The siege of Savannah, the second deadliest battle of the Revolutionary War (1775-83), took place in the fall of 1779. It was the most serious military confrontation in Georgia between British and Continental (American revolutionary) troops, as the Americans, with help from French forces, tried unsuccessfully to liberate the city from its yearlong occupation by the British.

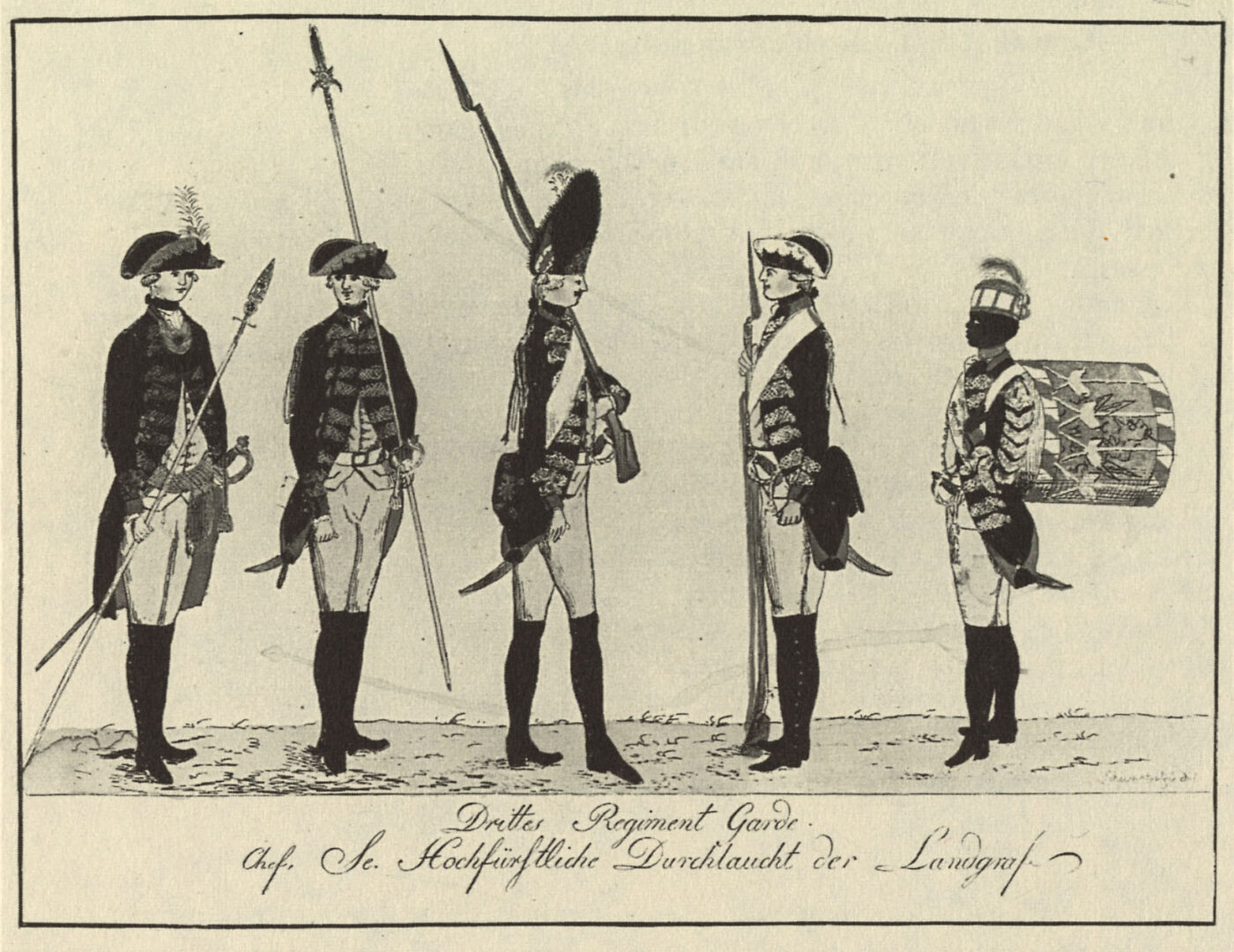

The Continental army’s failure to recapture Savannah marked a signal British victory in a distinctly international affair. Among the senior commanders fighting with the American revolutionaries (or Whigs) were Count Charles Henri d’Estaing of France, Arthur Dillon and his “Wild Geese” of Ireland, and Polish aristocrat Casimir Pulaski. Together, they faced the Tories, composed of British and Scots regulars joined by German mercenary troops (Hessians), American Loyalists, American Indians, and enslaved Africans.

