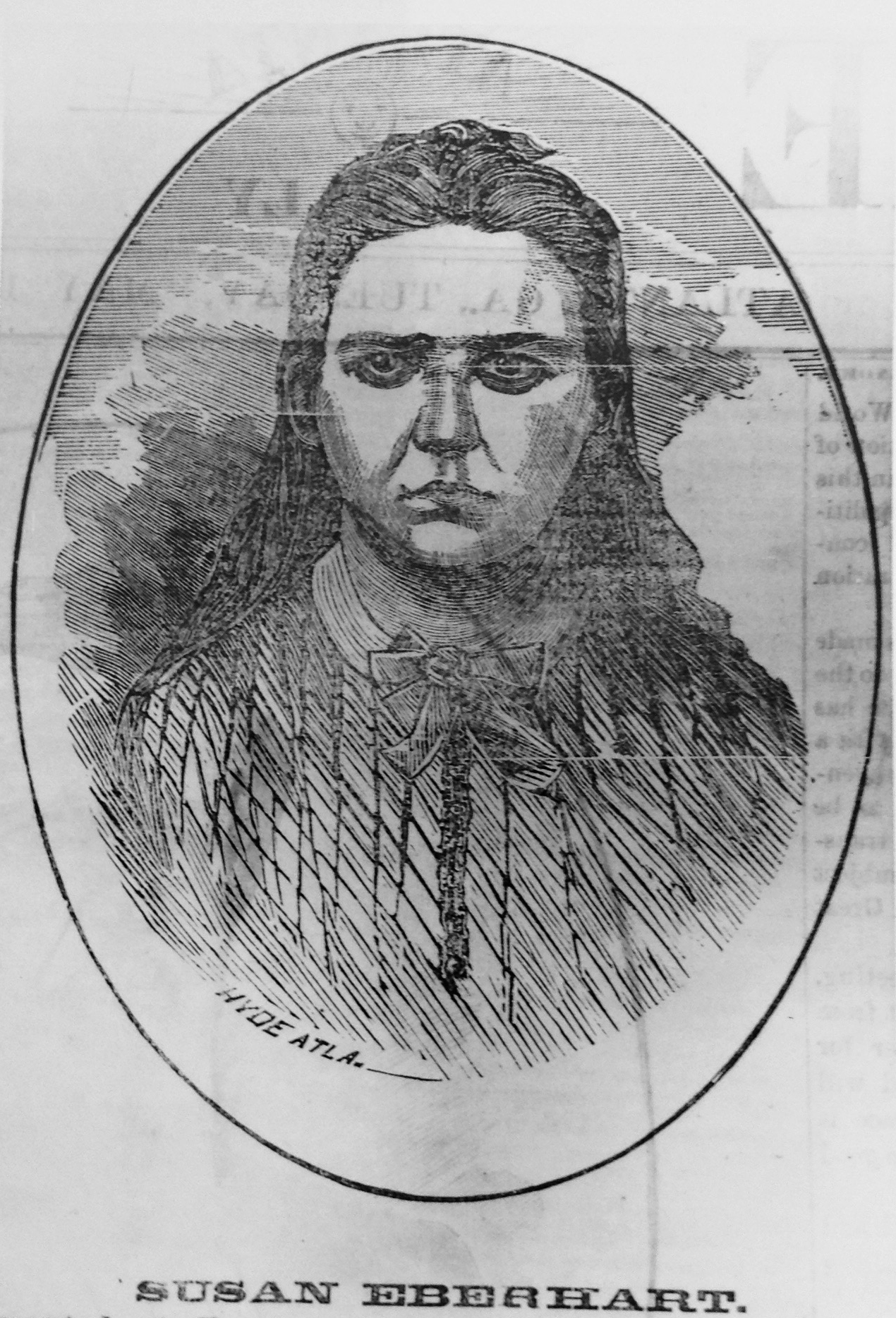

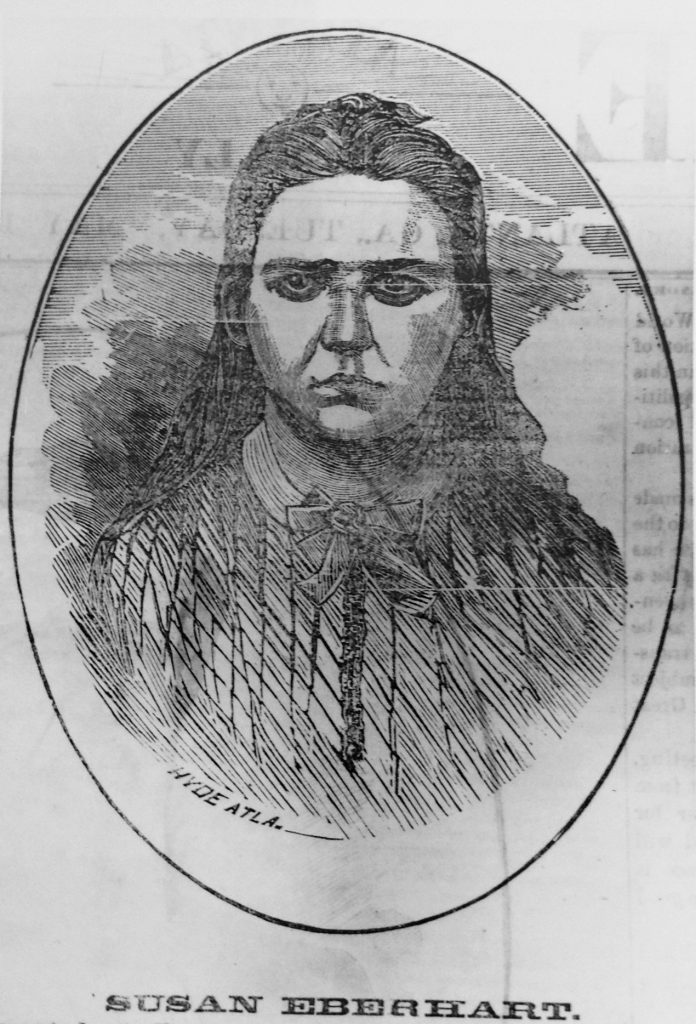

In 1873 Susan Eberhart was convicted of murder and hanged in Preston. Her execution was among the most publicized and controversial in the state’s history and had a significant influence on the administration of capital punishment in Georgia.

The Murder

In 1871 eighteen-year-old Susan Eberhart found employment as a servant for Enoch F. Spann, a thirty-six-year-old Confederate veteran, and his wife, Sarah, a disabled woman in her fifties. Enoch Spann made sexual advances toward Eberhart soon after her arrival and began plotting to murder his wife in hopes that he might marry Eberhart. Spann first arranged for his wife to be thrown from their buggy into a swollen stream while traveling to church, but Eberhart intervened and saved her from drowning.

According to rumor, Enoch then considered drowning his wife in a water barrel but never acted upon this plan. In May 1872 neighbors discovered Sarah Spann’s strangled body at the family’s home; Enoch Spann and Eberhart were nowhere to be found.

Governor James M. Smith offered a $500 reward for their capture, and a posse set out to locate the fugitives. A week later, the party found Spann and Eberhart in Alabama and returned the pair to Webster County to face trial. Members of the posse later testified that both fugitives admitted guilt, but the reward money may have motivated the ascription of blame.

Trials and Punishment

The Superior Court of Webster County found Spann and Eberhart guilty of first-degree murder and sentenced both to death by hanging. According to Enoch’s confession, he strangled his wife with a rope. Jurors debated whether Eberhart was an enthusiastic participant or a coerced victim, but ultimately concluded that Eberhart was guilty, having placed a handkerchief over the victim’s mouth to muffle her screams.

