The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, or SNCC (pronounced “snick”), was one of the key organizations in the American civil rights movement of the 1960s. In Georgia SNCC concentrated its efforts in Albany and Atlanta.

Courtesy of David Fankhauser

Emerging from the student-led sit-ins to protest segregated lunch counters in Greensboro, North Carolina, and Nashville, Tennessee, SNCC’s strategy was much different from that of already established civil rights organizations. In April 1960, on the Shaw University campus in Raleigh, North Carolina, students of the sit-in movement met with Ella Baker, executive secretary of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and they established SNCC. SNCC sought to coordinate youth-led nonviolent, direct-action campaigns against segregation and other forms of racism. SNCC members played an integral role in sit-ins, Freedom Rides, the 1963 March on Washington, and such voter education projects as the Mississippi Freedom Summer.

The Albany Movement

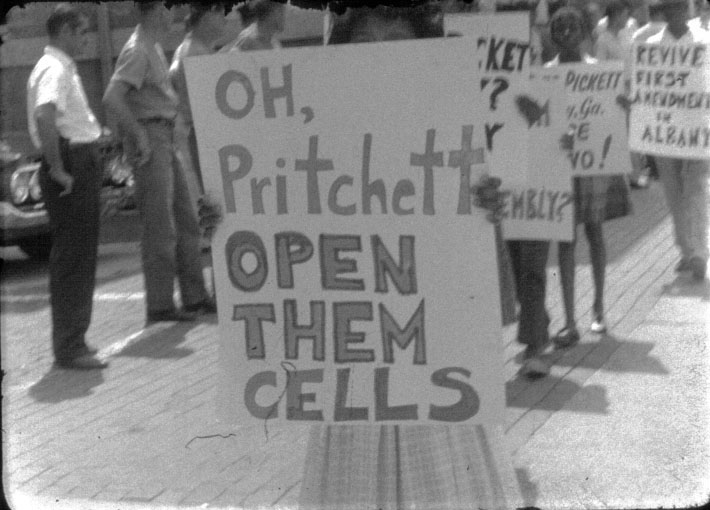

In October 1961 SNCC field secretaries Charles Sherrod and Cordell Reagon arrived in Albany to establish a voter registration office and to test local compliance with the Interstate Commerce Commission’s ruling, which barred segregation in interstate transportation terminals.

Within two months Sherrod and Reagon, joined by Charles Jones, helped to form the Albany Movement—a coalition of SNCC volunteers, the Youth Council of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the Baptist Ministerial Alliance, the Federation of Women’s Clubs, the Negro Voters League, and other groups. The movement coordinated mass rallies and demonstrations to protest the arrests of Black residents attempting to integrate the city’s bus and train terminals.

Courtesy of Walter J. Brown Media Archives and Peabody Awards Collection, University of Georgia Libraries.

Although the sit-ins and voter registration drives in Albany were slow to produce concrete results, the Albany Movement produced the largest direct-action campaign since the bus boycotts in Montgomery, Alabama. As a result, civil rights activists learned to organize mass demonstrations that would provoke the federal government to intervene. Martin Luther King Jr. was arrested in Albany three times, and he left the city for good in August 1962, admitting that the goals of the Albany Movement were still unmet. In 1965 King argued that the campaign failed due to the lack of focus on a particular harm: “The mistake I made there was to protest against segregation generally rather than against a single and distinct facet of it. Our protest was so vague that we got nothing, and the people were left very depressed and in despair.”

SNCC and local activists had a more optimistic view of the campaign’s outcome. “Now I can’t help how Dr. King might have felt,” Sherrod later said, “but as far as we were concerned, things moved on [in Albany]. We didn’t skip one beat.” Thanks to voter registration drives, African American businessman Thomas Chatman secured enough votes in a city commission election to force a run-off in late 1962, and in the spring of 1963 the commission removed all segregation statues. The protests demonstrated not only the appeal of SNCC to urban Blacks but also the importance of the church and religious beliefs as a foundation for mass struggle among Blacks in general.