France Joins the Revolution

French Royalists joined the North American rebellion against the British Crown after the defeat of British general John Burgoyne in 1777 at Saratoga, New York. On February 6, 1778, France signed both a treaty of amity and commerce and a treaty of defensive alliance with the newly established United States. French king Louis XVI then ordered d’Estaing, a senior officer in the French navy, to take command of the Toulon (Mediterranean) Squadron and sail for North America.

For the first time in French naval history, a French squadron crossed the Atlantic Ocean with the primary mission of combat. The squadron took part in the Battle of Rhode Island in August 1778 before capturing the West Indies islands of St. Vincent and Grenada in July 1779. In an undated letter, Charles-François Sevelinges (or the Marquis de Bretigny), a Frenchman in South Carolina service, wrote to d’Estaing and urged him to recapture Savannah, which had been under British control since December 29, 1778. He insisted that the city could be taken without firing a shot.

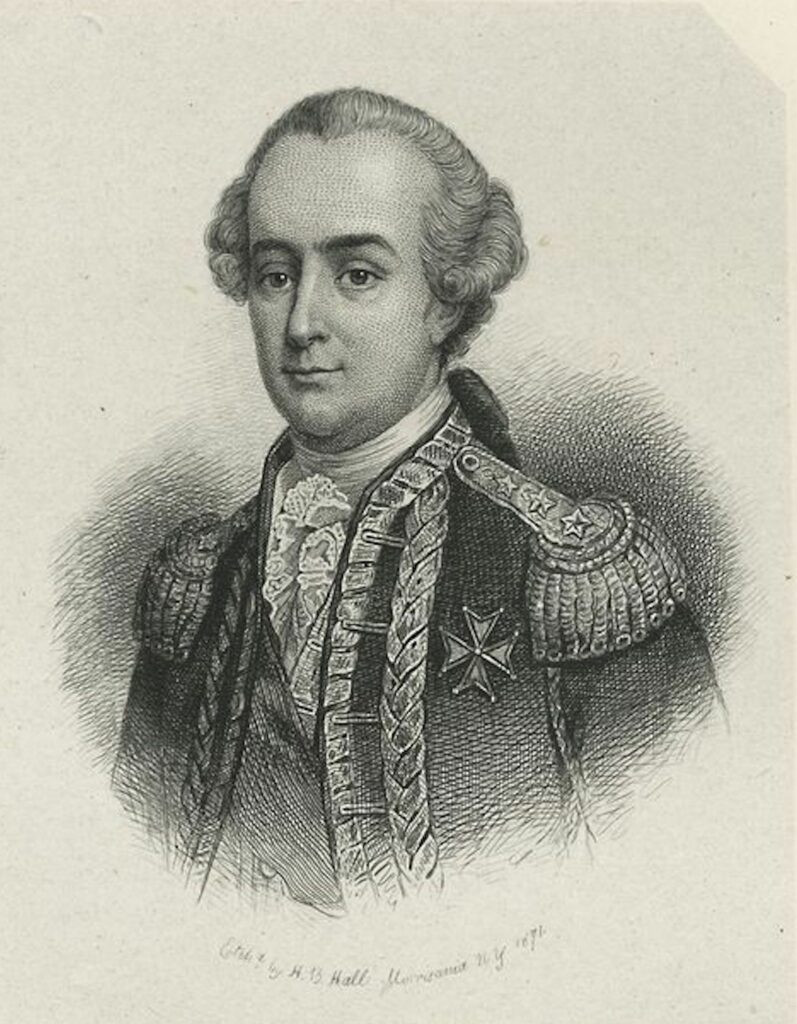

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

D’Estaing agreed. On September 3, 1779, a British lookout reported five French men-of-war approaching Tybee Island. The remainder of d’Estaing’s fleet, consisting of thirty-three warships and transports carrying more than 4,000 troops, reached Tybee Island on September 9. The French squadron arrived at the worst possible time of year, during hurricane season on the Georgia coast. While no hurricane developed during the siege of Savannah, the seasonal bad weather played a central part in its outcome.

