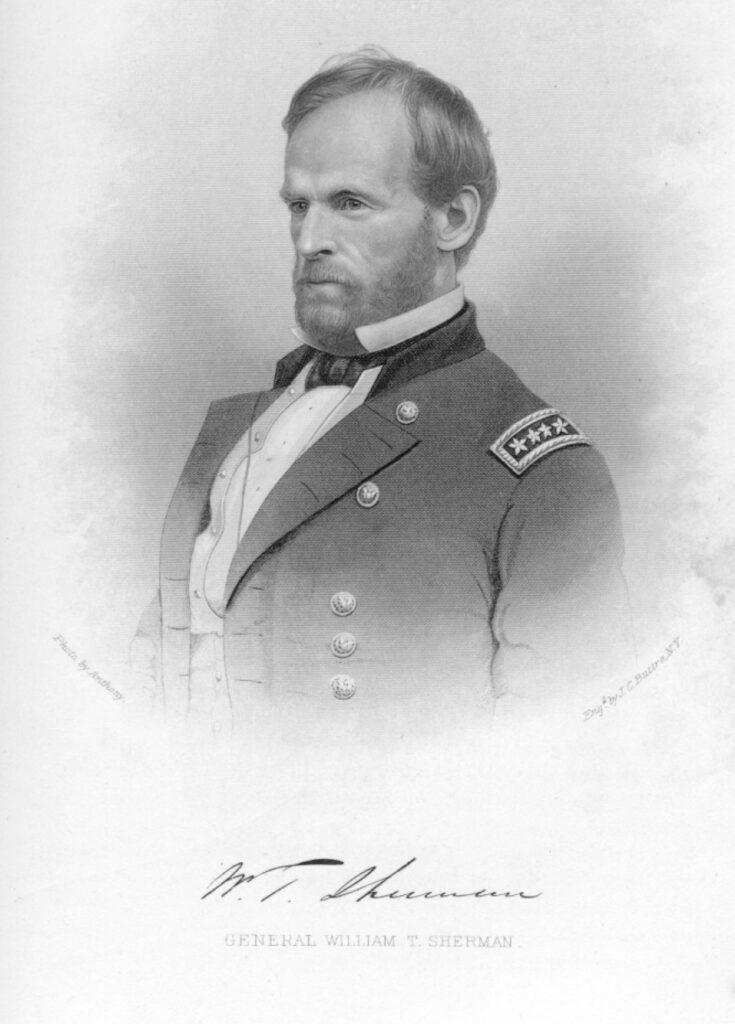

On January 16, 1865, during the Civil War (1861-65), Union general William T. Sherman issued his Special Field Order No. 15, which confiscated as Union property a strip of coastline stretching from Charleston, South Carolina, to the St. John’s River in Florida, including Georgia’s Sea Islands and the mainland thirty miles in from the coast. The order redistributed the roughly 400,000 acres of land to newly freed Black families in forty-acre segments.

From The History of the State of Georgia, by I. W. Avery

Sherman’s order came on the heels of his successful March to the Sea from Atlanta to Savannah and just prior to his march northward into South Carolina. Radical Republicans in the U.S. Congress, like Charles Sumner and Thaddeus Stevens, for some time had pushed for land redistribution in order to break the back of Southern slaveholders’ power. Feeling pressure from within his own party, U.S. president Abraham Lincoln sent his secretary of war, Edwin M. Stanton, to Savannah in order to facilitate a conversation with Sherman over what to do with Southern planters’ lands.

On January 12 Sherman and Stanton met with twenty Black leaders of the Savannah community, mostly Baptist and Methodist ministers, to discuss the question of emancipation. Lincoln approved Field Order No. 15 before Sherman issued it just four days after meeting with the Black leaders. From Sherman’s perspective the most important priority in issuing the directive was military expediency. It served as a means of providing for the thousands of Black refugees who had been following his army since its invasion of Georgia. He could not afford to support or protect these refugees while on campaign.

The order explicitly called for the settlement of Black families on confiscated land, encouraged freedmen to join the Union army to help sustain their newly won liberty, and designated a general officer to act as inspector of settlements. Inspector General Rufus Saxton would police the land and work to ensure legal title of the property for the Black settlers. In a later order, Sherman also authorized the army to loan mules to the newly settled farmers.

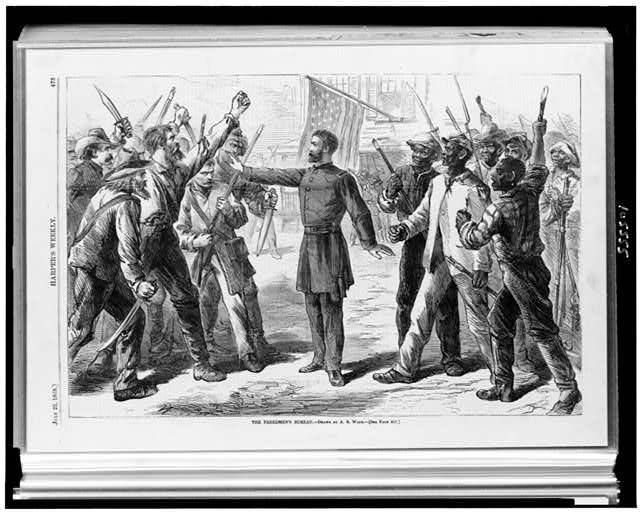

Sherman’s radical plan for land redistribution in the South was actually a practical response to several issues. Although Sherman had never been a racial egalitarian, his land-redistribution order served the military purpose of punishing Confederate planters along the rice coast of the South for their role in starting the Civil War, while simultaneously solving what he and Radical Republicans viewed as a major new American problem: what to do with a new class of free Southern laborers. Congressional leaders convinced President Lincoln to establish the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands on March 3, 1865, shortly after Sherman issued his order. The Freedmen’s Bureau, as it came to be called, was authorized to give legal title for forty-acre plots of land to freedmen and white Southern Unionists.

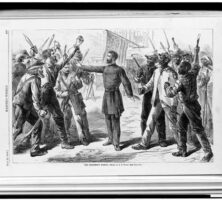

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

The immediate effect of Sherman’s order provided for the settlement of roughly 40,000 Black Americans (both refugees and locals who had been under Union army administration in the Sea Islands since 1861). This lifted the burden of supporting the freedpeople from Sherman’s army as it turned north into South Carolina. But the order was a short-lived promise for Blacks. Despite the objections of General Oliver O. Howard, the Freedmen’s Bureau chief, U.S. president Andrew Johnson overturned Sherman’s directive in the fall of 1865, after the war had ended, and returned most of the land along the South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida coasts to the planters who had originally owned it.

Although Sherman’s Special Field Order No. 15 had no tangible benefit for Black citizens after President Johnson’s revocation, the present-day movement supporting reparations has pointed to it as the U.S. government’s promise to make restitution to African Americans for enslavement. The order is also the likely origin of the phrase “forty acres and a mule,” which spread throughout the South in the weeks and months following Sherman’s march.