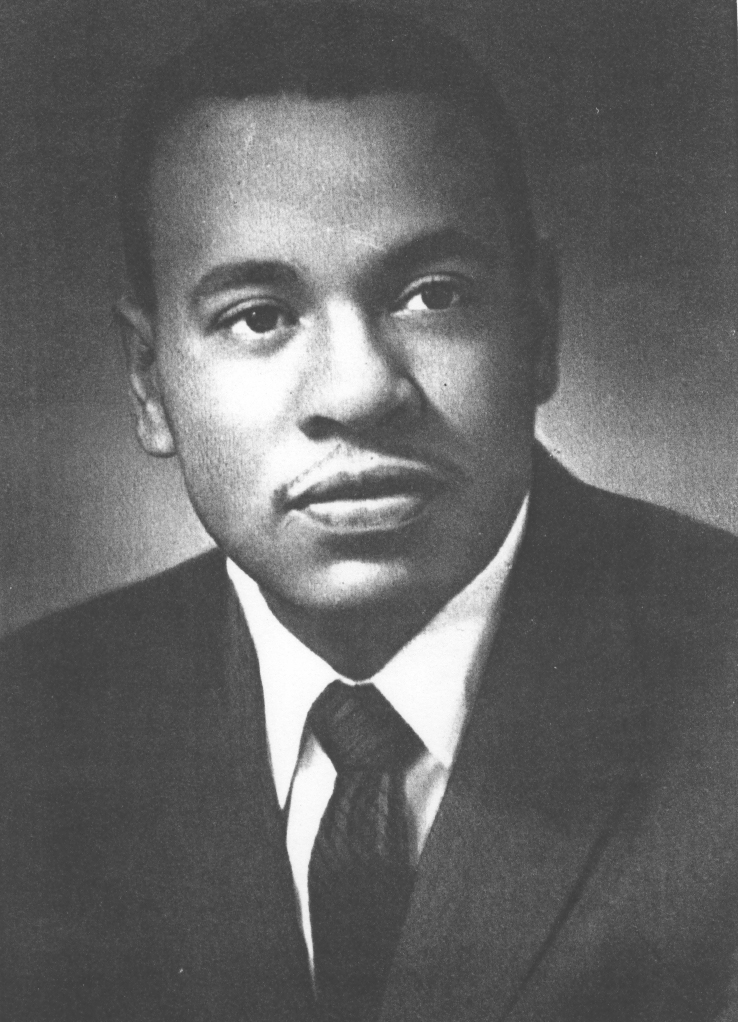

Civil rights activist Slater King was a successful realestate broker who focused his entrepreneurial skills on farsighted plans to help African Americans in Albany and Dougherty County achieve economic independence. Initially vice president of the Albany Movement, founded in 1961, King went on to assume the presidency after Americus-born osteopath William G. Anderson stepped down from the leadership role.

Early Life and Employment

Slater Hunter King was born on July 18, 1927, to Margaret Allegra Slater and Clennon Washington King. Along with two of his brothers, C. B. King and Preston King, Slater achieved regional and national distinction. The prominent and successful King family espoused an ethic based on work and community service, which influenced King’s efforts throughout his life. After high school he attended Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. Soon after receiving a B.A. in economics in 1946, he married Valencia Laverne Benham. They had two sons. After his divorce from Valencia, King married Marion Townsend in 1956.

After graduating from college King managed his father’s grocery store, then worked in a brokerage business, and finally was hired by the Aetna Insurance Company. His real estate business had begun to grow. With his wife, Marion, as administrative assistant, the operation expanded rapidly, necessitating a move to a new office building, which opened around 1965. There King worked next to, and often with, his older brother, the civil rights lawyer C. B. King. Eventually King’s brokerage firm employed as many as thirty people in various aspects of the business, which included real estate management and sales and insurance.