Atlanta

Atlanta was also a center for SNCC activity. Home to a sizable Black professional and middle class and five historically Black colleges and universities, Atlanta was also King’s birthplace and home to the SCLC. In October 1960 SNCC held its second conference in Atlanta and chose the city as its headquarters. Immediately following the conference, SNCC staged massive sit-ins at the lunch counters of several Atlanta department stores, including Rich’s. Several students were arrested, as was King.

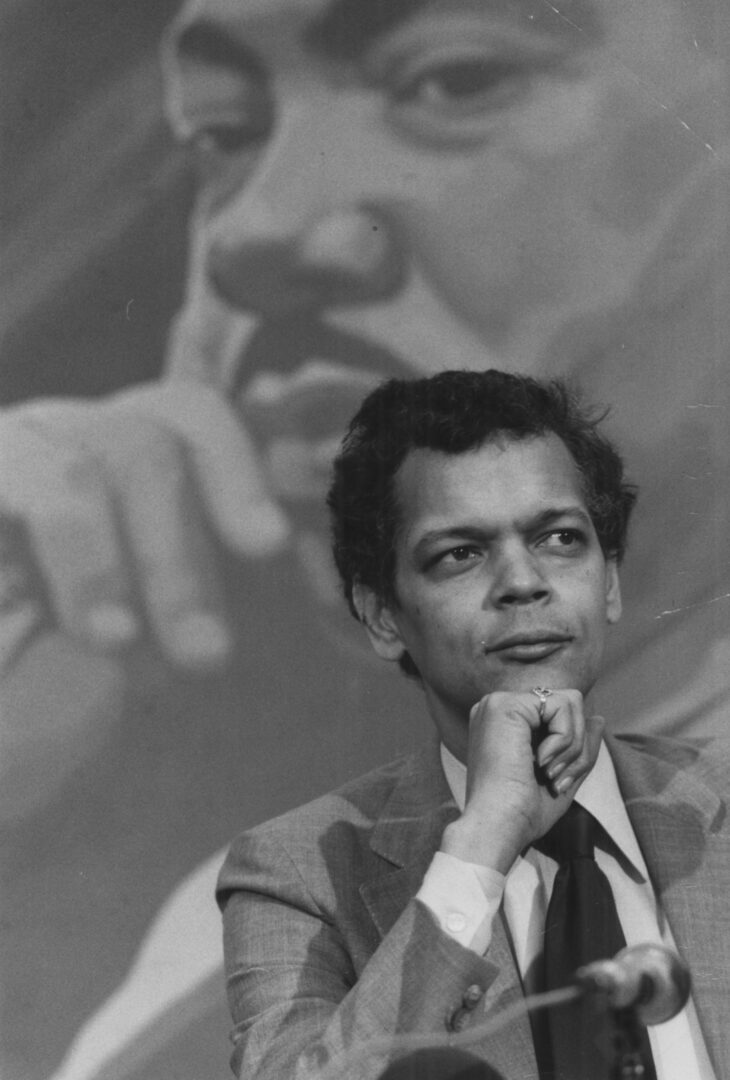

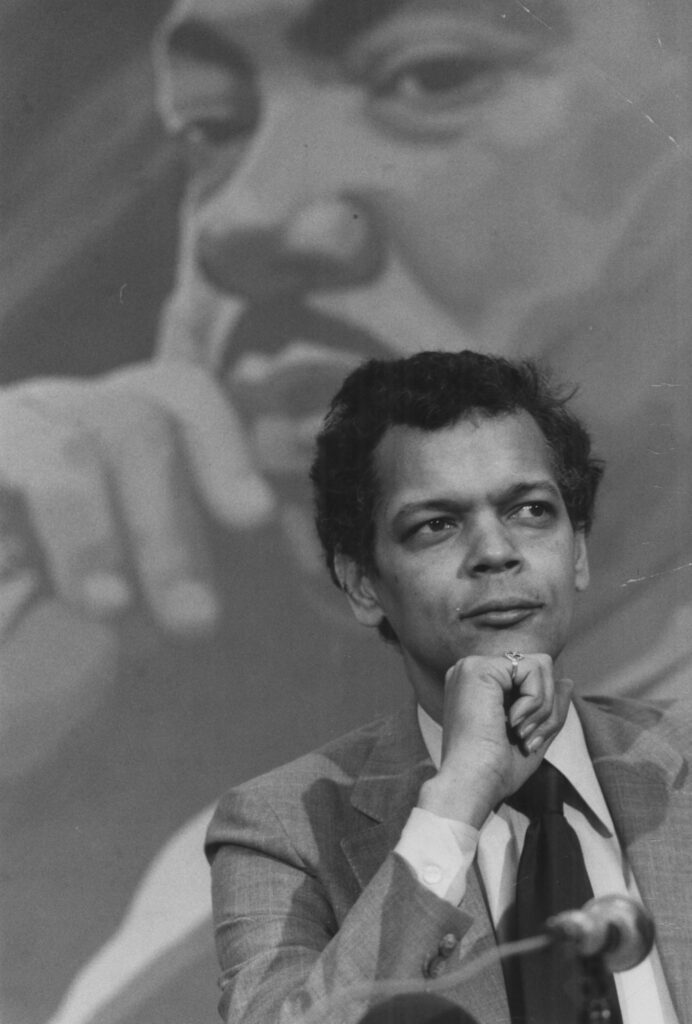

Soon after the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party failed to unseat the state’s all-white delegation at the 1964 Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, New Jersey, SNCC volunteers returned their attention to Atlanta. The U.S. Supreme Court ordered reapportionment for the Georgia state legislature during the 1964 General Assembly session, creating several new voting districts. Fulton County and the city of Atlanta, which together had only three legislators, gained an additional twenty-one seats. A reapportionment election was held on June 16, 1965, and Julian Bond, the longtime SNCC communications director, was elected to the 136th district, defeating a local minister and the dean of Atlanta University (later Clark Atlanta University). During the campaign Bond emphasized