In mid-March 1865, as the Confederate States of America struggled through its final days, Union major general James Harrison Wilson began a month-long cavalry raid that laid waste to much of the productive capacity of Alabama and Georgia.

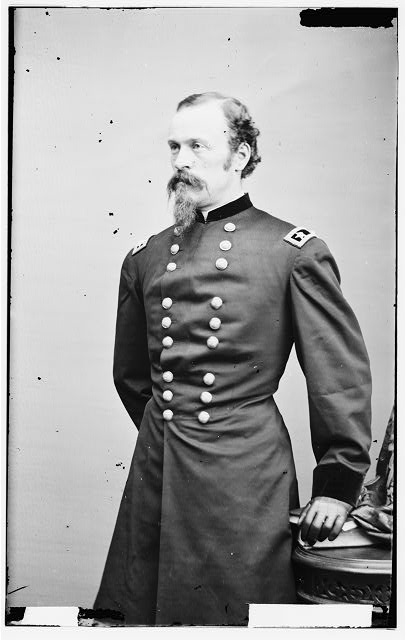

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

In a war where cavalry troops were underutilized, frequently mixed with infantry troops, or simply relegated to hauling supplies and delivering mail, Wilson’s approach to warfare was innovative: he used his 13,480 horsemen, without any infantry troops, in lightning quick raids against the productive centers of the Deep South. Much of the area from central Mississippi to central Georgia remained relatively unscathed, even in the late stages of the Civil War (1861-65). Consequently, cities like Selma and Montgomery, Alabama, and Columbus, Georgia, survived as vital shipping points and major producers of Confederate war supplies. Wilson’s aim was twofold: to destroy this critical supply link and to prevent the region from becoming the site of a Confederate last stand.

Wilson Begins His Raid

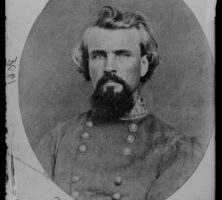

Wilson, the twenty-seven-year-old “boy-general,” a native of Illinois, graduated from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York, ranked sixth in his class in 1860. His star rose rapidly; he served under General William T. Sherman late in the war, after serving under General Ulysses S. Grant at Vicksburg, Mississippi, and Chattanooga, Tennessee, and heading the Cavalry Bureau of the War Department. Wilson began organizing and training his cavalrymen in northwest Alabama in early 1865. Because southern forces were preoccupied with stopping Sherman’s march to the sea, few Confederate troops were available to slow Wilson’s progress. General Nathan Bedford Forrest, with about 5,000 men, only 3,000 of whom were well mounted, constituted the main Confederate force in the region, but his troops were widely scattered and heavily outnumbered and outgunned.

Alabama

By March 31, 1865, Wilson and the main body of his force had worked their way to Montevallo in central Alabama, the heart of the state’s iron and coal district (just south of present-day Birmingham). Forrest’s troops offered ineffective resistance to Wilson’s men, who made quick work of the mills, coal mines, and foundries in the surrounding area, including facilities in Elyton (later Birmingham), Irondale, Oxmoor, and Brierfield.

