Benny Andrews, nationally recognized as an artist, teacher, author, activist, and advocate of the arts, grew up in rural Morgan County. Although he moved to New York in 1958, his formative years in Georgia continued to inform his work. Andrews explored American life in his collages, prints, paintings, and drawings by fusing memory and imagination.

Andrews was born on November 13, 1930, in Plainview, a small farming community three miles from Madison. His mother, Viola, instilled in her ten children the importance of education, religion, and freedom of expression; his father, George, a self-taught artist, fueled their creativity with his drawings and illustrations. Although the entire family worked in the cotton fields as sharecroppers, Viola Andrews was adamant that her children attend school. Andrews’s attendance was sporadic because he went only when he wasn’t needed in the fields or when it rained.

After several years at Plainview Elementary School, Andrews walked to Madison to attend Burney Street High School, and in 1948 he was the first member of his family to graduate. A two-year scholarship awarded by the 4-H Club enabled him to enroll at Fort Valley State College (later Fort Valley State University) in Fort Valley. The only art course offered was a single class in art appreciation, which Andrews took six times. By 1950, with the end of the scholarship money and with poor grades, Andrews left school and enlisted in the U.S. Air Force. After four years of military duty, which spanned the Korean War (1950-53), Andrews was honorably discharged. He used the G.I. Bill to fund a portion of his studies at the Art Institute of Chicago in Illinois.