Preparations for Battle

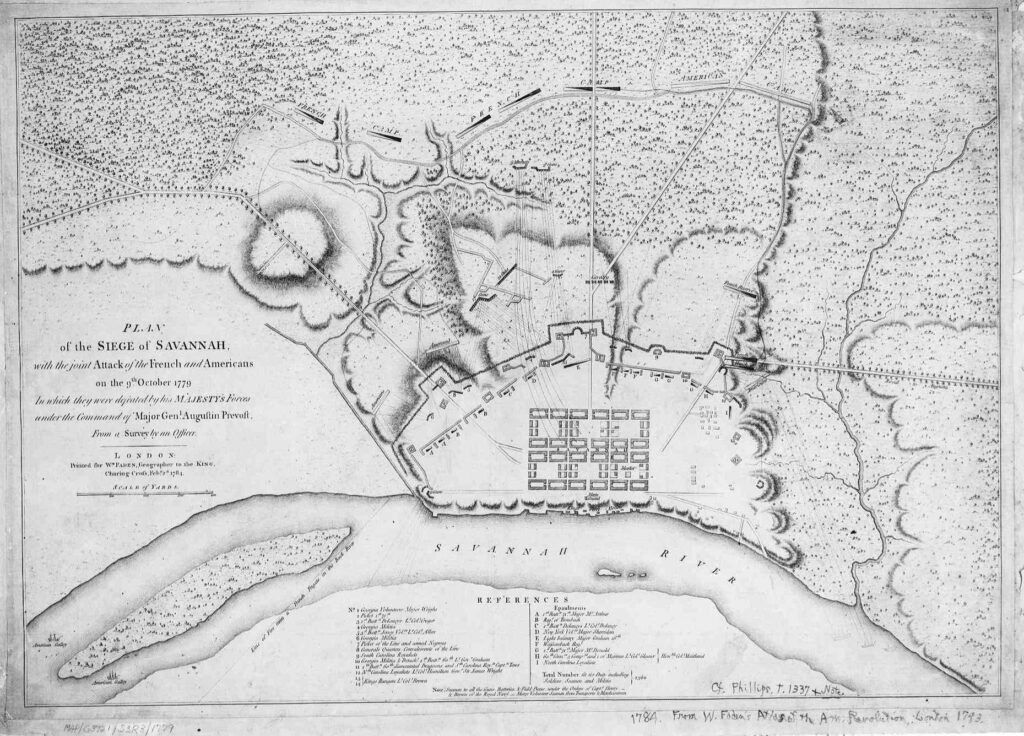

In Savannah, the British began work in earnest to improve their defenses. To block the French approach, they sank six ships in the Savannah River between Savannah and Tybee Roads (where the river’s estuary meets the Atlantic Ocean).

On the night of September 11 or 12 the French began landing operations at Beaulieu, fourteen miles south of Savannah on the Vernon River. Disembarking at night, without a pilot to guide them through the maze of waterways surrounding the city, the French struggled to find their way ashore. Some of the soldiers sat in open boats for three straight nights before landing. Once on land, the troops had no tents, and the rain reduced them to “a pitiable state,” in the words of one French solider. It took days for the disorganized forces to begin formal operations.

Image from Archives américaines, New-York

Meanwhile, the upcountry Whigs, despite being divided into radical and conservative political factions, managed to turn out a poorly equipped militia, which marched south to join the French. The ferrymen on the Savannah River struggled to get General Benjamin Lincoln’s long column of Continental and militia forces across the water. Liaison between these converging but separate allied forces was poor at best and even nonexistent at times.

General Lincoln finally reached Cherokee Hill, ten miles northwest of Savannah, with 600 Continental troops, 200 of Pulaski’s legionnaires, and 750 militiamen. On the morning of September 16, d’Estaing demanded that British general Augustine Prevost surrender the garrison at Savannah. Prevost delayed his reply, during which time British lieutenant colonel John Maitland and his force of 800 Scottish troops (Fraser’s Highlanders) arrived in Savannah after marching from Beaufort, South Carolina. With their arrival, British troops numbered 3,200, in addition to the numerous militiamen, Indian warriors, and armed Black Loyalists at Prevost’s disposal.

With their strengthened defensive posture, Prevost and his council of war agreed to reject d’Estaing’s demand for surrender. Whig general William Moultrie pressed for a swift attack on Savannah, but Lincoln and d’Estaing decided instead to open siege warfare with a bombardment of the city. On September 22 the French off-loaded their heavy ordnance at Thunderbolt and Causton’s Bluff, coastal communities adjacent to Savannah, and began hauling it overland some five miles. Their movement was delayed by heavy rains.

Courtesy of Georgia Historical Society.

The British, meanwhile, pulled down the brick barracks in the center of their lines and erected a great defensive work, or redoubt, in its place to cover White Bluff Road leading into Savannah from the south. The defenders constructed another redoubt on the northeast corner of their line at Trustee’s Garden. These main posts were defended by smaller redoubts and by a line of earthworks protected by an abatis—a closed row of sharpened stakes pointing outward and creating a formidable obstacle to any assault force, especially horsemen. In the Savannah River the armed brig Germain supported the northwest portion of the line. This ship covered the Sailors’ Battery, which in turn covered the strong redoubt at Spring Hill. A creek and thick swamp guarded Prevost’s western flank.