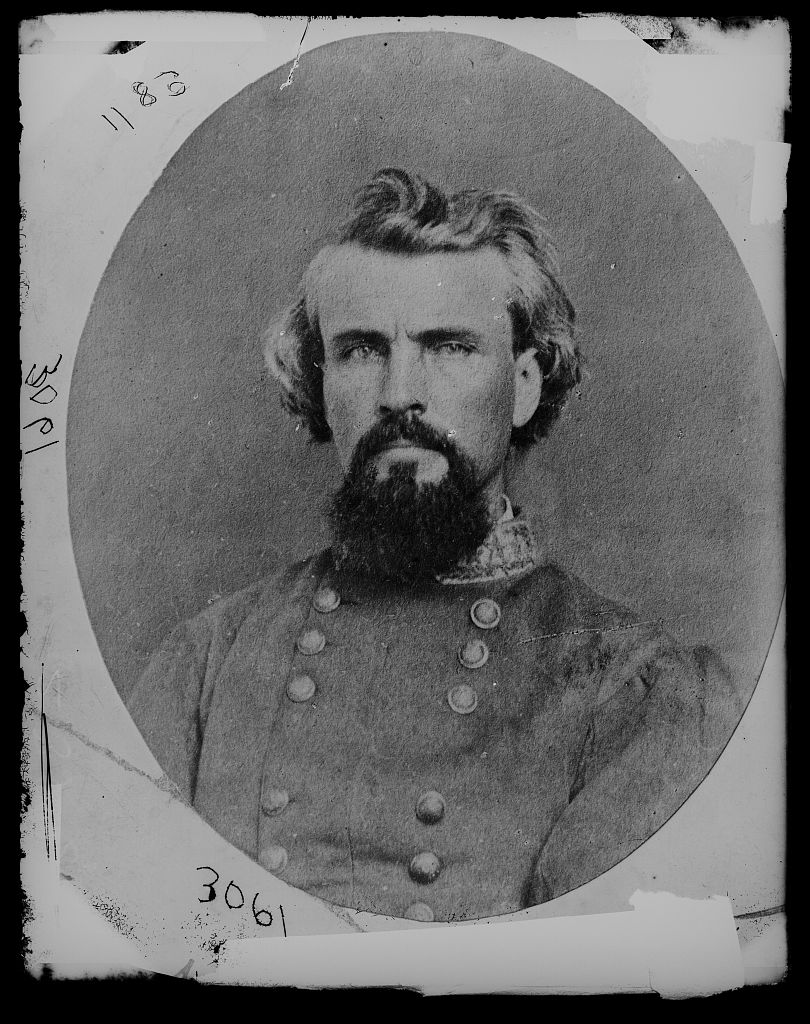

Forrest then concentrated his troops outside Selma as Wilson’s troops rapidly approached that city. The two sides clashed at Ebenezer Church some nineteen miles outside of Selma, with a decisive victory for the Union troops. Wilson lost only twelve men while inflicting considerably more damage on Forrest’s troops, with Forrest himself sustaining a minor injury.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Significantly outnumbered, Forrest hastily organized a civilian defense of Selma. Wilson moved against the city on April 2. Casualties were significant on both sides, but Wilson’s onslaught was too much. Forrest and his men fled the city in the middle of the night, putting the torch to the city’s cotton stores as they scrambled out of town.

With the fall of Selma, Wilson inflicted a considerable loss on the Confederacy. Selma’s arsenal contained, among other things, 15 siege guns, 60,000 rounds of artillery ammunition, and 1 million rounds of small arms ammunition. Wilson destroyed the city’s eleven ironworks and foundries, which had produced war goods for the Confederacy, as well as locomotives and rail cars, thus depriving the Confederacy of one of its last reliable industrial centers. Moreover, Forrest’s cavalry would harass Wilson’s forces no more. In a meeting between Forrest and Wilson, Forrest reputedly said to Wilson, “Well, General, you have beaten me badly, and for the first time I am compelled to make such an acknowledgement.”

As Wilson swung his troops eastward toward Montgomery, he faced increasingly diminished opposition. Like Selma, Montgomery was an important production center and a vital shipping point for distributing the region’s agricultural goods. Moreover, as Montgomery was the capital of Alabama and a former capital of the Confederacy, its taking carried considerable symbolic weight. As Wilson’s men approached Montgomery, Confederate general Dan Adams’s troops, charged with defending the city, were ordered to Columbus to link up with Howell Cobb’s Georgia State Troops. Montgomery was left defenseless, and Wilson’s men entered the city facing no resistance. With the war winding down, Wilson stayed in Montgomery two days, sparing the city except for its arsenal and its railroad equipment and depots.

Georgia

Heading into Georgia, Wilson moved against Columbus on April 16, 1865. Columbus, too, was unprepared to defend itself. Many of those tapped to defend the city were taking part in their first combat. Wilson easily routed the Confederates there and took around 1,500 men prisoner. With the fall of Columbus, Wilson had taken “the last great Confederate storehouse.” As Wilson headed for Macon, Confederate general Robert E. Lee had already surrendered at Appomattox, Virginia, and U.S. president Abraham Lincoln was dead. The war was effectively over.

Wilson organized cavalry patrols to capture fleeing Confederate leaders and to obtain the surrender of any bands of Confederates still roaming Alabama and Georgia. On May 10, 1865, a group of Wilson’s men captured the former president of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis, at Irwinville in south Georgia. Groups of Wilson’s men also captured or arrested former Confederate vice president Alexander Stephens, Georgia governor Joseph E. Brown, Georgia senator Benjamin Hill, and the infamous Henry Wirz, commandant of Andersonville prison. Wilson’s forces were fully disbanded by early July.

The Legacy of Wilson’s Raid

Although no one denies the tremendous damage Wilson’s men were able to inflict on the Confederacy’s productive abilities, scholars debate just how much damage Wilson’s troops inflicted on civilians and nonmilitary targets. A group of more than 13,000 men and horses moving through an area, foraging for food and supplies, was bound to cause damage against civilian property, whether or not the intent was malicious. It is certain that some depredations against civilians and civilian property occurred. Wilson’s Raid, however, should not be confused with Sherman’s march to the sea. As devastating as the raid was, its targets were largely military.

Historians have also debated the military necessity of Wilson’s Raid. By the time Wilson took Montgomery and Columbus, the war was effectively over, possibly rendering the damage inflicted on those cities gratuitous. It also will never be known whether any rogue Confederates would have or could have used Georgia, Alabama, or points further west for a last stand had Wilson’s Raid not occurred, although Wilson certainly made that possibility unlikely.

What is known is that in the course of a mere month, Wilson and his men covered hundreds of miles, took more than 6,000 men prisoner, and killed and wounded more than 1,000 Confederates, while having only 99 men killed and 598 wounded. Regardless of the timing that minimized the raid’s significance, this surprisingly deft and mobile force of more than 13,000 cavalrymen effectively destroyed the rail centers, arsenals, mines, and factories at the heart of the Confederacy.