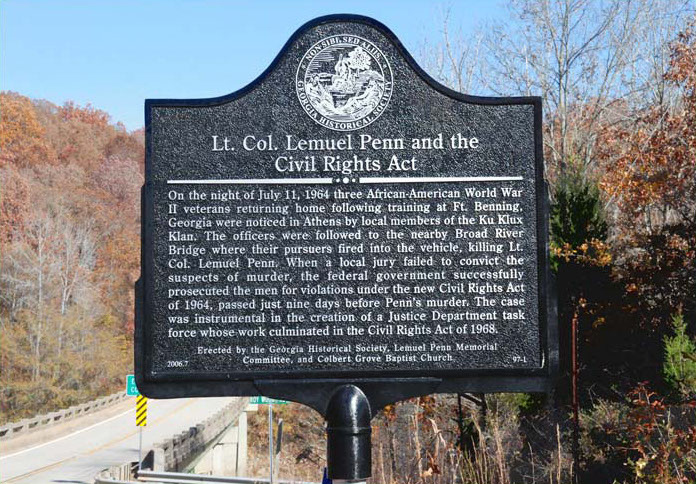

In July 1964 Athens-area Ku Klux Klan members shot and killed Lemuel Penn, an African American World War II (1941-45) veteran and officer in the U.S. Army Reserves, who was returning home to Washington, D.C., after reserve training at Fort Benning (later renamed Fort Moore). Penn’s murder captured headlines nationwide, dramatizing the need for civil rights reform and ultimately prompting a reappraisal of Klan activity throughout the South.

The Murder

In the early hours of July 11, 1964, a Chevrolet sedan carrying U.S. Army Reserve officers Charles E. Brown, John D. Howard, and Lemuel Penn departed Fort Benning outside Columbus and headed north for Washington, D.C. After two weeks of active army reserve training, the men were returning home to resume their civilian routines as educators in the District of Columbia school system. They stopped briefly in Athens, where Penn relieved Brown at the wheel before steering the vehicle northward down Georgia Highway 72.

According to subsequent reports, neither Penn nor his passengers noticed the Chevy II station wagon that followed the men out of town. The pursuing vehicle was trailing the officers from a distance when they turned onto 172 outside Colbert, in Madison County, but pulled alongside their sedan as it crossed the Broad River Bridge near the Madison-Elbert County line. Two shots were then fired from inside the station wagon, and Penn was killed instantly.

The Trial

News of Penn’s murder traveled fast throughout the state and nation. Aghast at the tide of extralegal violence then sweeping across the region, Georgia governor Carl Sanders declared that he was “ashamed for myself and the responsible citizens of Georgia that this occurrence took place in our state.” No less concerned was U.S. president Lyndon B. Johnson, who pledged the full resources of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) toward solving the murder. Over the course of the next several weeks, FBI agents combed for clues in and around Athens, gathering ample evidence of criminal activity conducted by local Klan members. After weeks of investigation, state prosecutors brought first-degree murder charges against two local white men, Cecil Myers and Joseph Howard Sims. Despite considerable evidence indicating their guilt, an all-white jury in Madison County acquitted both men on September 4, 1964.

The defendants’ acquittal may not have been surprising. For generations, white jurors across the region had routinely excused acts of violence visited on African Americans. The racial injustice that pervaded southern courtrooms only intensified during the civil rights era as numerous perpetrators of crimes against Black activists escaped justice. Unlike most of the movement’s martyrs, however, Penn had steadfastly avoided racial conflict. According to friends, Penn was a committed father and husband who preferred volunteerism to marching for racial equality. As his wife later testified, Penn had never joined a civil rights organization and had stayed on base during his entire two-week stint at Fort Benning in order to avoid “racial unpleasantness.”

Federal authorities remained committed to bringing Penn’s murderers to justice. FBI agents had uncovered numerous acts of intimidation and brutality during the course of their investigation, enough evidence, they believed, to secure a guilty verdict in a federal court. On the basis of the 1870 Enforcement Act (better known as the First Ku Klux Klan Act) and the recently enacted Civil Rights Act of 1964, federal authorities charged Sims, Myers, and four other Klansmen, Herbert Guest, James S. Lackey, Denver Phillips, and George Hampton Turner, with conspiring to abridge or threaten another person’s civil rights.

Although federal district judge William Bootle approved an appeal alleging that federal authorities were usurping state jurisdiction, the U.S. Supreme Court later reversed the ruling, affirming the federal government’s right to bring suit. Criminal proceedings against the men began on June 27, 1966, two years after Penn’s murder, and rulings were read separately two weeks later. Though four of the defendants were found innocent, Sims and Myers were both convicted on conspiracy charges and sentenced to ten years apiece in the federal penitentiary.

As veteran journalist Bill Shipp recounts in his book Murder at Broad River Bridge: The Slaying of Lemuel Penn by Members of the Ku Klux Klan (1981), the Klan entered a period of steep decline during the late 1960s. Due in large part to Penn’s murder and similar acts of violence, the House Committee on Un-American Activities launched a full-scale investigation into the Klan’s activities in 1965, exposing the organization’s penchant for violence and utter disregard for the law. Membership declined thereafter, and the organization never regained the prominence and legitimacy it had previously enjoyed in some communities throughout the South.