Georgia’s Black cemeteries reflect the pervasive influence of racial segregation as well as the enduring significance of African and African American cultural practices. Despite recent efforts at preservation, many remain vulnerable to the vagaries of time, and most do not enjoy the financial support afforded white burial grounds.

Enslaved People and Death

Georgia’s European and African burial grounds date to the colonial era. In the eighteenth century, the South’s rural population buried most of their dead in family plots or rural burial grounds. As attitudes about death shifted during the nineteenth century, many towns and communities created municipal cemeteries. As was typical across the nation, the dead were strictly segregated by race, class, and ethnicity.

White enslavers held considerable sway over the funeral practices and burial locations of their bondspeople. On some plantations, enslaved people were buried in a family cemetery, which held the remains of white family members as well as enslaved workers. In other instances, enslaved men, women, and children were buried separately in segregated, all-Black cemeteries housed on plantation grounds. The District Hill Cemetery in Walker County, for example, was originally part of a 2,500-acre plantation owned by James Lee and Elizabeth Gordon Lee. Only in rare cases did white enslavers provide a traditional marble grave marker for deceased enslaved people.

That is not to say that enslaved families did not commemorate or mark their loved ones’ burial sites. Inspired by African customs, enslaved peoples often held funerals and placed wooden markers, fieldstones, and household objects atop grave sites. Broken pottery and seashells often appeared on the grave sites of Black Georgians along the coastline. Another common African practice was “scraped ground maintenance,” in which the grass atop the grave was removed, leaving exposed hardened earth. Behavior Cemetery on Sapelo Island, for example, features these exposed ground gravesites.

Although death often occurred prematurely or violently in the Black community, it was often imagined as a form of freedom and liberation from the yoke of slavery and white supremacy. In many African cultures, the spirit of the deceased crossed the Atlantic and returned home. Death, then, was cause for both mourning and celebration, and Black funerals and burial grounds often reflected these concepts.

In urban spaces, African Americans were buried on a segregated basis, whether free or enslaved. Savannah’s city leaders first approved a designated site for African American remains in the eighteenth century, though evidence suggests that the Negro Burial Grounds was not in use until 1813. When the site was redeveloped to form Whitefield Square in the 1850s, African American remains were excavated and reinterred at Laurel Grove, the city’s new municipal cemetery. Carved from the former Springfield Plantation in 1850, Laurel Grove was divided into northern and southern sections, with the “colored section” occupying the cemetery’s far south end. This arrangement was typical of the late antebellum period, and plans for Atlanta’s Oakland Cemetery, also founded in 1850, were drawn to include a three-and-a-half-acre section dedicated to the burial of African Americans. Today, many of these graves are unmarked.

Segregation

Following the end of slavery, freedpeople developed their own burial grounds. This was in part a response to segregationist polices, which often prohibited the burial of ethnic minorities altogether, or relegated Black bodies to the least desirable or flood-prone sections of predominantly white cemeteries. Yet independent cemeteries were also an expression of Black identity, respectability, and community uplift.

