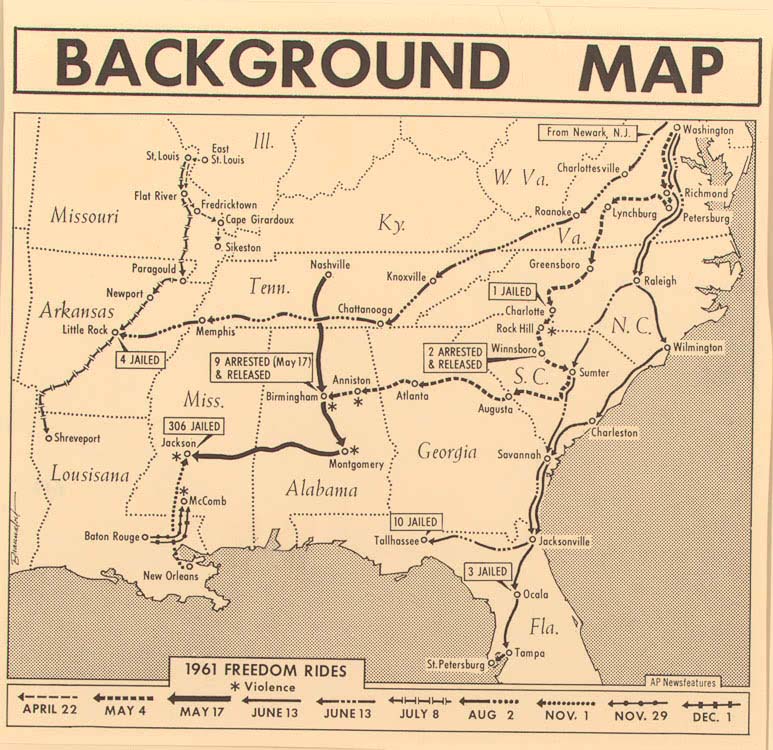

To test compliance with recent court rulings barring segregation in interstate travel, the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE) sponsored a series of integrated bus rides throughout the South in the spring and summer of 1961. Known thereafter as the Freedom Rides, the protests galvanized national support for civil rights reforms and compelled federal engagement in the African American freedom struggle. Although they met with violent resistance elsewhere in the region, Freedom Riders traveled unmolested through Georgia and were served courteously at multiple lunch counters throughout the state.

Background

Even as the civil rights movement gathered momentum in the early 1960s, many leading activists expressed frustration with the slow pace of change. Apart from perfunctory promises to uphold the law, officials in U.S. president John F. Kennedy’s administration remained on the sidelines of the struggle, and even national observers who favored civil rights reforms expressed ambivalence toward direct action protest. In 1960, however, when the U.S. Supreme Court issued its landmark judgment barring segregation in bus and train terminals in Boynton v. Virginia Supreme Court, CORE organizers recognized an opportunity to galvanize national support for their cause and, perhaps more important, to compel federal involvement in the African American freedom struggle. To gauge compliance with the ruling, CORE director James Farmer announced in February 1961 that his organization would sponsor a series of integrated bus rides throughout the South.

Courtesy of David Fankhauser

Though controversial, the idea itself was not new. In the wake of a similar ruling barring segregation on interstate buses fourteen years earlier, CORE activists launched a protest called the “Journey of Reconciliation.” Like the Freedom Rides, the Journey of Reconciliation featured an interracial team of activists that defied local customs and laws by riding in sections of interstate buses reserved for members of the other race. However, unlike their predecessors, whose travels were limited to the Upper South, the Freedom Riders charted a path through the Deep South, where violent resistance was all but certain.

Traveling through Georgia

Following a careful selection process and a weekend of intensive training in the methods of nonviolent protest, the thirteen original Freedom Riders departed Washington, D.C., on May 4, 1961. Traveling aboard two separate coaches, one operated by Greyhound and the other by Trailways, the group passed with little difficulty through Virginia and North Carolina, but they encountered violent opposition upon reaching South Carolina. Two riders, Albert Bigelow, a white retired naval officer, and John Lewis, a Black seminary student who later represented Georgia in the U.S. House of Representatives, were assaulted in Rock Hill, a working-class town with a large Ku Klux Klan presence.

Map by Associated Press Newsfeatures

Though chastened by their first encounter with violence, the activists maintained their course through South Carolina, arriving on May 12 in Augusta, Georgia, where they were served courteously at both terminal lunch counters. Buoyed by their reception there, they departed for Atlanta the following morning, passing without incident through Athens, the site of a recent desegregation struggle at the University of Georgia.

