In the early 1820s Lumpkin underwent an evangelical conversion that profoundly affected his life. He took an active part in the temperance movement on both the national and state levels. He also believed that slavery was sanctioned by the Bible and often cited religious arguments to support continuation of that institution.

In addition to his temperance activities, Lumpkin sought to strengthen southern society through the expansion of education and industry. He worried that the lack of an educated general population and reliance on northern colleges for higher education endangered the South’s ability to maintain its social and political institutions, such as slavery, against outside interference. For this reason he actively supported schools and colleges, serving as a trustee of the University of Georgia and teaching in the law school he helped to found. Lumpkin also advocated development of a southern manufacturing base, beginning with textiles, to eliminate southern dependence on northern and European manufacturers for finished goods and markets for southern raw materials. Additionally, industrialization would provide employment for poor whites who might otherwise pose a threat to the stability of the region.