personal contact, going door-to-door and asking residents in the all-Black district what was needed. Concluding that their problems were largely economic, he devised a platform that included a $2 minimum wage, improved urban renewal programs, the repeal of the right-to-work law, and an end to the literacy test for voters.

Courtesy of Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

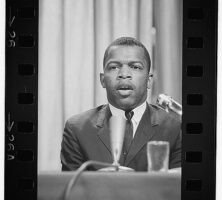

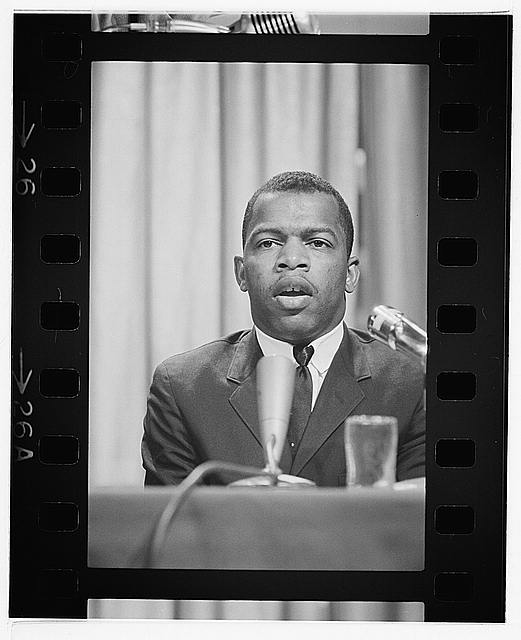

The Atlanta Project

SNCC changed dramatically in direction and philosophy during 1966, when Stokely Carmichael succeeded John Lewis as chair of the organization. The change came about in part because of the new Atlanta Project. Headed by Bill Ware, the Atlanta Project emerged in the wake of riots in the African American communities of Vine City and Summerhill (which were in Bond’s district). The Atlanta Project aimed to increase Black community “control over the public decisions which affect” their lives. According to historian Clayborne Carson, project members emphasized racial identity as a means to eliminate racial inferiority and political impotence and, unlike SNCC members, embraced racial separatist doctrines. Although Carmichael initially opposed Atlanta Project staff, he became greatly influenced by many of their positions, some of which he adopted as SNCC chairman.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