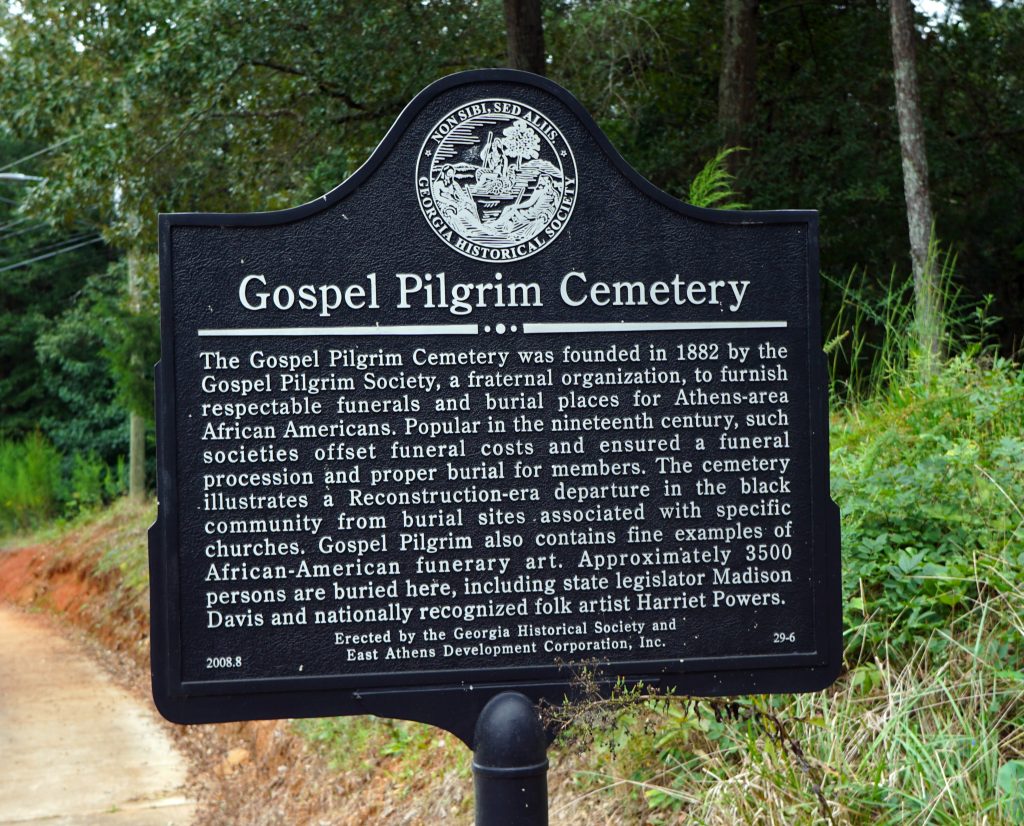

During the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, many Black cemeteries were affiliated with local Black churches, benevolent societies, or burial leagues. In Athens, formerly enslaved men and women formed the Gospel Pilgrim Society in 1879, and three years later, in 1882, the group purchased a plot of land to be used as a cemetery. The society’s official objective was “to look after and care for the sick, the indigent, and the destressed among their race,” and to ensure that the “deceased among their number, as well as all others of their race, not otherwise provided for, are properly and decently interred.” Although unaffiliated with a particular cemetery, Augusta’s Pilgrim Health and Life Insurance, organized in 1898, provided death benefits and burial insurance to its members. The goal of each of these organizations was to ensure that African Americans enjoyed access to a dignified and permanent resting place.

Much like the Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery in Athens, Atlanta’s South-View Cemetery reflects the postbellum desire for self-determination. Dissatisfied by the discriminatory treatment they encountered at the city’s existing burial grounds, South-View’s six founders—all of whom were formerly enslaved—established the cemetery in 1886 as a joint-stock holding corporation, the first of its kind in the United States. Situated amid rolling hills south of downtown, South-View is dotted by the granite and marble gravestones of prominent Black Atlantans, including religious leader Henry McNeal Turner, businessman Alonzo Herndon, and civic leader John Wesley Dobbs. But it also features more modest headstones composed of concrete aggregate as well as simple wooden crosses and fieldstone markers that reflect both the socio-economic diversity of its inhabitants and the enduring influence of vernacular funerary practices.

The civil rights movement and the dismantling of legal segregation largely eliminated the need for all-Black burial grounds as new and historic cemeteries gradually ended racial segregation. By the late 1970s and 1980s, integrated memorial cemeteries had become the norm, and Black and white Georgians were finally laid to rest together.

Preservation

With segregated burial grounds gradually falling out of favor in the late-twentieth century, fewer individuals were laid to rest in these spaces. In many cases these cemeteries no longer had living legal owners and lacked perpetual care arrangements. Often relegated to the periphery or located in impoverished sections of town, many of these sites were ignored by local government officials and failed to receive upkeep that was typically provided to white cemeteries. Plants and trees became overgrown, often obscuring gravesites and damaging historic gravestones. Some of these cemeteries were vandalized or targeted for redevelopment projects.

Many historic African American burial grounds are poorly marked, which presents unique challenges to preserve these historic and sacred sites. Indeed, the absence of stone markers, periphery fencing, or front gates makes these spaces particularly vulnerable to disruption. In the late 1960s private developers constructed homes and roadways atop graves near the St. Paul Baptist Church, a predominately Black church located in DeKalb County. More recently, in 2015, the University of Georgia disinterred the remains of approximately 105 people while expanding Baldwin Hall on the university’s North Campus. This parcel of land had initially been part of the Old Athens Cemetery and contained the remains of enslaved people who had been buried in unmarked plots.

In contrast, white cemeteries are generally well preserved and often designated as state or national historic sites. For example, the white section of the Hamilton City Cemetery, in Harris County, is maintained by Hamilton Cemetery Association, while it is unclear who owns or is responsible for the section dedicated to the burial of African Americans. Newnan’s Oak Hill Cemetery, which contains the graves of former Confederate soldiers and esteemed white citizens, has neatly manicured lawns, a garden-like atmosphere, and well-preserved gravestones. But the town’s historic Black burial ground, a wooded parcel that contains the unmarked graves of enslaved people, suffered from sustained neglect and was used as a dumping ground by city contractors as recently as 2021.

Both nationally and locally, there have been recent efforts to preserve Black cemeteries and bring awareness to the vulnerabilities of these spaces. In 2006 Athens residents established the Friends of Brooklyn Cemetery to clear brush and debris from gravesites, research its history, and learn more about those buried there. At Alta Vista Cemetery in Gainesville, city officials erected a monument in 2017 to honor the 1,100 men, women, and children buried in the historic cemetery’s segregated Black section. Despite these recent preservation efforts, many African American cemeteries across Georgia are still threatened by construction, vandalism, or the natural environment, and local communities continue to debate the future of these sacred spaces.