Once Georgia’s third largest town, Petersburg, located in the forks of the Broad and Savannah rivers in Elbert County, is now submerged under the waters of Clarks Hill Lake. During prolonged droughts, or when lake levels are down, it is possible to walk along the site and see the remnants of what was, from the 1780s to the 1820s, a thriving frontier community.

From Old Petersburg and the Broad River Valley of Georgia, by E. M. Coulter

Early History of Site

Before the founding of Petersburg, the naturalist William Bartram traveled through the area and left his account of Fort James, a small British outpost located on the town’s future site and named after Georgia’s colonial governor, James Wright. According to Bartram, the square fort was manned by fifty rangers and covered an acre of ground along a plateau overlooking the forks of the two rivers. Just above the forks was a series of Indian mounds that Bartram described in detail. Like Petersburg, these mounds no longer exist and the site is underwater. Wright’s plans to construct a town named Dartmouth on the site of the fort were frustrated by the coming of the American Revolution (1775-83).

After the American Revolution, many white settlers, especially from Virginia and North Carolina, came to the region. Of particular relevance were several families of Virginians, led by George Mathews, who settled along the Broad River valley and established a frontier community known as Goose Pond. Among the Virginia transplants was Dionysius Oliver, a Revolutionary War veteran who acquired several land grants from the state for his wartime participation. One of the grants included the land between the forks of the Savannah and Broad rivers. In 1786 Oliver petitioned the state for permission to set up a tobacco inspection warehouse on his property. The state promptly agreed to Oliver’s request. Most of the citizens in the Broad River valley were planting tobacco at the time, and there was a dire need for warehouses in the region to inspect the crops.