The separatist nature of the Atlanta Project ran counter to the national SNCC leadership, and within a year after Carmichael assumed SNCC leadership, he had fired all Atlanta Project workers, effectively ending the program. The project’s spirit would live on through such federally sponsored programs as Model Cities.

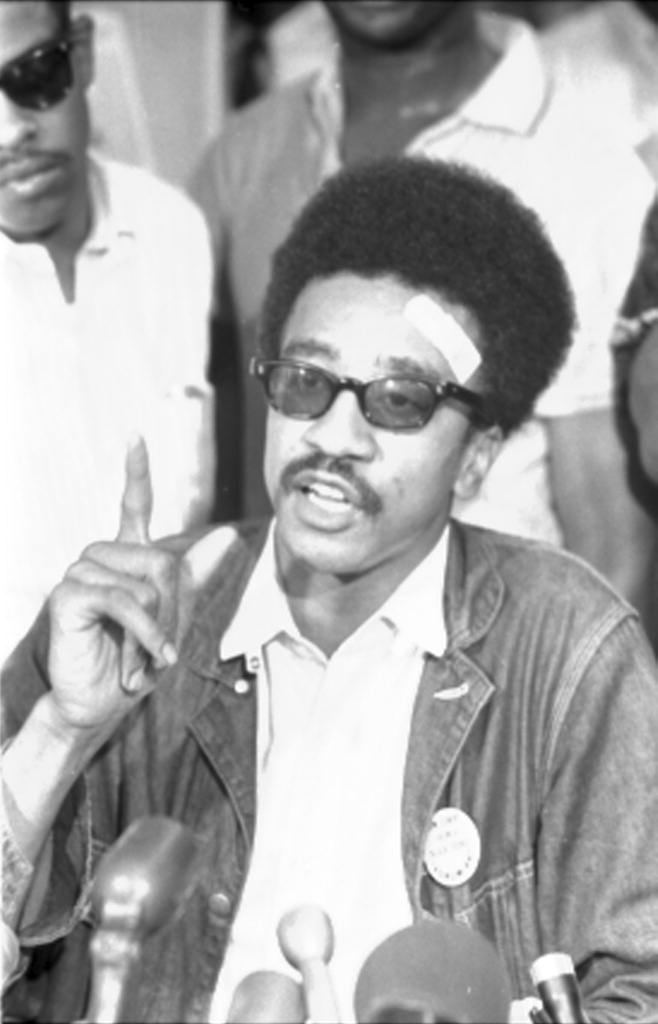

The Demise of SNCC

Despite his firing of the Atlanta Project staff, Carmichael came to embrace racial separatism, eject SNCC’s white members, and issue a call for Black Power, which emphasized racial dignity, Black self-reliance, and the use of violence as a legitimate means of self-defense. Under Carmichael’s successor, H. Rap Brown, SNCC became more controversial. During Brown’s tenure, SNCC increasingly collaborated with the Black Panther Party, a radical political organization founded in 1966 in Oakland, California, that attracted a similiar demographic as SNCC—young, urban African Americans. Members of the Black Panther Party rejected the nonviolent principles that dominated the civil rights movement. In 1968 Brown changed SNCC’s name, substituting “national” for “nonviolent.” By that time SNCC bore little resemblance to its original form. Facing legal troubles, Brown went into hiding in 1970, and what remained of the organization quickly unraveled.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division