Spann later appealed his conviction on grounds of insanity, but a Webster County jury determined he had been fit to stand trial. Two unsuccessful appeals to the state supreme court followed, and on April 11, 1873, he was hanged on the gallows at “Bugger Bottom” in Preston. A carnival-like atmosphere prevailed as some 4,000 onlookers converged on Preston for the hanging.

Though her conviction also carried the death penalty, jurors urged the court to show Eberhart mercy based on their belief she had fallen under the malevolent influence of an older man. Lower courts disregarded that recommendation, however, and when Eberhart’s appeal reached the state supreme court, Justice H. K. McCay was unmoved; “We have had too much of this mercy,” he insisted.

Eberhart’s case was the subject of extensive coverage in state and national newspapers, and when her sentence was upheld, an array of sympathizers petitioned Governor Smith to spare her from the gallows. The governor refused, and subsequent attempts to influence Sheriff W. H. Matthews also proved unsuccessful. For her part, Eberhart claimed to be at peace, and observers described her as calm when approaching the gallows for her execution on May 2, 1873.

Fallout from the Eberhart execution continued in the years that followed. Haunted by his role in the affair, and by Eberhart’s prolonged suffering in particular, Sheriff Matthews died by an apparent suicide years later. Governor Smith’s reputation suffered grievously, and he was never again elected to office in Georgia. To avoid a similar fate, subsequent governors would not allow another white woman to be put to death until 2015, when Kelly Renee Gissendaner became only the fourth white woman to be executed in Georgia. Black women were executed on multiple occasions, however.