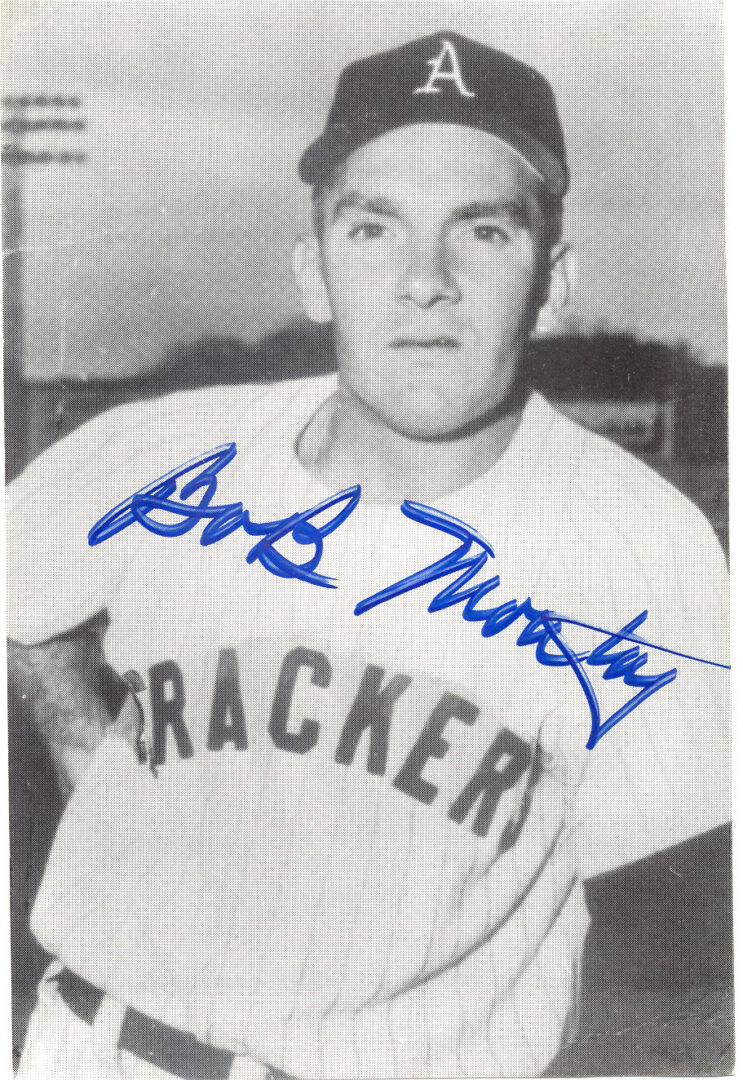

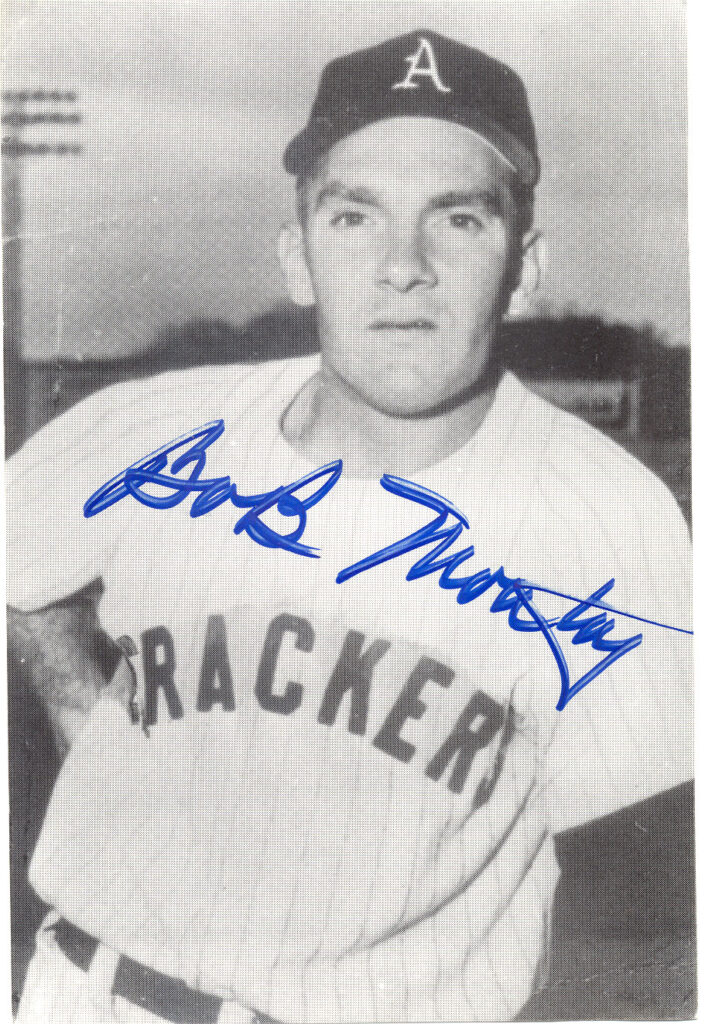

The slugging outfielder Bob Montag was the most popular player for the Atlanta Crackers in the 1950s. Even when he struck out, as he did frequently, the fans cheered and applauded him. When he retired as player-manager after the 1959 season, he had hit 113 home runs as a Cracker, the most in team history and the second highest in Southern Association League history. Many of them were long, majestic blasts that sailed far beyond the right field fence at Ponce de Leon Ballpark.

Courtesy of Bob Montag

Robert Edward Montag was born in 1923 in Cincinnati, Ohio. Wounded severely in World War II (1941-45), he earned a Bronze Star and a Purple Heart for his service. Despite doctors’ prognoses that he would never walk again, Montag went on to play all or part of seven seasons with the Crackers. His best year was 1954, when he hit thirty-nine home runs to establish a franchise record. He also set team records for the most walks and strikeouts in a season. In 1954 he and his teammates Chuck Tanner, Dick Donovan, and Leo Cristante led the Crackers to the AA Grand Slam, winning the midseason all-star game, pennant, postseason league playoffs, and Dixie Series over the champions of the Texas League. Only the 1938 Crackers had accomplished this feat.

In 1954 Montag hit what he claimed was the longest home run in baseball history. It landed in a coal car passing on the railroad tracks beyond the right field fence at the Ponce de Leon park. A few days later, after the train had gone to Nashville, Tennessee, and back, the conductor asked Montag to autograph the ball, which by that time had traveled more than 500 miles.

In 1949, when Montag played for Pawtucket in the Class B New England League, he enjoyed one of the best seasons in professional baseball since the end of World War II. By July 4 he was batting .505. He finished the year leading his league in every important offensive category except runs batted in, and his .423 batting average was the highest in organized baseball that season.

In spite of his offensive power, Montag never had a major league at-bat. He was a liability on defense, and he had a weak throwing arm. After retiring from baseball, Montag worked in Atlanta as an advertising salesman for TV Guide magazine. To honor him for his volunteer work, the American Federation for the Blind created the Robert Montag Youth Award. In 1998 he moved to Temecula, California, where he died on March 21, 2005.