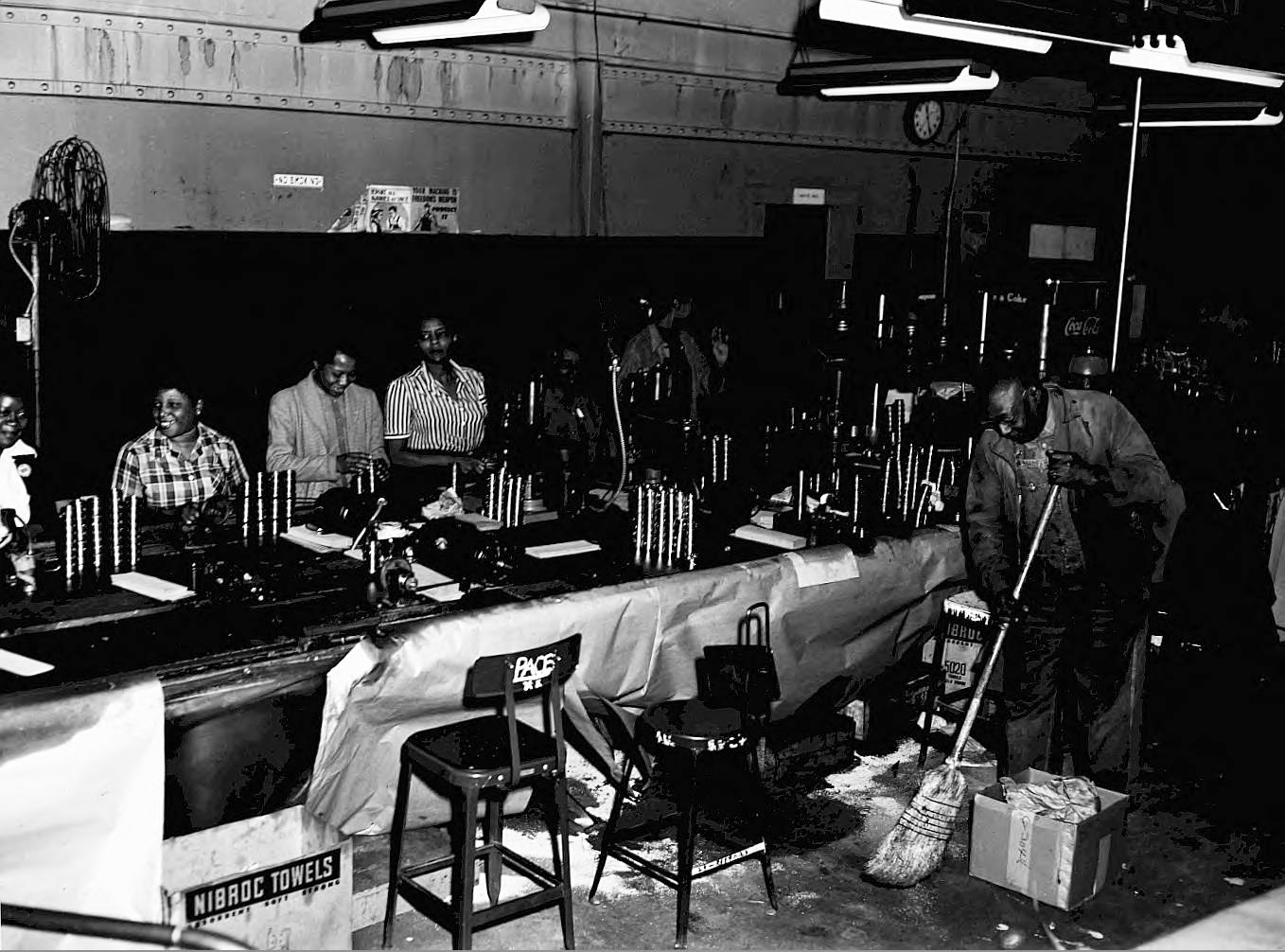

From 1931 to 1977, Scripto Inc. occupied a factory complex just east of downtown Atlanta. The company employed hundreds of Black Atlantans, primarily women, who manufactured ink pens, mechanical pencils, and cigarette lighters. During the factory’s tenure in the city, those women repeatedly organized to fight for higher wages, better positions, and an end to discrimination based on race and gender. These efforts were a significant precursor to the activism that would come to define the civil rights movement.

The Beginnings of Scripto

Scripto’s roots can be traced back to 1908, when the National Pencil Company opened its doors in downtown Atlanta. Atlanta businessman Sigmund Montag owned a controlling stake in the factory, which gained notoriety in 1913 when its superintendent, Leo Frank, was wrongly convicted of a murder that occurred at the plant. National Pencil went bankrupt shortly thereafter, and Montag sold the firm to his son-in-law, Monie Ferst, who renamed the company Atlantic Pen.

