Sharecropping was an agricultural labor system that developed in Georgia and throughout the South following Reconstruction and lasted until the mid-twentieth century. Under this arrangement, laborers with no land of their own worked on farm plots owned by others, and at the end of the season landowners paid workers a share of the crop.

Origins

Sharecropping evolved following the failure of both the contract labor system and land reform after the Civil War (1861-65). The contract labor system, administered by the Freedmen’s Bureau, was designed to negotiate labor deals between white landowners and formerly enslaved people, many of whom resented the system and refused to participate. In addition, despite some talk during and immediately after the war of land reform, in which the federal government would divide Confederate-owned plantations into smaller farms to be distributed to freedmen, most land was returned to its original owners. Instead of enjoying the often quoted “forty acres and a mule” that the government might have provided, freedpeople in Georgia were left with few options as laborers. Following the Civil War, plantation owners, without enslaved laborers or the money to pay a free labor force, were often unable to farm their land.

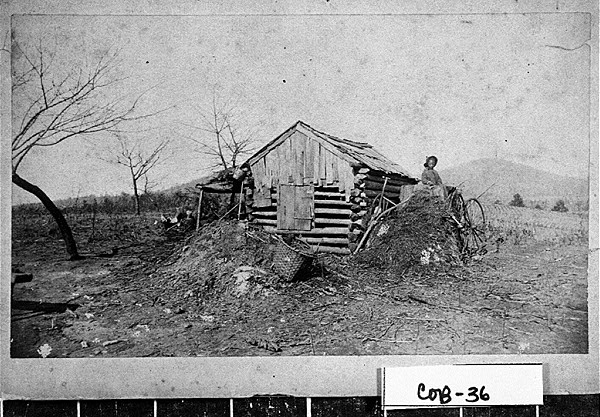

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

Sharecropping developed, then, as a system that theoretically benefited both parties. Landowners could have access to the large labor force necessary to grow cotton, but they did not need to pay these laborers money, a major benefit in a post-war Georgia that was cash poor but land rich. The workers, in turn, were free to negotiate a place to work and had the possibility of clearing enough profit at the end of the year to buy farm equipment or even land.

Though the system developed from immediate postwar contingencies, it defined the agricultural system in rural Georgia for close to 100 years. By 1880, 32 percent of the state’s farms were operated by sharecroppers; this figure would increase in the fifty years following. By 1910 sharecroppers operated 37 percent of the state’s 291,027 farms. Tenancy rates in general and sharecropping rates in particular were highest in those portions of the state that grew mostly cotton. In 1910, for instance, Burke, Dooly, and Houston counties led the state’s cotton production, and each had higher than average rates of tenant-operated farms and sharecropper populations.

The Labor System

The particulars of sharecropping agreements differed from place to place and over time, but generally those workers who could offer nothing but their ability to perform farm tasks made arrangements that overwhelmingly favored the landlord. In many cases, at the end of a season, a worker might be paid only one-third of the crop that he or she had produced. If a sharecropper and his or her family could provide something other than simply an ability to work—a mule, for example—then they might be paid with a slightly larger portion of the crop at the end of the season. Share-renters were laborers who could promise the landowner a fixed portion of the crop as payment for “renting” the land for a season. In this case the laborer might promise the landlord ten bushels of cottonseed in the fall as a fixed rent, and in turn the cropper would rely less on the landowner for support during the season.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

Land was not, however, the only thing sharecroppers needed from the owners. The owners of the state’s largest plantations would also sell fertilizer, seed, clothing, shoes, and some food from the plantation store. Croppers working smaller operations often bought these necessities from local furnishing merchants. The laborers rarely had cash, however, so in both cases they were extended credit to make purchases. In the fall, after harvesting the crop, landowners gave the workers their shares of the crop, often forcing the croppers to sell it straight to either the local furnishing agent or merchant, or even to the landowners themselves. With whatever cash the laborers made in this sale, they attempted to pay back the debt accrued during the season from the supplier.

This exchange was notorious for permitting landowners, creditors, and cotton buyers to defraud farmers. A sharecropper, often illiterate, rarely had the opportunity to check the books and add up his or her own debt, to calculate the interest, or even to shop his or her cotton to different buyers. Because of these limitations, sharecroppers often had little recourse when informed that proceeds from the sale of their crops were insufficient to settle debts accrued during the year. In such cases, workers were bound to the landlord for another season.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

Though much has been made of the system of peonage that kept sharecroppers in perpetual debt, tying workers to the same plantation year after year, there is significant evidence that Georgia croppers moved rather fluidly from place to place and from one form of labor to another. Certainly the reality of life as a sharecropper was a factor in the out-migration of rural Georgians in the 1910s and after. The sociologist Arthur F. Raper found in his study of Macon and Greene counties that of those Georgians fleeing the rural part of the state in the 1920s, the greatest numbers came from the ranks of sharecroppers.

Despite the common perception that sharecropping was a Black institution, sharecroppers were drawn from the ranks of all poor Georgians. In 1910, of the state’s 27 million farm acres, tenants operated 11 million acres; Black Georgians farmed slightly more than half of this tenant-tilled acreage. African Americans were, however, much more likely to farm land owned by someone else rather than to work their own land. Fewer than 16,000 farms were operated by Black owners in 1910, while during the same year African Americans managed 106,738 farms as tenants.

Sharecropper Life

For most sharecroppers, making money and paying off debts were not the only factors that mattered when it came to deciding whether or not to stay on a certain farm from one year to the next. In many cases a major factor was the extent to which the landowner attempted to control workers’ non-farm life. Though the owners instructed the croppers on how much acreage was to be planted in each crop, when the crops were to be planted and harvested, how much fertilizer was to be applied, and how the farm was to be run in general, the croppers had a degree of social independence.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

The plight of Georgia sharecroppers, in particular, received national attention with the publication of Erskine Caldwell’s best-selling novel Tobacco Road in 1932. Caldwell based his fictional family of poor white tenants, the hapless and increasingly desperate Lesters, on actual farm families he had observed in and around his boyhood home of Wrens, just southwest of Augusta, in Jefferson County. Along with photographer Margaret Bourke-White, Caldwell provided an equally effective nonfiction commentary on the impact of the Great Depression on Georgia’s poorest farmers in You Have Seen Their Faces, published in 1937.

Other nonfictional Georgia-based studies of sharecropping life and culture include several books by the sociologist Arthur F. Raper, who focused his attention on Greene and Macon counties in the late 1930s and early 1940s. Many years later, author Harry Crews’s memoir entitled A Childhood: The Biography of a Place (1978) provided vivid descriptions of his early life as part of a sharecropping family in depression-era Bacon County.

End of Sharecropping

Sharecropping in Georgia ended in the mid-twentieth century, in part because workers left the fields for southern and northern cities in what became the Great Migration. Black Georgians left the state for a variety of reasons, not least the greater degree of freedom afforded by northern states. For their part, poor whites left rural areas, too, often in search of better-paying industrial employment in the state’s growing cities. Tractors, mechanical cotton pickers, and other technological advances meanwhile allowed landowners to increase their yields with fewer workers and lower labor costs.

As a result of these dramatic changes, sharecropping—which had helped define the state’s economy during the century that followed the Civil War—had all but disappeared by the end of the twentieth century, when the U.S. census reported that fewer than 3,000 tenants tilled the soil in Georgia, with no special classification for sharecropping.