Development of Style

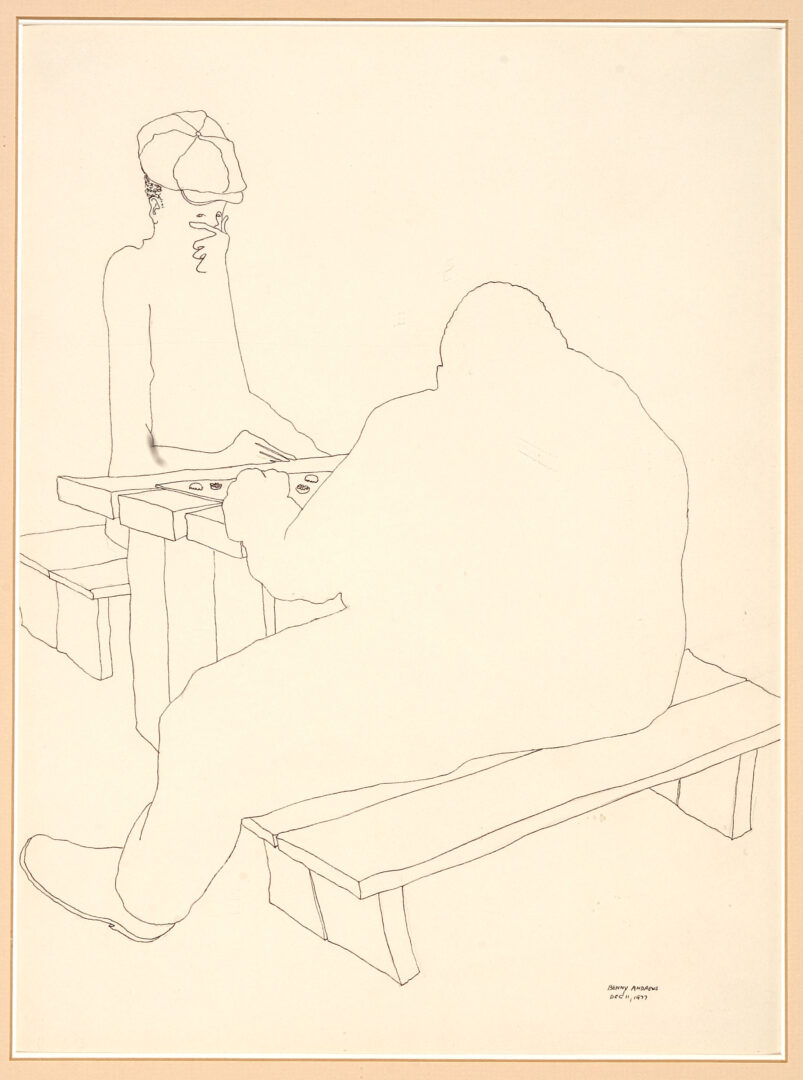

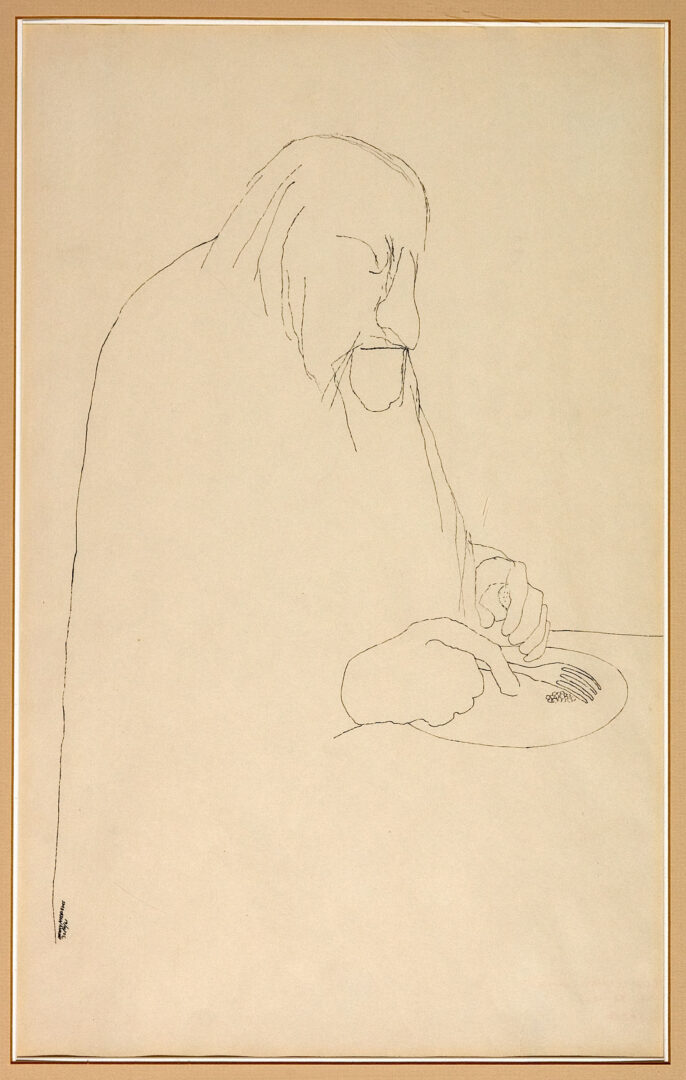

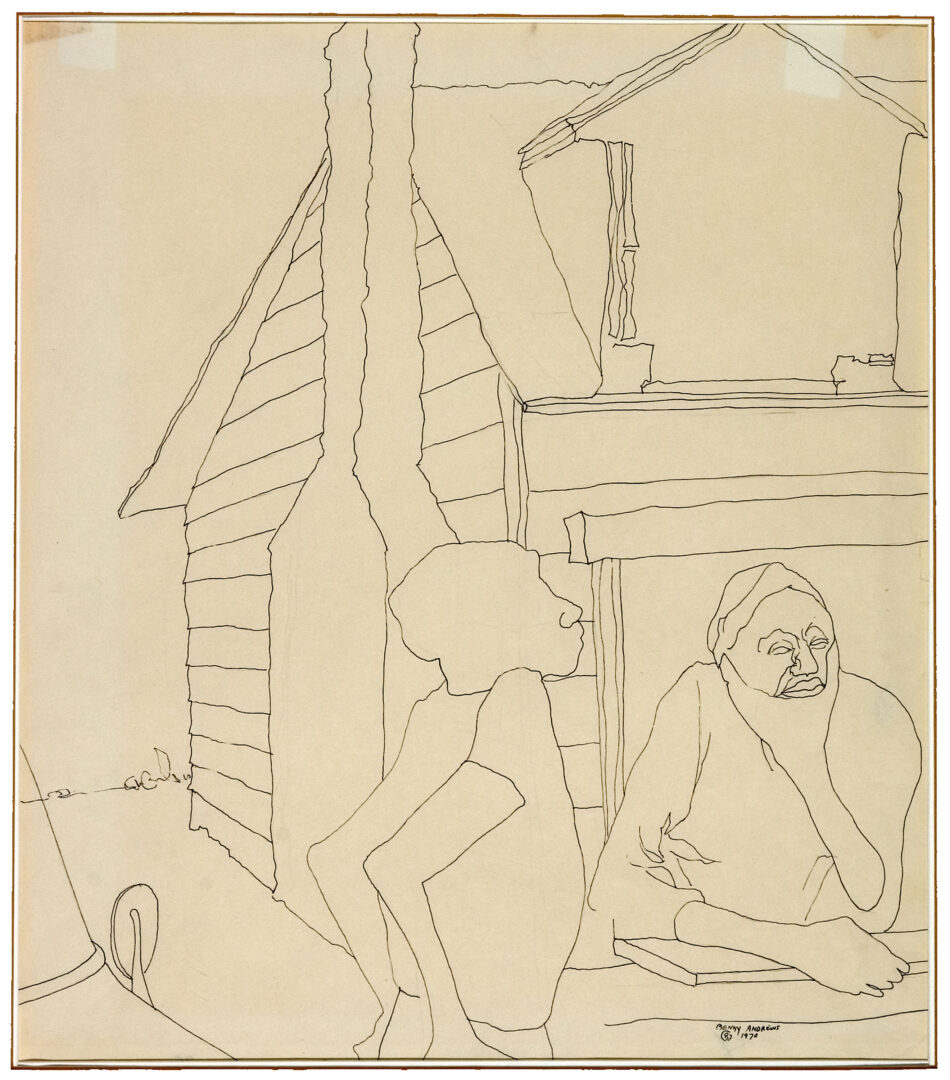

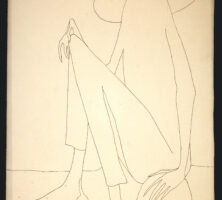

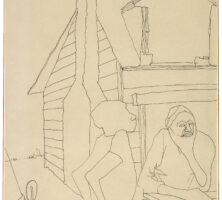

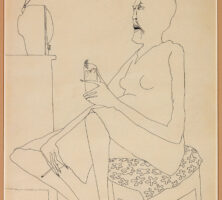

When Andrews arrived at the Art Institute of Chicago in the fall of 1954, he had never visited an art museum nor had a formal art lesson. His distinctive figurative style developed from his childhood habits. Andrews and his brother Raymond, who became a novelist, saved illustrations from newspapers, magazines, and comic books, which Andrews then copied. He created original drawings based on the observed gestures and expressions of those around him or from memories of characters he saw at the movies. With an economy of lines and elongated figures, he emphasized gesture and subtle expression.