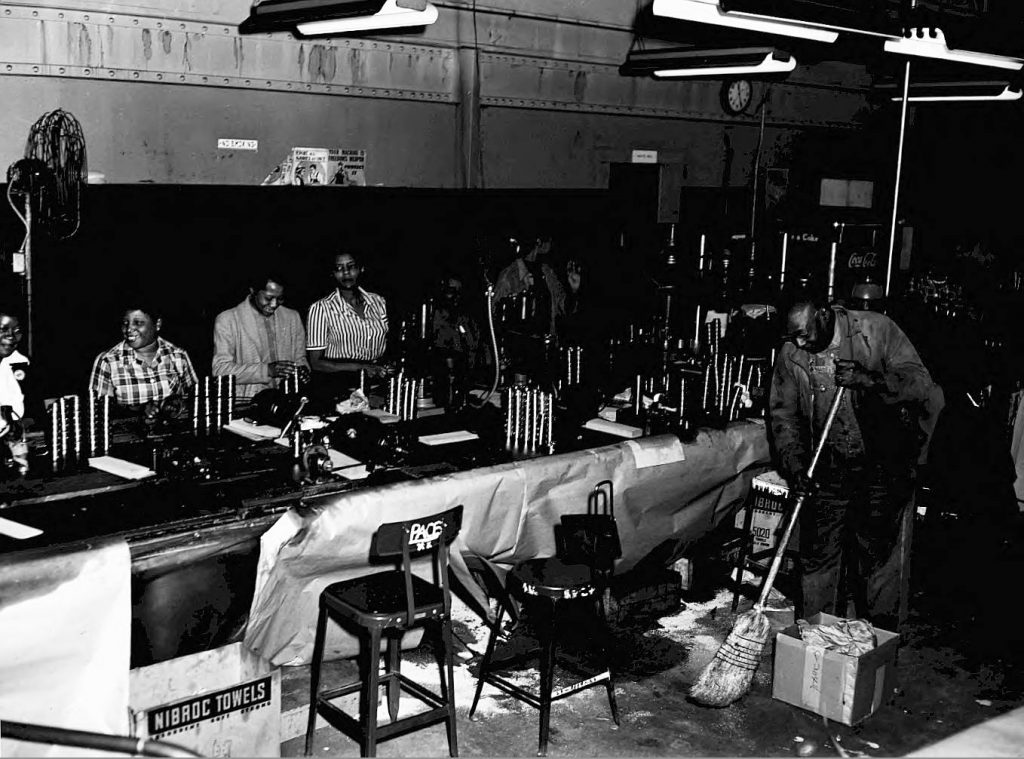

In 1931 Ferst moved the company to Houston Street (later John Wesley Dobbs Avenue), near Atlanta’s Black business and cultural district along Auburn Avenue. The plant, now called Scripto Inc., then began recruiting low-wage employees from the surrounding community. In the years that followed, Scripto embedded itself into Atlanta’s Black economic life, and company leaders prided themselves on offering what they considered fair wages and safe working conditions.

Scripto and the First Fights for Unionization

Black women turned to Scripto as an attractive alternative to domestic work in white households, and by 1940, they made up more than 80 percent of Scripto’s workforce. But accepting work at Scripto did not protect Black women from workplace discrimination. The United Steelworkers of America (USW) first attempted to organize the workers in 1940. Although their efforts failed—with USW organizers blaming the few white workers still on the payroll—Scripto’s workers called another union vote in 1946 to gain bargaining power in their negotiations with the company’s all-white management.

The USW ultimately won the worker’s approval with the help of Black community leaders like Martin Luther King Sr., pastor of the nearby Ebenezer Baptist Church, but Scripto’s management disputed the results and refused to grant the union a contract. On October 7, 1946, the USW called a strike to gain a contract, paid vacations, eight-hour shifts, and increased wages. More than 80 percent of the company’s 600 employees took to the picket line, where they faced intimidation from Scripto’s management and the Atlanta Police Department, which included known members of the Ku Klux Klan. With little to show for months of protest, the USW ended the strike on March 22, 1947. Scripto retaliated by firing all but nineteen of the striking workers, and when the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) found the company free of wrongdoing, the union suspended its efforts at the factory.