If they were relieved by their experiences in Augusta and Athens, the riders were likely shocked by what awaited them in Atlanta. In “the City Too Busy to Hate,” riders were greeted by throngs of supporters, many of them students and veterans of the city’s sit-in movement. That evening, they dined at one of the city’s most popular Black-owned restaurants with Martin Luther King Jr., who commended their courage and commitment to nonviolent protest. Although his comments to the larger group remained positive, King confided to Simeon Booker, a journalist covering the journey for Ebony and Jet, that segregationists were plotting to attack the riders when they reached Birmingham, Alabama. “You will never make it through Alabama,” warned the civil rights leader.

Violent Resistance in Alabama

Events in Alabama confirmed King’s worst fears. Although riders aboard the Greyhound coach suffered no serious injuries, their bus was firebombed when a pair of flat tires forced it to pull over to the side of the road outside the city of Anniston. Riders aboard the Trailways bus were less fortunate; a mob of angry whites descended on the group when they attempted to disembark in Birmingham, seriously injuring many of the passengers. Despite their hopes of pushing forward toward Montgomery, the injuries sustained in Birmingham and the unavailability of police protection forced the original group of Freedom Riders to suspend their journey. With logistical support from the attorney general’s office in Washington, the group boarded a plane on May 15 bound for New Orleans, Louisiana, the trip’s final destination.

Only two days later, however, a second group of Freedom Riders composed of veterans of the student-led Nashville Movement in Nashville, Tennessee, volunteered to resume the protest. After securing financial support, the group departed for Birmingham, where they were arrested and detained overnight. Shortly before midnight on May 18, a police caravan led by Birmingham chief of police Eugene “Bull” Connor escorted the Nashville riders out of town and dropped them off in a remote location just over the Tennessee state line. By the following afternoon, however, the Nashville riders had arranged for a return passage to Birmingham, where they were welcomed by a second group of Nashville-based volunteers that had arrived only a few hours earlier to continue the trip to Montgomery and beyond.

Under pressure to defuse tensions in the region, U.S. attorney general Robert Kennedy meanwhile worked behind the scenes to secure police protection for the riders from Alabama governor John Patterson. Despite the governor’s commitment, however, the riders were unprotected when they entered Montgomery on May 20, 1961. Unaccompanied by police escorts, they were attacked upon their arrival at the terminal, and many riders suffered serious injuries.

Resolution

Already intense, media attention only increased in the aftermath of Montgomery’s violence, thereby forcing the Kennedy administration to take a definitive position in defense of civil rights. As a result, the administration announced on May 29, 1961, that it had instructed the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) to ban segregation in all facilities under its jurisdiction. Robert Kennedy meanwhile sought unsuccessfully to convince the Freedom Riders to suspend their journey. Refusing the attorney general’s request, the riders in Montgomery boarded a bus for Jackson, Mississippi, where they were arrested and jailed upon arrival. Freedom Rides continued throughout the rest of the summer as successive waves of protesters, now with the benefit of federal protection, headed south for Mississippi to take part in protests that were assuming historic proportions. All told, more than 300 Freedom Riders were jailed in Jackson alone. After months of delay, the ICC officially ruled segregation in interstate travel illegal on November 1, 1961.

In the days that followed, small coordinated teams of Freedom Riders fanned out across the South to test compliance with the ICC’s ruling. Bus stations in Augusta, Macon, Thomasville, and Valdosta observed the ICC regulations, but riders in Atlanta were arrested after requesting service at the whites-only lunch counter in the city’s Trailways station. Though pleased by Georgia’s overall picture of compliance, movement leaders were puzzled by the arrests in Atlanta, an otherwise progressive city that enjoyed relatively peaceful race relations.

Predictably, riders encountered stiff resistance in December 1961 when they attempted to desegregate a white waiting room in Albany, a city already teeming with racial tension. One month earlier, at the outset of the Albany Movement, student activists unaffiliated with CORE were refused service at the white lunch counter of the city’s bus station and threatened with arrest. To determine what accommodations, if any, had been made for federal law, CORE officers and fieldworkers with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee organized a high-profile Freedom Ride traveling from Atlanta to Albany by train on December 10, 1961. The arrest, upon arrival, of each of the eight riders ignited a firestorm of protest in the city’s Black community. By week’s end hundreds of demonstrators were jailed, and local leaders had invited Martin Luther King Jr. to address mass meetings at Shiloh Baptist Church and Old Mt. Zion Baptist Church, thus setting in motion a series of events later distinguished as a critical turning point in the civil rights movement. Old Mt. Zion would later house the Albany Civil Rights Movement Museum (later the Albany Civil Rights Institute), which opened in 1998.