Located sixty miles east of Atlanta, in Georgia’s Piedmont, Madison is the seat of Morgan County.

With a population of just 4,447 according to the 2020 U.S. census, Madison was named the number-one small town in America by Travel Holiday magazine in 2001. Although it was a center for education and agriculture in the nineteenth century, it is best known today as a popular tourist destination.

Madison was incorporated in 1809 and named in honor of U.S. president James Madison, who negotiated a treaty with nearby Creek Indians. Many of the town’s original settlers had received land grants in the region as compensation for their service during the American Revolution (1775-83). The early settlers planned their town with a geometric regularity that reflected their English background. The town prospered during the first half of the nineteenth century as a result of the cotton boom, and large plantations soon covered the surrounding landscape. By 1820 Morgan County counted 13,520 residents, almost half of whom were enslaved.

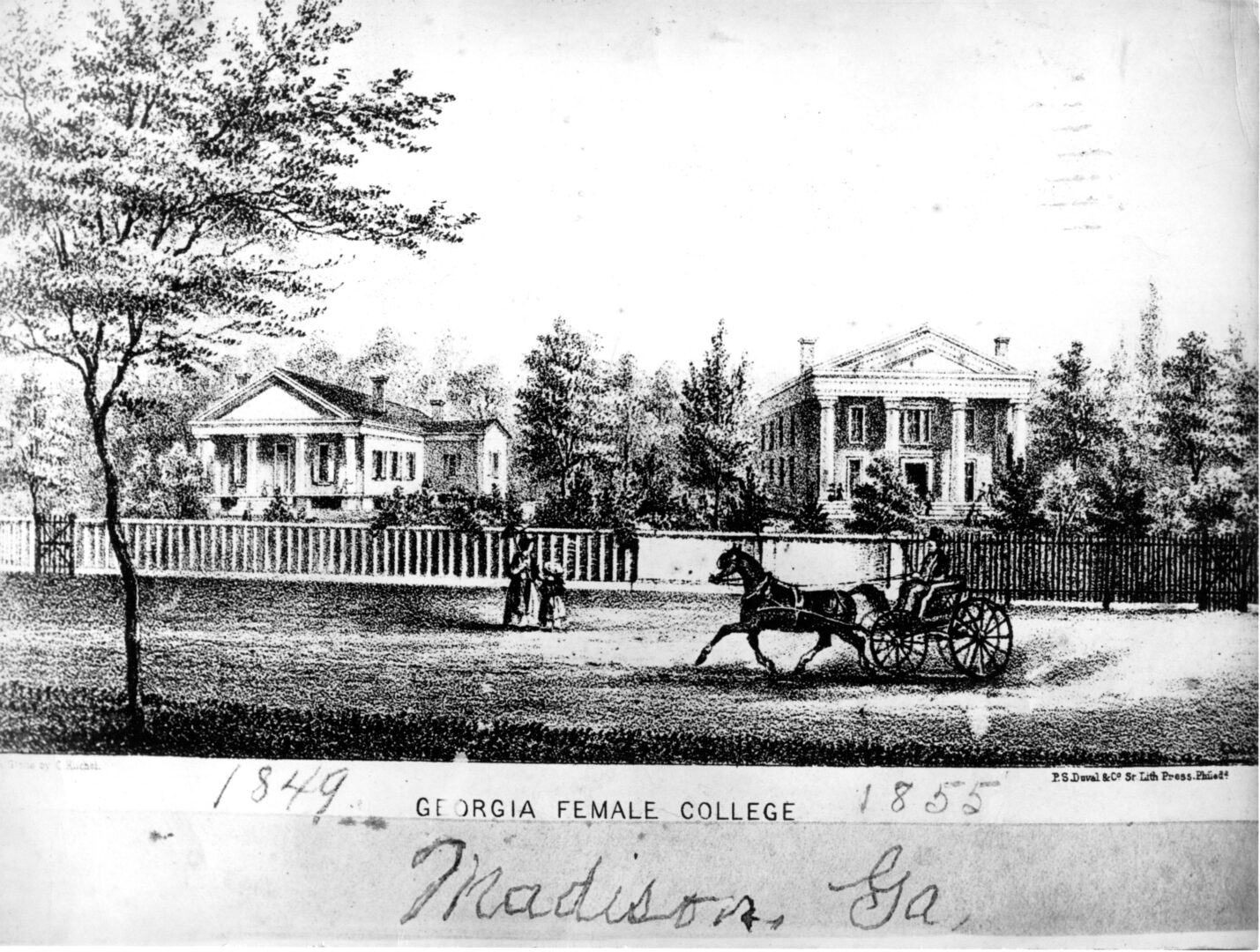

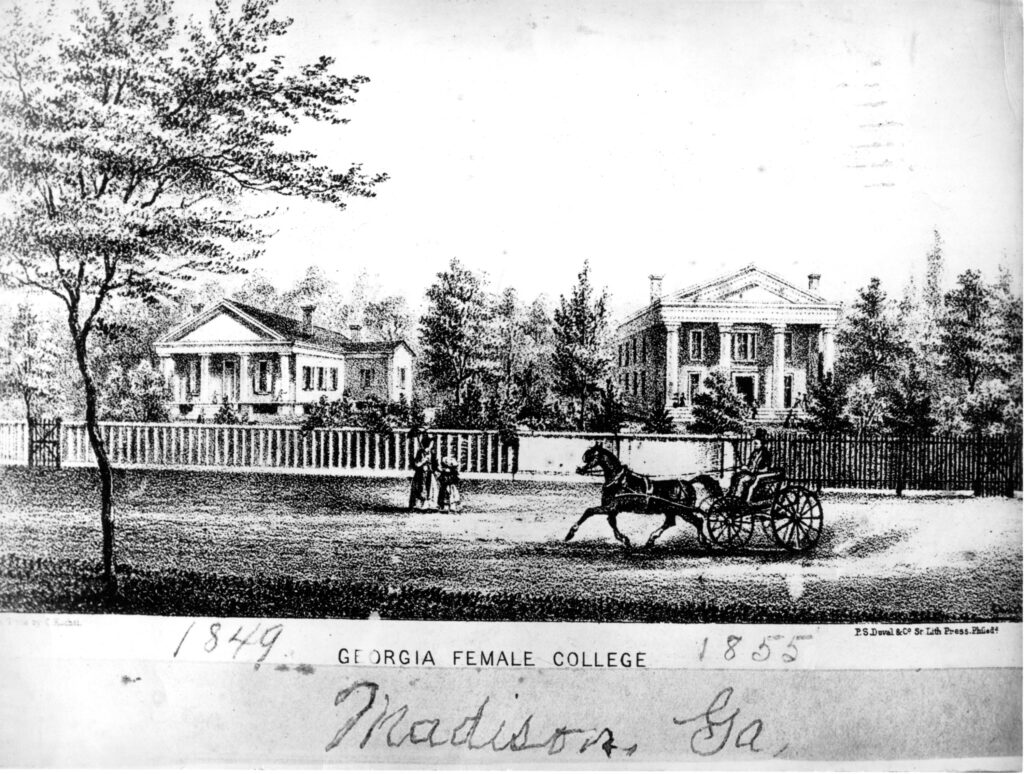

Education also played an important role in Madison before the Civil War (1861-65). Several private academies were located there, as were two colleges for women, the Madison Collegiate Institute (founded in 1849; later Georgia Female College) and the Madison Female College (1850). These schools helped to establish Madison’s reputation as a regional center of education. Rebecca Latimer Felton, the first woman to serve in the U.S. Senate, graduated from the Madison Female College in 1852, and Alexander Stephens, vice president of the Confederacy, taught at a Madison boys’ academy before beginning his political career. Notable residents of Madison in the decades prior to the Civil War include William Tappan Thompson, the southern humorist, and Lancelot Johnston, the inventor of the process for pressing oil out of cottonseed.

Joshua Hill may be the town’s most prominent resident. A U.S. congressman when the Civil War began, he resigned his position, despite opposing secession, and retreated to private life in Madison. In 1864 he reportedly convinced Union general William T. Sherman not to burn the town during his March to the Sea. The Union army did spare Madison’s center, although a number of public buildings and some surrounding plantations were burned. While accounts vary, Madison has become known in local folklore as “the town too pretty to burn.”