Years of Growth

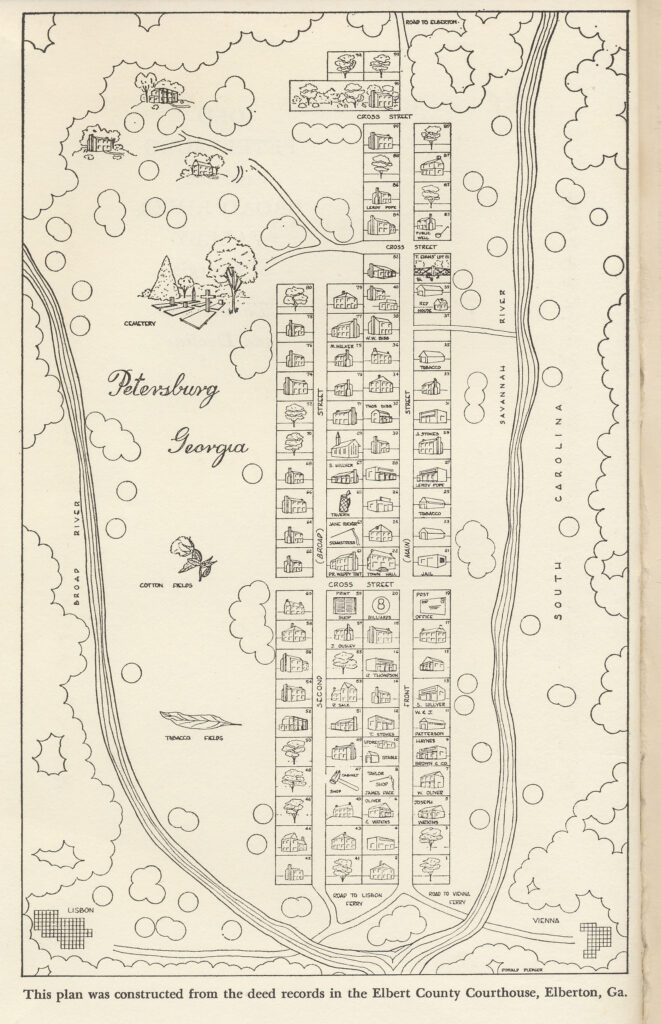

The idea of a tobacco warehouse blossomed into a plan to construct an entire town on the small peninsula. Named for the place of Oliver’s birth in Virginia, Petersburg was divided into eighty-six lots of one-half acre each, and Oliver was immediately besieged with buyers. Speculation drove lot prices to high levels, and the town’s population began to swell. By 1800 it was estimated that Petersburg had a population of approximately 750 permanent inhabitants. The time of its greatest prosperity was from the 1790s until about 1810. During its boom years, Petersburg attained many facilities essential to a town of its stature, including a post office, which began service in 1795; a newspaper (the Georgia and Carolina Gazette), which began publication in 1805; several mercantile firms and businesses; a number of taverns; a town hall; and a jail. In addition to a number of residences, Petersburg also boasted a cabinet shop, a tailor shop, a seamstress shop, horse stables, a church, a few schools, and tobacco warehouses.

Photograph by Darby Carl Sanders, New Georgia Encyclopedia

There was plenty of social entertainment in Petersburg, including plays, balls, promenades, picnics, and community celebrations. The upper class was well represented in the town, and among its residents were doctors, lawyers, and politicians. Petersburg also has the distinguished honor of being the only town in the nation’s history to produce two U.S. senators, William Bibb and Charles Tait, who served at the same time. Petersburg and the Broad River valley also loomed as a crucial arena for the development of political alignments in Georgia’s history during the early national period, especially between factions claiming Virginian ancestry and those linked to North Carolina families.

An important factor in the growth and development of Petersburg was the existence of two rival towns—Lisbon, founded by Virginian Zachariah Lamar in 1786, just across the Broad River in Lincoln County, and Vienna, founded about 1795, on the opposite side of the Savannah River in South Carolina. Both Lisbon and Vienna were clearly visible from Petersburg. Although Lisbon and Vienna competed with Petersburg for trade, neither town rose to a position of economic dominance. There was, however, a constant ferry service that ran between all three towns.

As long as tobacco remained an important staple crop in the Broad River valley, Petersburg flourished. Tobacco was packed into wooden casks, known as hogsheads, for shipment down the Savannah and Broad rivers on flat-bottomed “Petersburg boats” designed to carry ten to fifteen hogsheads of tobacco. The boats were propelled along by river currents and poles manned by a crew of five or six hands. After tobacco crops were inspected in Petersburg or Lisbon, the Petersburg boats made their way to Augusta, about sixty miles downriver, to deliver their cargo. Often the trip to Augusta and back took about a week to accomplish.

Demise of Community

Signs of Petersburg’s demise were increasingly evident by the 1820s. Lot number eighty-one, for example, sold for $2,500 in 1818. However, the same lot sold in 1826 for only $275. By 1830 the town was fast falling into decay. Many of the original families caught western fever, abandoned the region, and moved to the newly opened lands in western Georgia and in Alabama and Mississippi. Periodic outbreaks of yellow fever in the Broad and Savannah river settlements during the 1820s hastened the town’s decline. Many of the area’s farmers had abandoned the production of tobacco by the turn of the nineteenth century and turned their attention instead toward the cultivation of cotton. Unlike tobacco, cotton did not need inspection. Consequently, cotton farmers transporting their crops to Augusta by river and road avoided the town altogether. Railroads completely bypassed the region, and steamboat navigation to the area was not possible because of rocky shoals and shallow water.

The cumulative effect of these problems was that by 1854 only three families remained in Petersburg, which was a decayed shell of its former glory. The last bit of excitement at Petersburg took place during the last phase of the Civil War (1861-65) in the spring of 1865, when Confederate president Jefferson Davis and his cabinet, fleeing from federal troops, crossed the Savannah River just below the town. Here, the Confederate government dispersed its treasury of gold and silver to accompanying troops and, according to some accounts, cast the golden seal of the Confederacy into the Savannah River.

The remnants of Petersburg succumbed to the waters of Clarks Hill Lake when the Corps of Engineers built the reservoir during the early 1950s. Today, Petersburg is the major historical attraction at Bobby Brown State Park in Elbert County. The town’s site is accessible to visitors through a wooded path that leads to the lake’s shore.