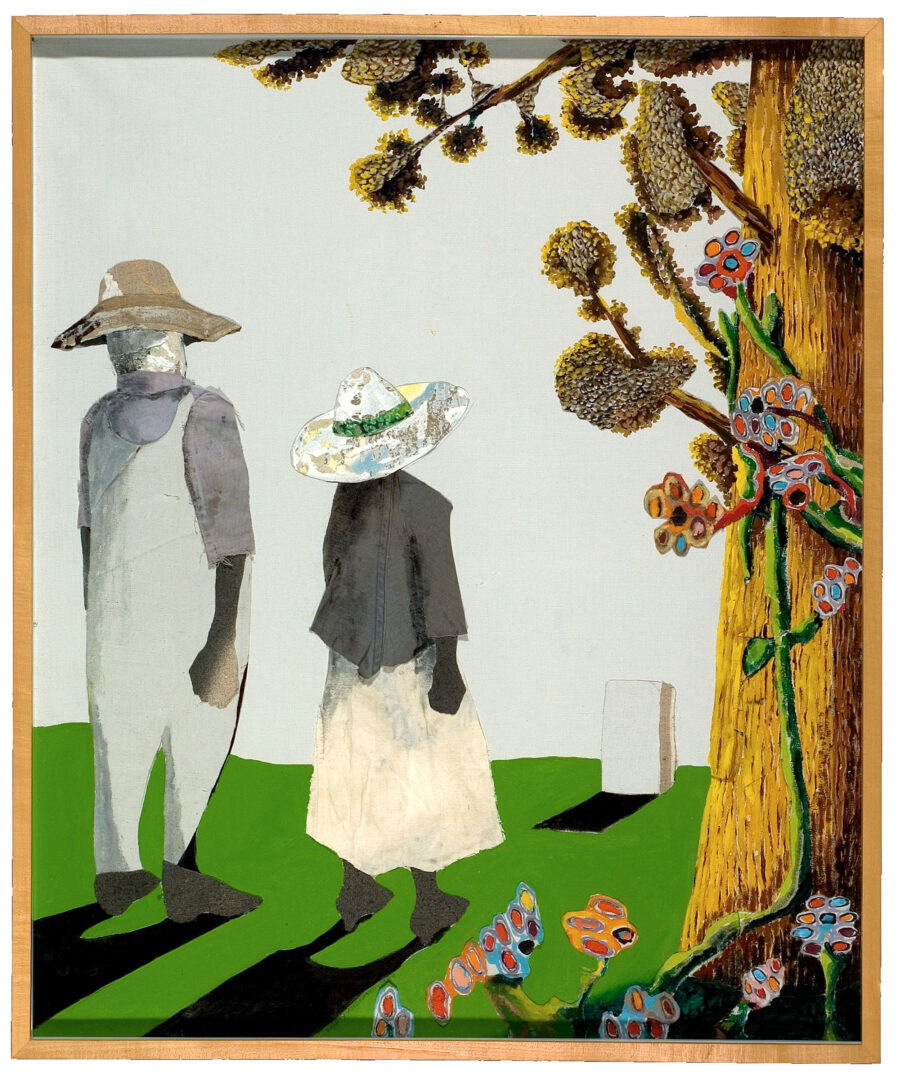

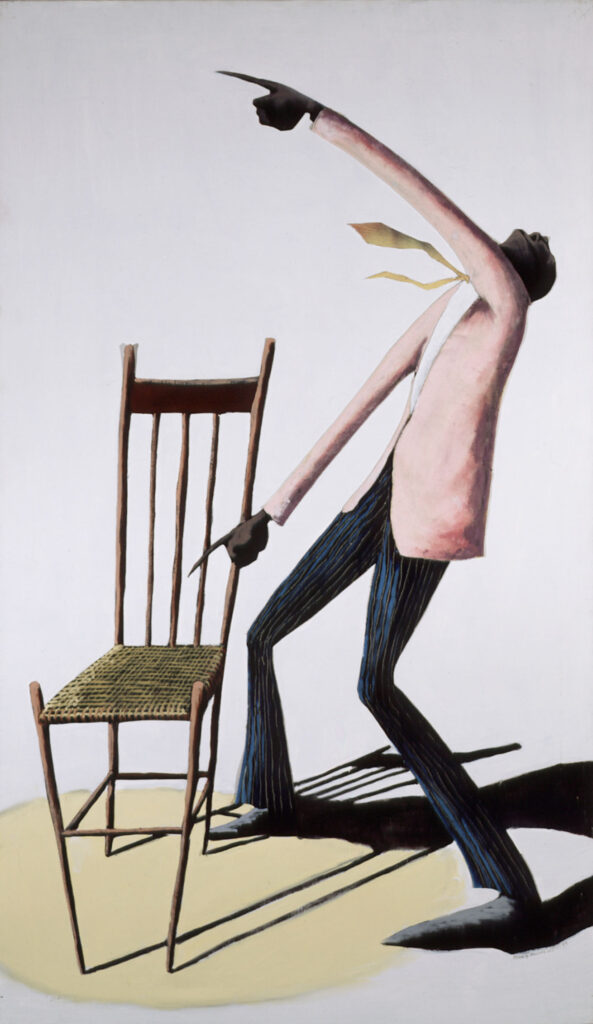

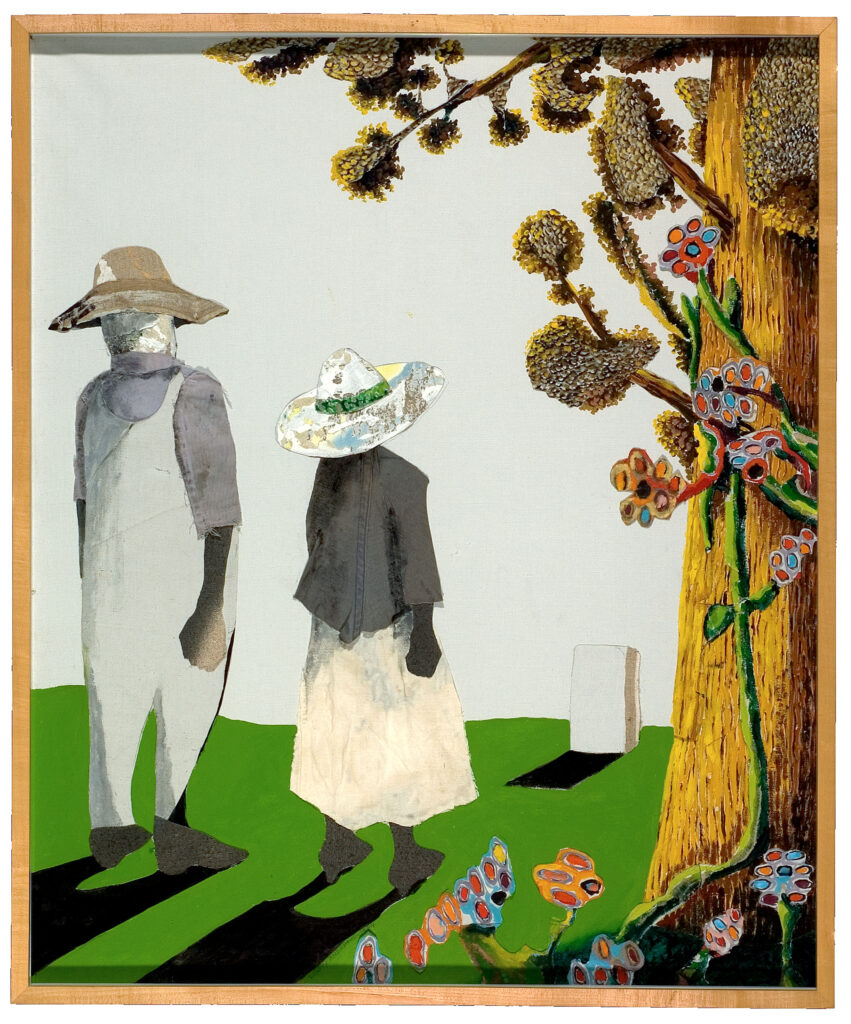

During this period Andrews experimented with collage both as a way to incorporate a three-dimensional element in a two-dimensional medium and in an effort to create rawness and tension within his work. He was inspired by artwork at the Art Institute of Chicago and by the people he saw on the streets and in the jazz clubs. His work took on a singular style, which defies categorization but shows the influences of the dominant movements of the 1950s, abstract expressionism and surrealism, as well as the dominant movements of the 1930s and early 1940s, social realism and the American Scene.

Andrews left Chicago in 1958 after he was awarded a bachelor of fine arts degree. His work had been rejected from every art show at the institute, including the veterans’ exhibition, which had a single exhibition requirement—military service. He left for New York City.

Artist, Activist, and Advocate

Within his first six years of residence in New York, Andrews became an established artist. His work was accepted for exhibition in New York; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Detroit, Michigan; and Provincetown, Massachusetts. His first solo exhibition at the Forum Gallery in New York received favorable reviews in the New York Times and other publications. He became part of the art scene, met other practicing artists, sketched people in the jazz clubs, and worked out of his studio. He also tended to his three young children while his wife worked outside of their home.

Andrews received a John Hay Whitney Fellowship in 1965 and used it to return to Georgia. His Autobiographical Series of paintings was inspired by this trip, and it established his affinity for producing several works unified by a theme. Subsequent series include Bicentennial, Women I’ve Known, Completing the Circle, Southland, America, Cruelty and Sorrows, Revival, Music, Langston Hughes, and The Migrants.