Civil Rights Movement

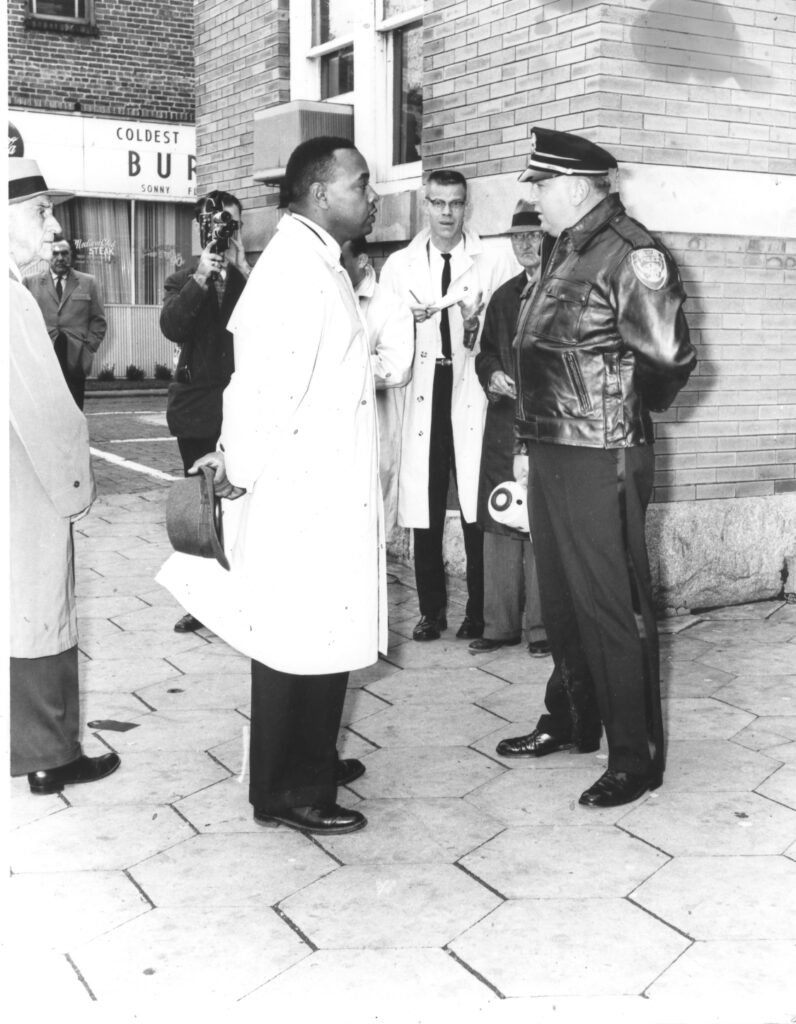

Following the lead of his father, who was a founder of the Albany National Association for the Advancement of Colored People chapter and of the social-needs-oriented Criterion Club, King was at the core of the development of the Albany Movement, a coalition of local African American organizations that united to protest injustice and segregation in the Black community. Elected vice president of the movement when it officially formed on December 17, 1961, King participated fully in the movement’s activities and was jailed for his participation. On more than one occasion he was jailed along with Martin Luther King Jr.

Courtesy of Cochran Studios/A. E. Jenkins Photography

A 1962 incident involving Marion King helped galvanize those who previously had not been as active in or supportive of local movement activities. Accompanied by two of her children, Marion traveled to a Mitchell County jail to deliver food and supplies to imprisoned civil rights protestors. She was told to leave, knocked to the ground, and kicked in the stomach by two policemen. Marion, who was six months pregnant at the time, lost consciousness—and later lost her child. At a mass meeting on the evening of the incident, Martin Luther King Jr. told the angry and grieving people, “It’s a terrible thing when a policeman hits a pregnant woman—a pregnant woman with a child in her arms.”

Courtesy of Cochran Studios/A. E. Jenkins Photography

Another incident involving the brutal treatment of African Americans by the Baker County sheriff ultimately led to Slater King’s 1963 arrest. The complicated case stemmed from the reaction in the Black community to the unjust trial of a Baker County man named Charlie Ware, who had been shot by the sheriff after he was taken prisoner. At Ware’s behest, C. B. King filed charges against the sheriff. The all-white jury set him free, and Albany’s Black community, in protest, boycotted the south Albany store of a juror who did not hire Black workers. Because of the boycott nine of the Albany Movement’s leaders, including King and Anderson, were charged with conspiring to obstruct justice. Ultimately, because of a nearly all-white jury, a mistrial was declared.

Courtesy of Cochran Studios/A. E. Jenkins Photography

Community Service and Development

King also worked to improve conditions within the African American community in Albany. He wrote letters locally to improve school conditions and obtain better school supplies, and sent the letters to Washington, D.C., and to civil rights organizations to bring the poor conditions to the attention of others. After the height of the Albany Movement in the early 1960s, the battle for freedom and equality remained a constant struggle for Blacks, but King’s letters reflect his effort to acquaint the wider world with the struggle in Albany. A March 1965 letter addressed to the U. S. Commission on Civil Rights and copied to U.S. president Lyndon B. Johnson informed the commission of the repeated failure of Dougherty County and the city of Albany to hold overdue civil-rights hearings and to alleviate discrimination and poverty.

Courtesy of Cochran Studios/A. E. Jenkins Photography

Other letters included in his correspondence are addressed to U.S. president John F. Kennedy, Black activist Malcolm X, New York congressman Adam Clayton Powell, educator and activist W. E. B. Du Bois, the Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions, the National Urban League, and the General Litigation Section of the U.S. Department of Justice.

King actively promoted socioeconomic development in and around south Albany and throughout the region. At the time housing was very limited for African Americans, and King used his real estate experience to purchase properties in some previously all-white areas and sell them to African Americans. King saw too that other housing needs for elderly African Americans were not being met. He envisioned an all-inclusive structure for people of all ethnic backgrounds. Although King was unable to secure sufficient funding for this project before his death, the Slater H. King Center was eventually built according to King’s plans.

Another of King’s projects was the development of low-income and church-sponsored housing units, for which he obtained grants and loans from the federal government, the city of Albany, and sympathetic private investors. These projects too were completed after his death in 1969.

Operative before that year was yet another project partially funded by the federal government. Observing the large number of jobless and ill-trained people in Albany, King applied for and received a large federal grant to assist with socioeconomic problems. The result was a very constructive and active facility in south Albany, the Dougherty County Resource Center.

King was killed in an auto accident in 1969 in Dawson. King’s death was a loss to Albany’s African American community in many respects. His reputation had earned him significant admiration, causing one visitor to remark, “If Slater had been white, he would have been mayor of Albany.”

King worked successfully in many arenas, but at the time of his death his loss was perhaps felt most in Albany’s arena of civil rights. In 1970 A. C. Searles, the owner of the African American weekly Southwest Georgian, said regretfully that the Albany Movement was dead, and “the only person who kept it alive was killed.”