Nathanael (sometimes spelled “Nathaniel”) Greene was one of the most respected generals of the Revolutionary War (1775-83) and a talented military strategist. As commander of the Southern Department of the Continental army, he led a brilliant campaign that ended the British occupation of the South. Although Greene never fought a battle in Georgia, his leadership was the catalyst that turned the tide toward American victory in the colony, freeing Georgia from British forces. Greene County in northeast Georgia is named in his honor.

Early Life

Greene was born in 1742 and reared in Rhode Island, the son of Nathanael Greene, a businessman and a minister of the Society of Friends (Quakers), and his father’s second wife, Mary Mott. He was brought up in the Quaker church, a faith that denounces warfare. Greene lived a quiet life as a blacksmith in his father’s iron foundry before the war. An avid reader, he developed an early interest in military science, upsetting both his family and the Quaker community.

Greene was elected to the Rhode Island legislature in 1770 and became an eager advocate for American independence from Britain. After attending a military parade in 1773, he was expelled from a Quaker meeting. From then on, Greene chose to separate himself from the faith and became actively involved in military service.

In 1774 Greene married a fellow Rhode Islander, Catharine Littlefield, with whom he had six children. Catharine visited her husband often during the war and gained a reputation as an independent woman unusually interested in politics and the military.

Military Career

In 1774 Greene helped form the Kentish Guards, a Rhode Island militia unit. He was only allowed to serve as a private in the group, however, because of a slight limp that he had had since birth. Greene later commanded the Rhode Island militia and became a brigadier general in the Continental army, acting in the siege of Boston in 1776. His performance impressed General George Washington, who gave Greene the command of Boston after the British evacuated the city. At the age of thirty-four Greene was promoted to become the youngest major general in the Continental army up to that time. (Four months later, the Marquis de Lafayette became a major general at the age of nineteen.) He participated in the Battles of Trenton in New Jersey and Brandywine and Germantown in Pennsylvania, and acted as quartermaster general at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania.

The Southern Campaign

In 1780 Washington gave Greene the arduous task of leading the feeble Revolutionary army of the South. The army had already had three commanders, whose failures had left the South in a weak and uncertain state. Greene and his men would face the most able of the British generals, Lieutenant General Charles Earl Cornwallis. His large and well-trained army was a daunting challenge to Greene’s small, inexperienced, and poorly supplied Continental forces.

Greene led a bold and ingenious fight against British occupation in the South. While he knew that his army was not capable of winning any large or decisive battles, Greene used the small size of his forces to make sudden, brief attacks on the conspicuous and slow-moving British army. He also daringly divided and thus weakened his army, forcing Cornwallis to do the same. Greene knew that such a move would have grave consequences for the British, greatly reducing their strength. He then led his men in a retreat that forced Cornwallis to follow the Continental army far away from the British supply base in Charleston, South Carolina. Through tactics such as these the British army became a less formidable force.

Greene and the Revolution in Georgia

Although Greene himself never fought in Georgia, he was aware of the grave situation there. By 1780 the British had secured almost all of Georgia, and the remains of its government had dissolved under royalist rule. Greene took a personal interest in saving the vulnerable colony, sending his best generals for its protection and closely overseeing the colony’s affairs.

Image from sfgamchick

In May 1781 patriots led by Elijah Clarke and Andrew Pickens fought to regain control of Augusta, a crucial town in the struggle for Georgia. Greene sent an army under Colonel Henry “Light-Horse Harry” Lee to support the revolutionaries. As the first troops of the Continental army to enter Georgia in more than a year, they boosted the morale of the Georgia residents. With their help, Augusta was back under American control within two weeks.

In 1782 Greene came to the defense of Georgia once again when he sent General “Mad” Anthony Wayne to Savannah. Greene directed Wayne’s successful campaign, which pushed the British out of Savannah and into Charleston, thus ending British occupation of Georgia.

Greene not only fought to secure the freedom of Georgia but also worked with the state to revive its government. He had gained the respect and trust of its residents during the war, and they were eager to have his help in reorganizing their government. Greene encouraged the creation of an official Georgia Brigade, giving the state a symbol that its residents could look to with pride and patriotism. He also oversaw the organization of a new constitutional government and worked closely with the leaders of Georgia. Greene advocated the end of violence against British Loyalists, called Tories, in favor of peace and stability rather than revenge. With his help Georgia reinstated a secure civil government worthy of its independence.

After the War

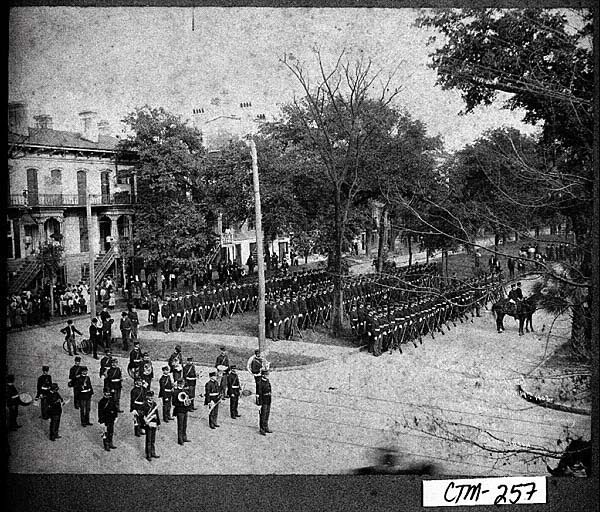

Greene willingly gave much of his personal wealth to help support the war, even sacrificing his Rhode Island home. To thank him for his service during the war, the Georgia government gave Greene a plantation named Mulberry Grove, outside Savannah in Chatham County. He lived on the Mulberry Grove estate for less than a year, troubled by insecure finances; the plantation did not become profitable. Greene died unexpectedly of sunstroke in 1786, at the age of forty-four. Initially buried in Savannah’s Colonial Park Cemetery, Greene was reinterred in 1902 beneath the monument erected in his honor at Johnson Square. The remains of his son, George Washington Greene, are buried there as well.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

After Greene’s death, a young Yale University graduate, Eli Whitney, came to Savannah to take a tutoring job. Whitney began working for Greene’s widow, Catharine, and it was at Mulberry Grove that Whitney invented the cotton gin, the machine that revolutionized the production of cotton.