In 1952 the USW attempted to organize Scripto’s workers once more, this time focusing on employees in the company’s ordnance plant, which opened in 1951 to assemble artillery shell boosters for the Korean War. James V. Carmichael, an attorney, businessman, and occasional politician with a reputation as a racial moderate, had taken over as president of the company shortly after the end of the 1947 strike. Carmichael told the workers that he did not want either group organizing his workforce and would rather let the machinery rust than allow a union into the factory. The vote proceeded despite his wishes, and the workers again chose to join the USW. In response, Scripto fired the women most involved in the unionization efforts, and the ordnance division was shuttered two years later.

The 1964 Strike and Scripto’s Exit

The International Chemical Workers Union (ICWU) sought to organize Scripto’s workers in late 1962 by crafting an appeal that paired labor activism with civil rights. Their message was well received, and by the summer of 1963, the ICWU had gained enough support to petition the NLRB for a union vote. Carmichael once again expressed his disdain for organized labor, telling workers that he remained “one of the truest friends the Negro ever had in Georgia or in the entire South.” Unmoved by his paternalism, the workers approved the ICWU in September 1963.

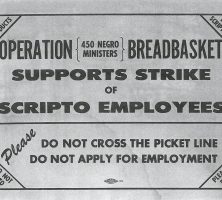

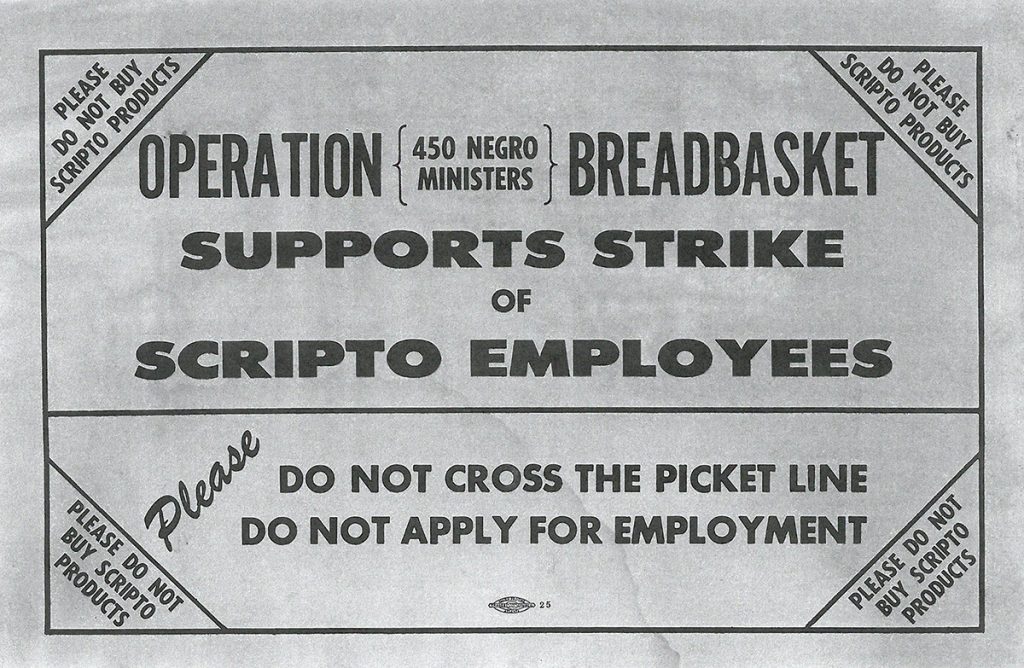

After Scripto’s legal team delayed the contract negotiations for months, 700 ICWU workers took to the streets the day after Thanksgiving 1964, demanding union recognition, increased wages, and an end to racial discrimination on the shop floor. Two Atlanta-based civil rights organizations, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), supported the strike, and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. joined the workers on the picket line. King had recently received the Nobel Peace Prize, and his involvement brought international attention to the fight at Scripto. Civil rights leaders also called for a boycott of Scripto products. On Christmas Eve, King met with Carl Singer, who succeeded Carmichael as president, to hash out a deal—a meeting arranged without the knowledge of ICWU leadership. King and Singer reached an agreement that won workers a Christmas bonus in exchange for calling off the boycott, but the ICWU felt that King had sold the workers short. Later meetings resulted in a deal that included union recognition and a four-cent raise, and the strike ended on January 9, 1965.

In 1977 Scripto moved its operations to suburban Doraville, ending the company’s investment in downtown Atlanta’s Black working-class community. The Japanese company Tokai Seiki bought Scripto in 1984 and moved the factory to California and then to Mexico. The Scripto factory building was razed during preparations for the 1996 Olympic Games, and the building’s former location now serves as a parking lot for the Martin Luther King Jr. National Historic Site.