Ponce de Leon Ballpark in Atlanta was one of the nation’s finest minor league baseball facilities in the early to mid-twentieth century. The original ballpark was built on property northeast of downtown owned by the Georgia Railway and Electric Company, directly across Ponce de Leon Avenue from an amusement park. A lake on the site was drained, filled in, and converted into a $60,000 ballpark made of wood. More than 8,000 fans welcomed the minor league Atlanta Crackers to their new home on May 23, 1907.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

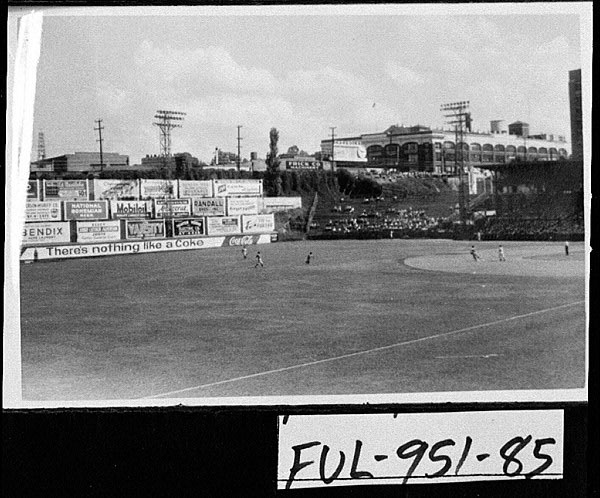

In 1923 the wooden ballpark burned down, and the Crackers finished out the season at Grant Field. Then a wealthy concessionaire named Rell Jackson Spiller spent $250,000 to build a concrete-and-steel baseball park. When R. J. Spiller Fieldmade its debut in time for the 1924 season, the Atlanta paper City Builder called it “the most magnificent park in the minor leagues.” The new facility drew lavish praise from baseball officials across the country. Chairs were fastened into the stadium’s new concrete skeleton, furnishing seats that were far more comfortable than the wooden benches fans used to occupy. The grandstand’s entire capacity was 9,800. The bleachers for the white fans, located in right field, accommodated 2,500, and the seats in left field, for African Americans, held the same number. With standing room for more than 6,000, the stadium could hold 20,000 fans.

Courtesy of Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

The fence was 365 feet down the left field line, 321 to right, and 462 to dead center, where a giant magnolia stood. Spiller Field had the only ground rules in baseball history allowing for a tree in the outfield. (One year, during a preseason barnstorming tour, Babe Ruth and the New York Yankees came into town. Ruth and his fellow Hall of Famer Eddie Mathews are the only two men ever to have hit home-run balls into the magnolia.)

When the park opened, there was a swimming pool next door where fans could go if the game got a little slow. Train tracks ran above the first-base line, and engineers frequently stopped their trains to watch the games. Across the street were horse stables, as well as a Spiller-owned restaurant, where alligator wrestling was an attraction.

Fans could also entertain themselves by gambling, which Georgia law allowed when it wasn’t conducted under a roof. The covered grandstands became home to the true Cracker faith ful, and the outfield bleachers were host to the “fly-ball fans,” who sat with the local oddsmakers. People would bet on anything, including on whether an outfielder would drop a routine fly ball. Buster Cheatham, a shortstop for the Crackers in the 1920s, probably saved bookies more money than any minor leaguer in history with his spectacular outfield catches. Once a group of bookies gave him a pot of about $200 in appreciation. Cheatham, afraid that people would think he had been corrupted, gave it back.

Photograph courtesy of Chris Dobbs.

Soon Cracker officials began prohibiting gambling during games, so bookies and their customers devised another language: finger signals. While the police roamed the stands looking for perpetrators, the bookies were paying or collecting from their customers. According to one story, a well-dressed businessman sitting in the outfield bleachers was holding up a couple of fingers, trying to make change with a vendor, when the police threw him out under suspicion of gambling.

The Crackers called Ponce de Leon Ballpark home until their final season in 1965, when they moved into the newly built Atlanta Stadium (later Atlanta