The Siege Begins

On the night of October 8, with more bad weather closing in, d’Estaing ordered his assault, which he intended to carry out as three coordinated attacks. A diversionary column of 500 South Carolina and Georgia militiamen, commanded by General Isaac Huger, made a feint—a false attack—toward the White Bluff Road redoubt in an attempt to draw British attention away from the main objective. The British met them with musketry and music, forcing Huger to withdraw.

Meanwhile, Whig-allied colonel Arthur Dillon’s Irish battalion moved secretly around to the northwest and conducted a second attack, aimed at the British right flank near the Sailors’ Battery. D’Estaing chose Major Charles-Noel-François Romand de l’Isle, the French officer who earlier had commanded Georgia’s Continental artillery, to guide Dillon’s command through the British defenses. The British had altered their fortifications, however, and Romand de l’Isle became confused, losing his way in the swamp. When Dillon’s assault force finally emerged in plain view of the British, his troops met with heavy fire and were driven back.

The Whig allies executed their main attack exactly where Prevost had predicted they would—against the Spring Hill redoubt on the Ebenezer Road, a sector of the British lines commanded by Maitland. Fully alert, the defenders awaited the allied forces in the redoubt.

D’Estaing’s strategy called for three French and two American columns to make a simultaneous assault at dawn, around 5 a.m. The French were to charge northeast across about 500 yards of open ground toward the Spring Hill redoubt, while the Americans were to form on the French left and charge Spring Hill from the west. The French, however, arrived late. Moreover, when the first French column reached its position on the right flank of the line of departure, d’Estaing immediately sent it forward before the other columns arrived.

The French battle cry “Vive le roi!” [Long live the king!] rang out while the Scottish bagpipes of the defenders greeted the assault. British grapeshot tore into the French column as it moved across the open plain, while those who reached the abatis protecting the redoubt fell to British musket balls. In spite of the French officers’ best efforts, their attack column broke away and sought the protection of the surrounding woods. As the second and third French columns moved into the attack, they met with the same fate as the comrades who had preceded them.

In the American zone, Pulaski waited for the infantry to breach the defensive lines so that he could lead his 200 horsemen on a charge through the gap. Colonel John Laurens’s 2nd Regiment South Carolina Continentals and the 1st Battalion Charleston Militia led the allied infantry advance. General Lachlan McIntosh followed with the 1st and 5th South Carolina Continentals, along with some Georgia regulars. They crossed the open area, swarmed into the ditch, hacked their way through the sharp-pointed abatis, and planted the flags of South Carolina and France on the earthworks. The British, in response, cut down the attackers and their colors, and launched an aggressive counterattack, led by the grenadiers of the 60th Regiment and a company of marines. The battle raged for nearly an hour. The defeated allies retreated, leaving 80 dead in the ditch and 93 more between it and the abatis. None of the French grenadiers had managed to get inside the redoubt.

Realizing the crisis and impatient to act, Pulaski left his cavalry under cover in the woods and rode forward to investigate the field. As he did so, word reached him that d’Estaing had been cut down with his men and was possibly dead. Pulaski, accompanied by his aide, Captain Paul Bentalou, rode forward to see the ground for himself. As he did so, grapeshot from either the Sailors’ Battery or the Germain—it is uncertain which—hit Pulaski in the groin, causing a mortal wound. Back at the woodline, his troops realized that a charge against the British defenses would be futile and began a retreat. As they moved into the swamp, the horsemen swept away part of Laurens’s command, causing Laurens to lose control of his scattered and disorganized units.

Aftermath of the Siege

Continental senior officer Thomas Pinckney returned to General Lincoln with the report that not one allied soldier was left standing in front of Spring Hill. The French withdrew to Causton’s Bluff and Thunderbolt, where they returned to their ships in the Savannah River and sailed away. Lincoln had no option but to withdraw to Charleston, South Carolina. The militiamen melted away.

The Whig allies lost about 1,094 killed, including about 650 French troops. In addition, Prevost returned to their commands some 116 wounded allies, most of them having received mortal wounds. British losses, according to General Henry Clinton, were 16 killed and 39 wounded. However, other sources claim that these figures include “King’s troops” only and do not count their Loyalist or German auxiliaries. Most authorities accept the figure of about 40 killed and 63 wounded. General Clinton declared that the defeat of the allied assault on Savannah was “the greatest event that has happened in the whole war.”

The immediate results of the siege of Savannah included a humiliating defeat for the French, the hardening of British policy against rebellious Americans in the South, and the realization by Georgia Loyalists and their British protectors that resistance in the upcountry must be crushed without mercy. Long-term results included the restoration of Georgia to colonial status. From this vantage, the British were able to expand their control north into the Carolinas and Virginia. Further, large numbers of Americans who had been somewhat indifferent to the conflict began to flock to the British standard, believing that the revolutionary enterprise was doomed to failure.