Although the town escaped Sherman’s flames, a fire raged through the downtown area on April 9, 1869, destroying forty-two stores and several other buildings and houses. Afterwards Madison did not regain the wealth and prominence it had possessed before the Civil War. The advent of public education in the 1870s forced the closure of many Madison private schools, and local cotton production never again equaled that of prewar years.

Madison grew some at the end of the nineteenth century, but the boll weevil crisis of the 1910s and 1920s, followed by the Great Depression of the 1930s, negatively affected Madison’s population and economy. The introduction of dairy farming helped to ease the economic downturn, but Madison would not undergo a resurgence of growth until the 1970s, when Interstate 20 was constructed just a few miles south of the town.

Well-known residents of Madison in the twentieth century included writer Philip Lee Williams and self-taught artist George Madison, known as the “Dot Man.” Madison’s sons Benny Andrews, an accomplished artist, and Raymond Andrews, an award-winning novelist, were both born and raised near Madison.

Since the construction of the interstate, Madison has become home to several large businesses, including the restaurateur Avado, the audio equipment manufacturer Denon, the paper- and building-product manufacturer Georgia-Pacific, and the lawn seed and fertilizer producer Pennington. In 1974 the Madison Historic District was placed on the National Register of Historic Places, and the town turned to tourism as its primary industry. Madison possesses several antebellum homes exemplifying various architectural styles, and other tourist attractions include the Madison-Morgan Cultural Center for the visual, performing, and decorative arts (located in the 1895 Grade School Building), the Morgan County African-American Museum, and Madison Markets, a 50,000-square-foot facility (located in an old cotton warehouse) housing shops, restaurants, and historical exhibits.