In the next decades Andrews’s artwork was exhibited nationally and internationally; he taught at Queens College of the City University of New York for twenty-nine years; and he was a visiting lecturer at many colleges and universities across the country. He became a leading spokesperson for artists whose works were not considered for exhibition in the large public institutions in New York. He was a cofounder of the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition in 1969 and led both protests and negotiations in order to bring awareness and inclusion of work by minority and women artists into major collections and exhibitions. Andrews wrote articles, curated exhibitions, and established an art program in the New York state prison system, which served as a model for other similar programs throughout the country. He and his second wife, the artist Nene Humphrey, established the Benny Andrews Foundation, which aims to introduce art to as vast and diverse an audience as possible.

Raymond Andrews’s first book, Appalachee Red, was published in 1978 and contained illustrations by Benny, who illustrated all of his brother’s subsequent novels, several other books, and children’s books, including Sky Sash So Blue by Libby Hathorn, The Hickory Chair by Lisa Rowe Fraustino, and Pictures for Miss Josie by Sandra Belton. From 1982 through 1984 Andrews served as director of the Visual Arts Program for the National Endowment for the Arts.

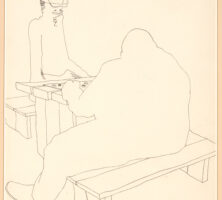

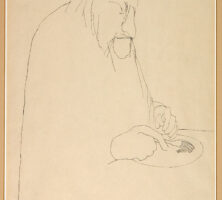

Andrews was the recipient of numerous awards and accolades, including election into the National Academy in 1997. His work is owned by more than thirty major art museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Detroit Institute of Arts in Michigan, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the High Museum of Art in Atlanta. Seven of his pieces are part of Georgia’s State Art Collection: the pen-and-ink drawings Hmmmmm, Old Woman Eating, Plower (1990), Rock (1990), Study #35 for Symbols, and The Good Life; and the mixed media oil collage Homage (1989).

Although Andrews dealt with such difficult subjects as slavery, the Holocaust, and the American response to revolt and war, his figurative expressionistic style celebrates the human spirit and the pursuit of the American Dream.

Andrews died in New York in November 2006.